LIVING MEMORY

Beyond Stardom: Om Puri and the Art of Acting

Even though Om Puri passed away, his superb acting, his spirited work and his contribution to the making of good cinema will continue to inspire us.

Prof. Avijit Pathak teaches Sociology at JNU, New Delhi

Art transcends the artist. An artist dies; the embodied existence , because of its very nature, withers away. However, what remains is the soul of art. And to invoke an artist is to have a sensitivity to engage with his art, his creation—not just the ‘personality’ of the artist. It is in this context that I intend to walk with Om Puri, try to understand the spirit of his work, and reflect on cinema as an art form, its ideological tone, and the role of an artist in its dissemination and popularization.

(I)

Art, Politics and Meaningful Cinema

There are two things that need to be stated at the very outset. First, to speak of an artist in the field of cinema is not a very easy proposition. The very nature of cinema as a medium poses some challenges. Its distinctively visual character, its spectacular nature often constructed by technology and its commercial logic to stimulate the mass psychology of entertainment often generate a phenomenon called ‘stardom’. As ‘superstars’ and ‘mega stars’ (as far as our cinema—primarily Hindi films—is concerned we are so comfortably used to this vocabulary) dominate , the delicate art of acting tends to suffer. The externality of ‘stars’—look, glamour, distinctive markers of ‘style’, seek to devalue what a good artist needs—the fineness of acting or the ability to dissolve into the character. Beauty queens become heroines; ‘megastars’ assure box office success; art is sacrificed amidst sensational spectacles. Well, this is not to suggest that all ‘stars’ are bad actors or poor artists.

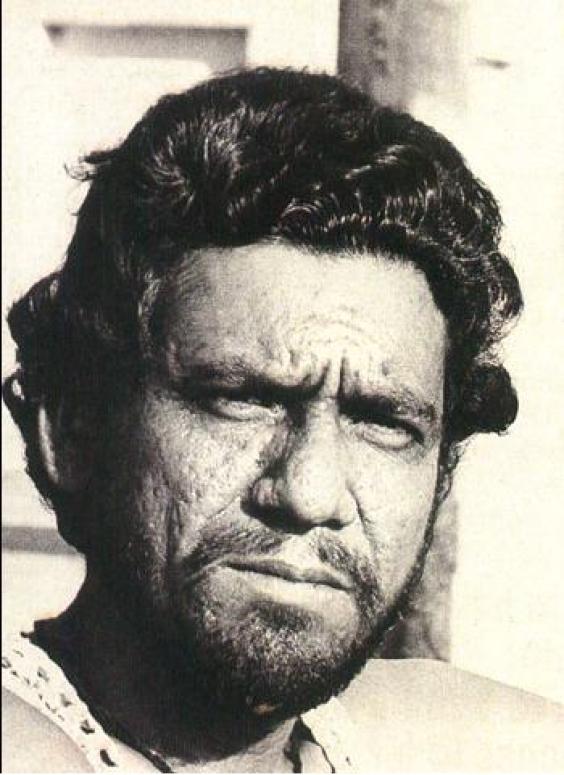

To take a couple of illustrations, Rajesh Khanna, despite his ‘superstar’ status, was remarkably good in Hrisikesh Mukherjee’s Anand—a film in which his love and laughter, pain and tears, and above all art of dying gave a new meaning to cancer as a disease; or, for that matter, Amitabh Bachchan in Prakash Mehera’s Deewar was not merely a ‘megastar’; he was an actor portraying intense emotions and psychic turmoil of a misdirected /angry young man in a corrupt/violent world; and even Sarookh Khan in Ashutosh Gorwinker’s Swadesh could come out of the baggage of ‘King Khan’, and merge with the role of a scientist trying to come to terms with the harsh Indian reality. However, what cannot be denied is that more often than not ‘stardom’ kills the spirit of acting. Under these circumstances, to refer to Om Puri is to engage in an act of dissent because he defied this culture of ‘stardom’. He didn’t look like a ‘hero’ (his poxmarked face was so different from the ‘cuteness’ of Ranvir Kapoor; his gestures were not that of ‘polished’ Amir Khan or ‘easy going’ Salman Khan); he didn’t perform any magic that Rajnikant does on the screen. Yet, with the sheer power of his acting and his hard work and commitment to art he conquered our minds. He made us believe that art is more important than stardom. Second, to invoke Om Puri is to rethink cinema. True, art and entertainment, or art and commerce need not necessarily be always contradictory. However, to reduce cinema into a mere commercial venture with gross entertainment is to devalue the art and aesthetics of cinema. How often the Fara Khans and Karan Jawahars of the world do it! Furthermore, like great literature meaningful cinema is also a social text, a worldview, a way of seeing politics, culture and ethics. Well, at one level all films are political; with the proliferation of ‘cinema study’ we see politics everywhere—the Nehruvian era of nation-making in the films of Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor, the rise of Indira Gandhi, Emergency and the turbulent 1970s, and the rise of Amitabh Bachchan, terrorism and nationalism in Mani Ratnam’a films, and the neo-liberal market, globalization and the dynamics of Indian diaspora in the glossy films of the last two decades. No, I am not talking about politics and cinema at that level. I am talking about a more serious engagement between cinema and social commentary. At the same time, I am not saying that art is a political manifesto or a slogan or a sociological thesis; we often feel tempted to trap into this reductionism—‘bourgeois’ art/ ’working class’ art, ‘progressive’ art/ ‘decadent’ art. If art loses its aesthetics, its fineness, its nuanced expression, it cannot be regarded as meaningful, even if it is ‘politically correct’. And when good art is reconciled with a penetrating social text we find good cinema. And there are many layers of this kind of cinema: from Raj Kapoor’s Awara to Hrisikesh Mukherjee’s Nemok Haram , from Mrinal Sen’s Chorus to Shyam Benegal’s Manthan. It is in this context that we can say that Om Puri was truly lucky to find directors like Satyajti Ray and Govind Nihalini , work with them and take part in some remarkably good/meaningful films. His superb performance in some of these films arouses our hope in the art of acting and the craft of making good cinema.

(II)

From Dukhi to Inspector Anant Velankar: Om Puri’s Social Realism

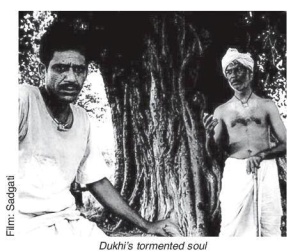

The convergence of Munshi Premchand and Satyajit Ray (Premchand’s story, Ray’s direction) and the acting of Om Puri gave us Sadgati—a 1981 film, a short film initially made for television. It was a film that reminded us once again of the process of dehumanization implicit in the practice of caste hierarchy, social exclusion , stigma and untouchability.

Premchand’s story was superb; but when we transformed ourselves from readers to viewers, the experience was equally powerful. True, Ray was a master film maker; the tightness of the script (less words, but more the visual narration; see how the camera captured a flabby/lazy Brahmin pandit having a nap after a heavy mill, whereas the untouchable labour with an empty stomach desperately searching a smoke, and being reminded of his social location by the oppressive gaze of the Brahmin’s third wife) and the realism of the setting took the film to a great height. But it was Om Puri as Dukhi—a chamar, a victim of the caste-ridden Hindu society, a struggling man with an empty stomach and feverish body trying to persuade the local Brahmin pandit/priest to come to his hut to fix up the auspicious date of his daughter’s marriage, a man repeatedly humiliated and compelled to do (all sorts of work in the Brahmin’s household, and eventually chopping a huge log of wood) what his weak body could not bear—who, as every lover of good cinema would concede, made Ray’s task easier. There was no separate identity of Om Puri—a graduate of the Pune film institute; he became Dukhi; he was inseparable from the character. Look at his bodily movements, his facial expression, the expression of his anguish, his helplessness, his ultimate stubbornness (when the Brahmin rebuked him for not succeeding in chopping the log of wood) in the movement of his hands with the axe, and eventually his death. Premchand’s words were translated so well into the idiom of cinematic performance.

From the caste-ridden rural India as we come to a modern city with its criminalization of politics and the bankruptcy of the state machineries like the police force, we see yet another brilliant film—Govind Nihalini’s Ardh Satya – a film(1983) in which Om Puri revealed his talent once again. This time Om Puri’s merger with the character of Anant Velankar—a police inspector , despite his good will to punish the guilty, realizing his limitations, his insignificance before the powerful criminal-politician nexus, his turmoil, ethical dilemma, his decay, violence and revenge helped Vijay Tendulkar’s powerful script and Nihalini’s focused direction to take Ardh Satya to a great height. See the way the character of Anant Velankar unfolded itself. He saw his oppressive father beating up his mother; as he joined the police force he saw the system from within—its rot, its helplessness before the corrupt and the powerful; he found Rama Shetty—the embodiment of the system, a criminal politician (acted by yet another brilliant actor Sadasiva); he saw his inability to do anything about it, his increasing frustration, his alcoholism, his misdirected violence as an expression of hidden anger (in the police lock up he started beating up a simple thief leading to his death), his suspension, and eventually his final encounter with Rama Shetty. Once again Om Puri acted through every element of his being. His face could reveal the psychic turmoil he was passing through ( and Nihalini’s camera could capture the movement of bones and muscles of his anguished/passionate face); and his every meeting with Jyotsna Gokhale (Smita patil)—a college lecturer with deep humanism and literary sensibilities would reveal his longing, his search for another world. Smita Patel as jyotsna was absolutely brilliant; her every gesture, every movement would indicate her grace, her empathy, her concern for the tormented soul of Anant Velankar. Possibly in the harsh/brutal world of criminal-politician nexus, the feminine grace of Jyotsna Gokhale was the ultimate refuge and conscience for Velankar. Feel the moment of surrender: Om Puri as Anant Velankar confessing before Smita Patel as Jyotsna Gokhale: ‘I haven’t done anything which makes me proud…I will have to win over my weakness.’ As a realistic film it doesn’t end with the glorious victory of the ‘heroic’ police officer; instead, it is a story of defeat and turmoil, helplessness and moral decay, lost ‘masculinity’ and revenge, near and far, love and pain (not glossy romance; the communication between Om Puri and Smita patel was so different from what these days we see in Aditya Chopra’s films). In a way, throughout the film Om Puri revealed the trap of this chakravyuh :

Balancing impotence with manhood

the needle of this perfect balance

points us towards a half-truth.

Om Puri is no more. But his art will continue to enchant us, and inspire us to strive for good/meaningful cinema. And that is precisely our homage to a great actor.

This article is published in The New Leam, FEBRUARY 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.20) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.