When children step out of their traditional elementary school classroom to learn outdoors, they experience a wide range of benefits. Outdoor learning is fun, active and fosters creativity and problem solving.

Outdoor spaces are stimulating and offer a variety of ways for children to explore different topics and pursue their own interests. Outdoor learning also teaches children to get to know and take care of their natural environment.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and local governments have recommended outdoor learning to support physical distancing and reduce viral transmission at school.

However, despite clear benefits for children and society, teachers still face many barriers when putting outdoor learning into practice.

Teachers face barriers

In our recent study in Canada elementary teachers emphasized they were highly motivated to take their students outdoors for learning on a regular basis. However, many felt alone in their approach to teaching and noted substantial barriers in the education system when planning outdoor learning for their students.

Teachers highlighted several barriers: a lack of support from the school principal; a highly structured school schedule that required students to be onsite at all times; lack of outdoor clothes for all-weather learning; parental consent procedures; a required adult-to-student ratio to leave school grounds; a lack of preparedness for teaching outdoors; and families who question the value of outdoor learning.

Overall, teachers said that school policy and mainstream parental views tend to regard outdoor learning as play time, and see it apart from “real school.”

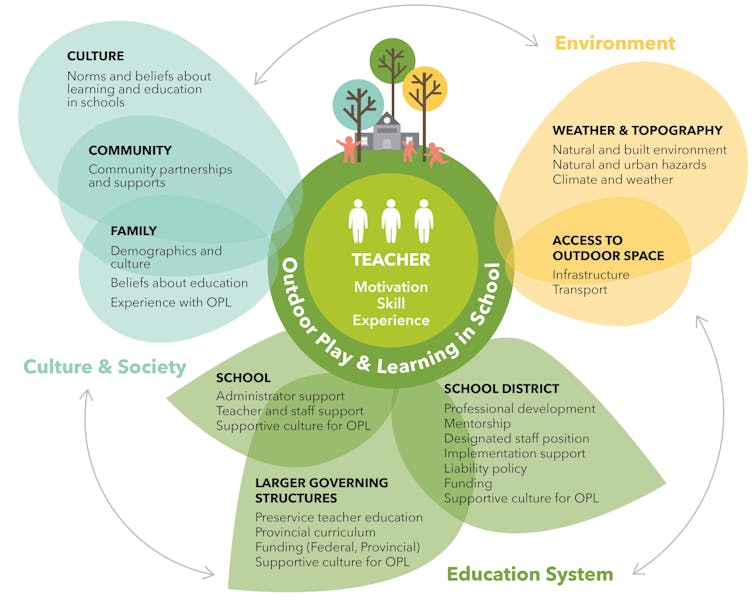

To make outdoor learning more sustainable and to integrate it into school practices, barriers need to be removed and support needs to be in place at all levels of the education system and society. Supports need to be in place at all levels — including support from the school, the school district (board), larger governing structures, as well as from families and communities — to make outdoor learning more sustainable, and to integrate it into school practices.

Some schools and school districts have taken concrete actions that successfully support educators in teaching outdoors. These actions are important as they pave the way for regular and sustainable outdoor learning in elementary schools. Here is what schools and school districts can to do to support outdoor learning:

1. Prepare teachers

Many teachers have a keen interest in outdoor learning but feel unprepared for teaching outdoors. Preparing teachers for outdoor learning includes regular professional development opportunities in schools and school districts and access to a community of educators involved in outdoor learning.

Through professional development, teachers learn how to plan lessons for outdoor learning. In a community of practitioners, teachers share experiences about outdoor learning, celebrate successes and support each other when they face problems. Experienced teachers act as mentors by sharing successful strategies and providing guidance for other teachers who are newer to leading lessons outdoors.

Ultimately, preparation for outdoor learning needs to be integrated into teacher education programs to prepare teachers early in their careers when they are beginning to develop and refine their teaching routines.

2. Simplify guardian consent

The requirement to obtain separate guardian consent for each outdoor learning trip makes spontaneous trips outdoors unfeasible. Several school districts now accept year-long consent forms in which guardians can consent for their children to participate in neighbourhood walks at any given time during the school year.

Standing consent for outdoor activities in the neighbourhood is key so that teachers can plan outdoor learning freely during the school year.

3. Open gear-lending libraries in schools

Many children arrive at school in clothes that aren’t appropriate for outdoor learning. Schools can establish gear lending libraries where they collect donated outdoor gear (like rubber boots, rain coats) and buy necessary gear with funds allocated to support outdoor learning. Providing all children with weather-appropriate gear provides financial relief for individual families and supports equity in access to outdoor learning.

4. Include support teachers

School policies mandate that specific adult-to-child ratios are met when teachers leave school grounds with their students. Ratios vary depending on children’s ages and needs. Where families face few socio-economic barriers in being connected with the school and attending school activities — for example, where parents or guardians speak English and have flexible schedules — teachers can often rely on adult family members to volunteer as supervising adults for outdoor learning. However, expecting children’s families to participate means inequitable access to outdoor learning.

This challenge can be addressed by having a designated role for resource and support staff in schools to support outdoor learning.

5. Allocate funding

School districts need to allocate funding for outdoor learning. This includes providing resources for: a district specialist for outdoor learning who can mentor and prepare other teachers or help with grant applications; “loose parts” materials that can be combined or used alone in open-ended and creative play like large blocks, pots, stackable cups, planks of wood; other materials or gear, such as for gardening or a gear-lending library; transit, if high-quality outdoor spaces aren’t accessible by foot.

Reliable funding is essential for creating sustainable outdoor learning practices in schools.

6. Advocate for outdoor learning

Many adults have no experience with outdoor learning. A common view of learning is that it takes place in an indoor and classroom-based setting. It’s important that educators, families and children who witness the successes of outdoor learning share their experiences and advocate for more.

Educating the public about outdoor learning changes public perception of what learning looks like in schools, and creates buy-in among families, educators and other stakeholders.

The growing interest in outdoor learning over the past years is promising. Some schools have questioned the traditional indoor classroom as a best format for teaching and learning and developed a school culture that prioritizes outdoor learning as a method of teaching.

From a societal perspective, systematic integration of outdoor learning into school practices is an effective way to reduce inequities in children’s access to the outdoors. While barriers to outdoor learning still exist in the larger education system, school districts have the opportunity to pave the way for outdoor learning and scale it up.

This article has been Co-authored by , and . The article originally appeared in The Conversation.