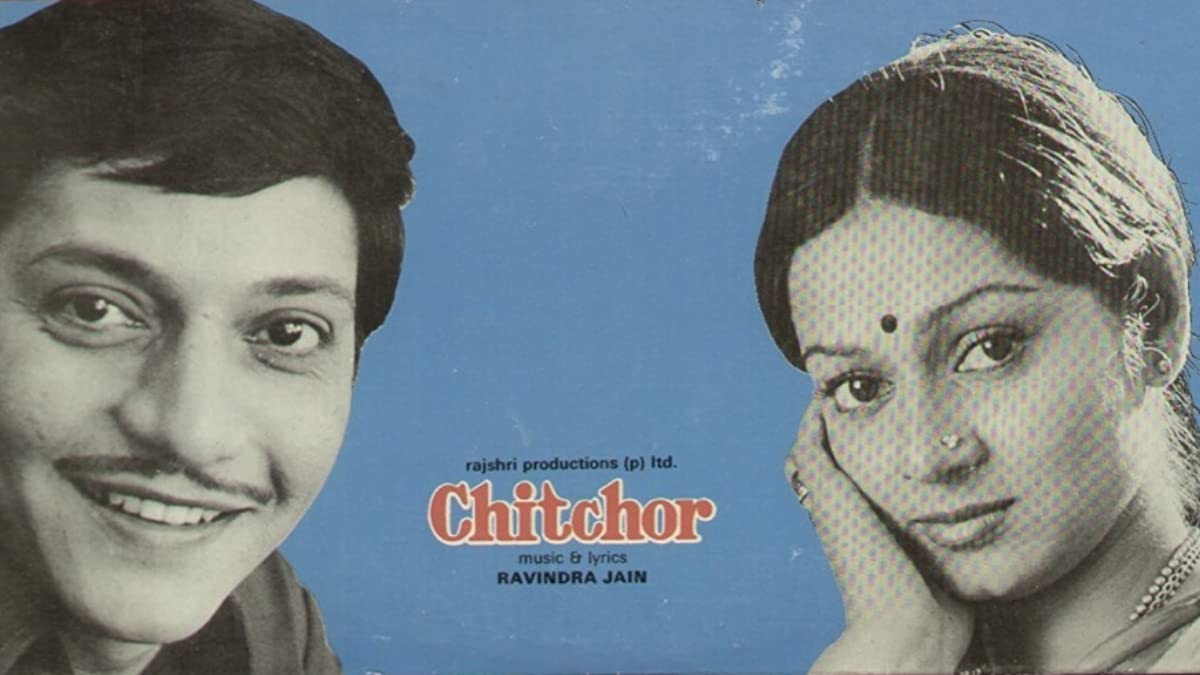

It was June 3, 2020. I watched Chitchor (thanks to You Tube). Well, for the first time I saw this film when I was in college. But then, it is difficult to forget Basu Chatterjee’s films. At this time of pandemic-induced psychic nausea, I felt like celebrating Chitchor once again. Possibly, I was striving for the music of life—its grace and simplicity, or its beauty in what otherwise appears to be ‘ordinary’. But then, see the inexplicable mystery of existence. The next day—June 4—I came to know about Basu Chatterjee’s final journey: the phenomenal body withering away, and his soul merging with the infinite. As an ordinary mortal, I felt sad. Yet, even amid this sadness, I could continue to see him alive in his creations. In fact, some of the extraordinary visuals from his films began to fill my consciousness with sublime softness, joy and human warmth. I saw Amol Palekar, Vidya Sinha and Zarina Wahab ; and the melody of Rajnigandha Phool Tumhare enabled me to experience the prayers of love and longing.

A lyrical story-teller

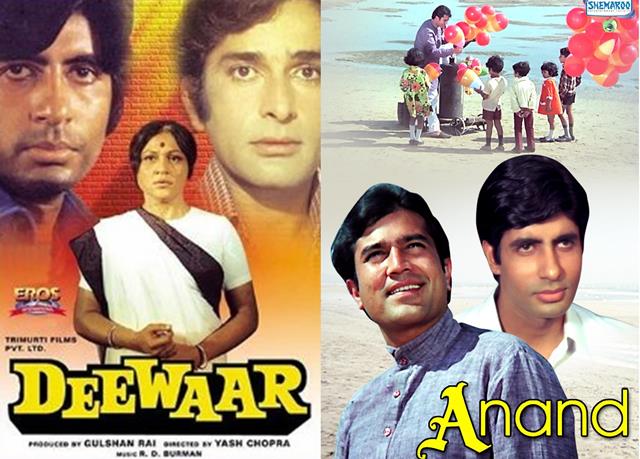

What sort of a filmmaker was Basu Chatterjee? I am neither a film historian nor a film critic. But I love cinema. And I see cinema not necessarily as a Ph.D thesis—a socio-political text. I feel its colour and beauty; I try to experience the art of story- telling; I am not indifferent to songs, dreams and even the realm of the ‘unreal’. In a way, I do not carry the burden of the ‘intellect’ as I watch films; my reason as well as my heart, or my aesthetic longing as well as my enthusiastic eyes that love to see the play of the camera remain alive. Yes, I have seen all sorts of films. Take, for instance, the state of Bollywood in the 1970s. Yes, I know that Amitabh Bachchan was the ultimate star. His intense anger, deep pain, psychic wound and search for redemption made him immensely popular; and directors like Yash Chopra, Prakash Mehra and Manmohan Desi could tap his potential. He was an actor as well as a star. And we grew up with the Bollywood blockbusters like Zanjeer, Deewaar and Sholay. And then, there was yet another experiment; and we saw the directors like Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalini coming forward with the films characterized by harsh social realism. Unlike the typical ‘commercial films’ (with their glitz, glamour and stardom), the films like Ankur, Manthan and Aakrosh sought to create new sensibilities. Beyond dance and music, or car race and fight: there was politics, the reality of societal conflict and violence, the story of humiliation and exploitation, and the possibility of a new language of resistance. And these ‘art’ films sought to awaken us; and we became familiar with the likes of Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi.

Melodrama vs. realism; mythical heroism vs. everyday struggle; and mass entertainment vs. seriousness: the viewers began to look at our cinema through these dualities. Yet, we were lucky; we could see yet another possibility—beyond the stereotypes of ‘art’ and ‘commercial’ cinema. Well, Bimal Roy was a pioneering figure; so was Hrishikesh Mukherjee. Possibly, Basu Chatterjee retained this legacy: the art of making the kind of films that, far from alienating ‘non-intellectual’ viewers, would invite them, and take them to a world where simplicity has not withered away, ordinariness is not devoid of laughter and humour, or joy and beauty, and struggles have not succeeded in deserting the human mind. No wonder, Sholay or Deewaar could not diminish the popularity of Rajnigandha or Chhoti Si Baat; nor could Amitabh Bachchan deprive us of the affinity we felt with Amol Palekar. Well, we admired Naseeruddin Shah; but Amol Palekar’s shyness was no less intimate. And beyond the ‘glmorous’ Zeenat Aman and ‘subaltern’ Smita Patil—there was Vidya Sinha. And people like us who were neither rich nor subaltern could find no difficulty to walk with Amol Palekar or wait with Vidya Sinha at a bus stop in Mumbai, and identify with her inner world through Lata Mangeshkar’s heart-touching song:

Na Jaane Kyon—Hota Hai Yeh Zindegi Ke Saath

Achaanak Yeh Mann, Kisike Jaane Ke Baat

Kare Phir Uski Yaad Chhoti Chooti Si Baat

Na Janne Kyun

Let film historians or critics write research papers and debate whether Basu Chatterjee was an ‘intellectual’ or an ‘art’ filmmaker. But I have no hesitation in saying that Chatterjee was a lyrical story-teller; his films were soft and sensitive; and he aroused our positive emotions. He worked with the likes of Salil Chaudhury and K K Mahajan, and enabled Yesudas or Lata Mangeshkar to sing some of the finest songs. Sometimes, I feel that there is inherent goodness when a song like Na Bole Tum Maine Kuch Kaha (from the film Baton Baton Mein) enters the interiority of our existence.

Simplicity—the beauty of being ordinary

In this context there are two distinctive features of his cinema that I wish to reflect on. First, in his films I see the beauty of being ordinary—the tales of human weakness and vulnerability, timidity and shyness, and yet the innocence and poetry of love. Take, for instance, the character of Arun Pradeep (Amol Palekar) in Chhoti Si Baat. There is no ‘heroism’ in his deeds; there is no glamour in his life. In a huge city like Mumbai he is just one of those thousands of ordinary people who come to the bus stop, reach their offices, work, meet their bosses with fear and apprehension, and merge with the flowing crowd. Moreover, Arun is not ‘smart’; he is shy and hesitant. But then, he is not cynical; he is not crippled from inside. He loves Prabha Narayan (Vidya Sinha). He ‘follows’ her, sees her from a ‘safe distance’, passes through intense psychic turmoil as both of them happen to wait in the same bus stop, and take the same bus. He imagines that he would talk to Prabha and reveal his love. But then, he is not like the ‘hero’ of the typical Bollywood blockbuster. He is ordinary; he is not yet very sure of himself. And as he sees Naresh Shastri (Asrani)—Prabha’s colleage, he feels more and more insecure. Naresh is street smart. He is egotistic and ‘confident’. He is ‘easy’ with Prabha.

However, Arun finds Colnel Julius Nagendranath Wilferd Singh (Ashok Kumar): the man with a missionary zeal trying to arouse self confidence amongst those who feel shy and hesitant to articulate their love. Here Chatterjee brings the element of comedy. And we see how the Colnel begins to mould Arun into a more mature and confident young man through a set of personality development techniques. And eventually, Arun comes back; he is now assertive, sure of himself; it is no longer easy to fool him; and even Naresh Shastri is surprised. Arun has finally found his Prabha.

Second, in Chatterjee’s films I see the grace of tenderness. There is nothing loud and noisy. Even though there are struggles, middle class aspirations, ambiguities and dilemmas, the therapeutic power of love and understanding characterizes Chatterjee’s aesthetics. Recall Chitchor. Feel the simplicity of Geeta (Zarina Wahab): her rhythmic walk and innocence merge with the silence and natural beauty of Madhupr. Yes, she is growing up; her parents are concerned about her marriage. And then, their older daughter Meera who lives in Mumbai informs them of the arrival of an engineer (who can be a possible match for Geeta) at Madhupur. Yes, Vinod (Amol Palekar) arrived; and Geeta’s parents felt happy; they loved him; and cherished the idea of Geeta and Arun coming closer. Arun and Geeta singing together Tu Jo Mere Sur Mein Sur Mila Le : what a tender moment. It is soft and sublime. It enchants the soul.

But then, it is in the very rhythm of life that we pass through a puzzling turning point. Here is yet another letter from Meera. The engineer has not yet arrived; he would arrive soon. In fact, Arun is the overseer. It shocks, confuses and surprises Geeta’s parents. Eventually, Sunil (Vijayendra Ghatge)—the real engineer—arrived. And Geeta’s parents asked her not to mix with Arun, and marry Sunil. Geeta’s pain and psychic turmoil, and Sunil’s decision to marry her: this ‘defeat’ of the overseer, or the ‘success’ of the engineer takes us to the complex domain of masculinity, success, patriarchy and marriage. But then, Basu Chatterjee was not an overtly politico-feminist filmmaker. With his tender touch and faith in human possibilities, he gave a new turn to the film. Even though Arun with his disheartened soul planned to leave Madhupur, Geeta—despite her simplicity—regained her agency, and decided to make her own choice. Sunil too understood. And Chitchor ended with the union of Geeta and Arun. In the simple rhythm of life we found the possibility of justice.

Epilogue

We are passing through terribly dark times. With hyper-masculine aggression and violence, cunningness and instrumental actions, and death and pandemic, life seems to have lost its meaning, beauty and grace. Yet, even at this moment of despair, I refuse to give up my longing for what Basu Chatterjee portrayed through his cinematic creations: the musical tales of love, simplicity and human goodness. I see Madhupr, feel the vibrations of its trees, imagine Chatterjee with his camera, and Yesudas enchanting my soul through his song Gori Tera Gaon Bada Pyara…

Avijit Pathak is Professor of Sociology at JNU.