Covid-19 has led to a disruption of the material conditions of our existence. The way we produce, distribute and exchange our necessities as well as our luxuries, has been disrupted. How we keep ourselves physically secure and safe, the conditions in which we meet our friends and students, all have been shaken up. Without falling into any kind of material determinism, one can still say that this present era has seen a severe shock to the very foundations of our social life. Whether this will be a temporary shock and everything will go on as usual after a vaccine is released or whether this will lead to deep-rooted changes, it is too early to say. Whatever be the changes that might ensue in the coming years, I shall focus here only on some challenges for higher education that will carry on from older times. They are old problems, but they are taking up new forms in this Covid-19 era.

I shall talk here about the challenges posed by two key sociological processes – (1) the rationalisation and bureaucratisation of education and (2) social inequality and education’s ways of dealing with it. These are old processes but are getting a new expression today. Rationalisation and social inequality, as all sociologists know, are among the central questions of our times. Considering them will help to understand at least some dimensions of our present situation.

Bureaucratisation and Rationalisation

The rationalisation of all institutions is a worldwide phenomenon. Educational institutions have been bureaucratised and rationalised, too. In India we have had a patchy and uneven experience of rationalisation. Satish Saberwal (1995, 1996) writing in the 1980s and 1990s pointed out that we are still learning to build rationalised institutions, viz. institutions which have a clear goal and are able to reflexively orient themselves towards that goal. Saberwal was sharply attacked for this, but what he was saying was right. We have an Indian pattern of rationalisation where a large number of institutions are governed and function in a way that instead of fulfilling their social purposes actually benefits only their functionaries and their institutional power. There are notable exceptions, of course, but most schools and colleges exist without much of a reference to the goals of education for our society. They exist to give degrees and create an appearance of being superior to others. They fail to create reflective citizens, they do not foster any love for the subjects being taught by them. The transformation of the self and learning to be an active human being is mostly incidental to their functioning.

Rationalisation of institutions is about creating processes and systems that meet a particular purpose. But most institutions of higher education in India are not clear about what their major purpose is. Students memorise textbooks and teachers give lectures without significantly reflecting on what they are doing and why. Key social goals do not form the trajectories of higher education, instead the latter respond largely to the opportunism of power. While there are notable exceptions, we have been characterised by the pursuit of symbols of excellence rather than the pursuit of processes that define and build excellence. Performativity and the appearance of success takes up far more attention than thinking through what excellence is and getting a clear idea of what leads to it. It is rare to see administrators and teachers critically examining the ways of teaching which can lead to excellence. As a result the growth of departments occurs because they offer status and power, rather than due to an inquiry into their significance for the growth of knowledge or of service to the people. Thus new departments of Economics get opened while Sociology and Philosophy get cut down. Teaching is about finishing a certain number of lectures and getting a degree, rather than about helping students to discover meaning and excitement in what they are learning. The pathologies of an education system that focuses only on delivering degrees are well known. Students mostly do not join because they are inspired to learn, but because they feel compelled to get degrees if they want to go up in the stratification system. Those who build institutions too focus mainly on degrees or credentials and what they mean in a job market rather than upon what that knowledge actually means and what its significance for the well-being of our country is. Many of the problems we see today related to Covid-19 are only a further expansion of that basic pattern of unreflective bureaucratisation of learning.

We have seen a seamless transition in most institutions from dull meaningless lectures into even more dull and meaningless online teaching. There are many jokes floating around on the internet created by students. Teachers are either a faceless voice speaking from headphones or if you are one of the lucky few with broadband internet then teachers are a boring head talking in a monotonous way. Institutions have little concern about the meaning of this experience or about what students think about the knowledge being given to them. In Indian bureaucracies what is important is that the rituals of the institution be carried on. The meaning of these rituals is not for us to understand.

The basic analysis of rationalisation and bureaucratisation of knowledge, as we all know, was spelt out by Max Weber (cf. extracts in Madan 2014) over a century ago. He argued that rationalisation had gradually grown over the centuries because it led to more efficient and effective institutions. Rationalisation in itself was not a bad thing. When we began to ask what the purpose of an institution was then we could change the way people worked so that they were in line with the institution’s purposes. Rationality was not just a mental process but an institutional one, whereby greater coherence and consistency was created. Modernity was characterised by the rationalisation of all institutions and as a result they consolidated far greater power in themselves than previous institutions had been able to. The institutional form that characterised modernity was the formal organisation, or the bureaucracy as Weber called it. This had a clear articulation of rules and everyone was expected to work by them. Rules were formalised through technologies like writing and the use of various kinds of surveillance ensured that the institution’s goals were met. A hierarchical structure and culture was created whereby the top could reliably ensure that the bottom went in the direction the top desired and did not waste time and resources in local distractions. A culture of impersonality was cultivated so that the personal likes and dislikes of an employee could not lead her astray. The rationalised organisation was indeed the most powerful institution ever seen in the world and schools and higher education also began to take on its form. Today’s university and college may say that they are about freedom and truth, or as is being said more often nowadays, about markets and leadership, but the truth is that are the iron cages of Weber, within which human creativity and striving somehow tries to stay alive and take flight.

Weber knew too well the pitfalls of bureaucratisation and his sharp comments on bureaucratised education are just as true today as when he wrote them a century ago. The basic dilemma of today’s education is that we try to find personal meaning out of an impersonal system. He wrote about how the passion and excitement of learning now had to take birth within the dry routine of timetables and the daily schedule of classes. Examinations, he believed, were at the heart of bureaucratisation. They selected and certified people according to whether they were approved or disapproved of by the bureaucracy. The nature of examinations was such that they tended to create people with a certain kind of personality. Those people did well in them who focused on impersonal mechanical knowledge, which could be produced according to the timetable of the education system and written out in a mechanical and efficient manner. The connection of knowledge and learning with the inner voice was a liability in such bureaucratised institutions of education. The better that students learned to suppress their inner voices and feelings, the higher they would go. It was an education system which suppressed charismatic learning to replace it with routinised, bureaucratised performances. Randall Collins (1971, 1979) has enlarged upon Weber’s critique of education to write about the emergence of a credential society. The value of education more and more lies in its ability to create credentials that give entry into status groups and lead to returns in a labour market. The more scarce the credential the greater its demand and vice-versa, the more common a credential, the lesser its value in the market. Intrinsic value is less important than what the credential means for the bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the difference between status groups is what creates the power of the higher ranking groups. Examinations are now a central process for legitimising social inequality.

The strange demand to hold traditional examinations even during a pandemic can only be understood by referring to the characteristics of the bureaucracy. There is a schedule which has to be met and there are certain actions which must be taken. Not doing these leads to the crumbling of the bureaucracy’s authority. If we concede that we can live without examinations then it’s legitimacy and power will get questioned, by people both outside and within it. Maintaining its process is crucial for without it the power of the bureaucracy over our minds disappears.

For all these problems, it is important not to dismiss bureaucratisation and rationalisation in a sweeping manner. Critical theorists have helped us understand the challenges created by rationalisation in today’s times. While several scholars like Horkheimer, Adorno (1972) and Foucault (1995) have had a tendency to reject modernity altogether, it should be noted that there are several like Juergen Habermas (1970) who say that the rationalisation of education is not altogether a bad thing. The growth of a culture of rationality, which is how several people would define modernity, permits us to examine and reflect upon our selves, our government, our traditions. The rational organisation would be able to reflect upon what it is doing and then change its ways of working so as to meet its goals. The problem is not in rationality, but in the privileging of the technical rationality of power over all other kinds of human action – affective, value, traditional and so on. The rationality of moral actions is what should be privileged, not the rationality which serves only deeper structures of power. If we are not cautious bureaucratised institutions run the risk of being taken over by whatever is advantageous to those who are in power. This is unfortunately what has happened in many institutions in India. But there can be an alternative rational conception of the world as well, and several theorists and activists have used rationality to question patriarchy, casteism, capitalism and so on. The rationalisation of education is a doubled-edged sword, it can both cut as well as liberate us.

The problems we are seeing in a higher education which is encountering the material disruption created by the pandemic are the problems of a rationalised era, where that rationalisation only intermittently serves the goal of emancipation. Unfortunately higher education in India before the pandemic was oriented only at a few places towards freedom and empowerment.

Higher education here is quite diverse and has a wide range within it. Let us first talk about the vast majority of Indian colleges and universities which even before the pandemic had little intellectual activity happening in them. They were already giving empty credentials without much substance or intellectual training in them. There was only a pretence of learning which was upheld by the performativity of sitting in a classroom and having a teacher come to read out some meaningless words to them. An examination was conducted in which some memorised or copied sentences were scribbled and a degree was awarded. Today their administrations struggle with the challenge of how to maintain that pretense of learning where that classroom is no longer available. They were not oriented towards intense learning earlier, so that is not really their concern now either. They are worried more about how to give a degree that is legitimate in the eyes of the MHRD and the education bureaucracy. Creating excitement or a spirit of inquiry was far from their eyes earlier and remains hidden from them today as well. They are actually secretly relieved that the new kind of legitimate ways of giving degrees may actually do away with the expense of maintaining campuses and classrooms. If the performativity of degrees can be attained by online classes, then they have no issue with that at all. The thousands of Indian colleges where no teaching used to take place or where a teacher would just come to read out from a textbook are not going to worry about whether meaningful learning is going to take place online. What they worry about is whether bureaucratic processes and appearances can be upheld.

A second category of Indian higher education institutions is where some intellectual engagement did take place earlier on a regular basis. These are a relatively small number of institutions. In most of these, however, there has never evolved a culture of systematically asking what one is teaching for. Universities like Delhi University, HCU and JNU have internalised a deep commitment to their academics and teaching there may be driven by many passionate scholars. However, reflections on pedagogy and how to teach are not common. Learning and thinking about teaching is considered to be a waste of time, which they think is better rewarded by doing research instead. Not surprisingly, most faculty members there begin to feel insecure if they are asked to rethink their teaching. They have never been taught how to reflect upon teaching methods and believe that the way they were themselves taught is good enough for the next generation too. Unfortunately, whatever may be the egalitarian beliefs of these teachers, this kind of teaching is inherently exclusive and discriminatory. Students who do not perform as per expectations are declared to be “weak” students, without asking whether the problem actually lies with the pedagogy and not the student. Frustration with the online mode is very high among the teachers of such institutions. They are keen to have a meaningful exchange but have not learned to think about teaching and as a result they are ill-equipped to adapt to this new environment. Teachers diligently prepare their one hour lectures and read them out in the same old way over the internet. Unfortunately, what worked because of the charismatic, dramatic presence of the teacher in the classroom falls flat on a video screen with a jerky internet connection. Not surprisingly, most students lose interest after a few minutes and concentrate eventually just on passing the bureaucratic procedure of the examination.

A third category within Indian higher education is an even smaller one. It is made up of a few teachers in the above-mentioned institutions and an occasional rare institution as a whole which takes teaching and pedagogy seriously. Here we find teachers who have switched into a very interactive mode of teaching. They give many more examples, do online discussions and activities with students and use photos and videos to hold their interest. Instead of talking for twenty minutes before asking a question, they talk for ten minutes and then spend the next five minutes hearing students respond to a question. Because holding students’ interest takes time, they drastically cut down on their syllabus to pick up instead just a few topics to emphasise. Here we see people who are holding onto that key attribute of rationalisation and modernity – they are thinking about what has happened and are actively trying to find ways of teaching well even in the changed circumstances. They are not just carrying on with the same rituals or being paralysed in the changed environment. Many alternative ways are being thought about and found for adapting to the change. Instead of closed book traditional final examinations there can be given a series of take-home assignments which test the understanding of students. These can be done at home and sent by email. They can be designed in a way such that there is no fear of copying. Such assignments would be about understanding and application, not about memorising sentences and paragraphs. The reflective teacher knows that the online mode can never be as good as face to face teaching, of course, but still tries to find many ways to teach well even in the era of Covid 19. The reflective teacher responds by reducing the syllabus, increasing interactions and keeping on doing higher order teaching, emphasising not just memorisation but analytical, evaluative thinking as well.

One of the biggest problems facing higher education in India today is that the first category of institutions is huge, the second is small and the third is tiny. This is what we get when we privilege holding on to power in institutions over and above asking what the purpose of teaching and learning is and when we do not focus on better ways of achieving that purpose.

Social Inequality

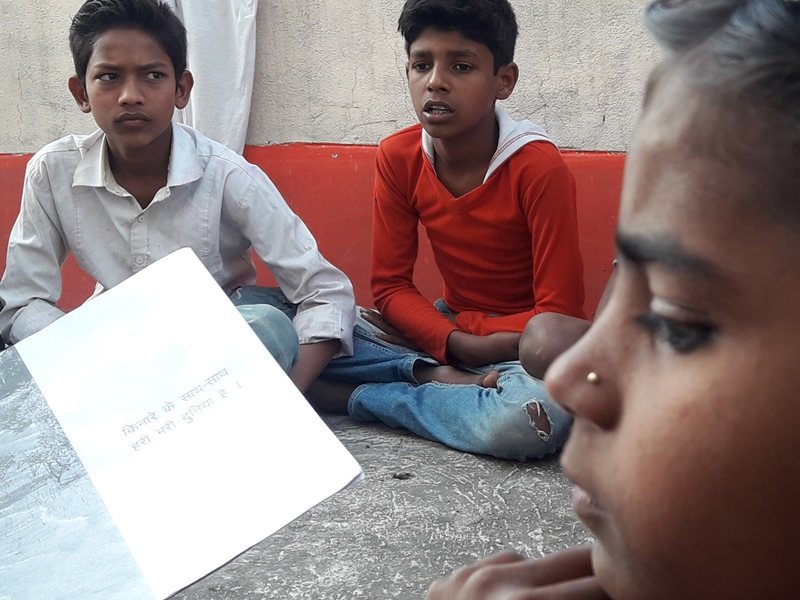

Let me turn away now from the dull and unthinking way in which we run our institutions into a second major challenge facing higher education today. This is the problem of social inequality. This too is an old problem and our educational institutions have long been turning a blind eye to it. Now that old problem is leaping up at us again in a new way. We are as we all know, a country of vast social inequalities. In the first place just about 25-30% of our young people can afford to any kind of higher education. Then within this student body too there are many further disparities. The shift to online classes has suddenly reminded us of the importance of the classroom. There is a long history of many efforts which took place to bring a few students from weaker classes, castes, genders and regions into this classroom. It took many struggles for them to make it into the classroom to sit alongside the more privileged. To be sure, many injustices kept striking them there too. Teaching was done in the languages of the powerful, alien examples coming from the lives of the elite would be given, peer groups of the privileged would form that excluded them and so on. But at least they were able to be present in the classroom. Now even that has slipped out of the hands of many of them. This new turn has led to an important material asset which had been provided to the socially disadvantaged being struck away. Today students must depend upon their own families again to find the material basis to be able to attend class. They need computers, smartphones and and a strong internet connection. Along with that they need the money to buy data so as to attend four hours of classes every day.

The inequalities of resources and of regions have reared their head again in a dramatic way. Those with more resources can now participate in online classes with full video running on both sides. Many can only listen and that too with breaks and jumbled words. And some cannot even get a signal on their mobiles in their homes. Not surprisingly, many socially discriminated communities find that their mobile signal is the weakest. Women students tell of the special challenges they are facing. While at home they are under tremendous pressure to do house work and they find it difficult to attend classes. Often they are trying to listen to the teacher while cooking or cleaning at the same time. In college and in the classroom they were exposed to other social violences but they were removed at least for a while from the dynamics of the family. Sitting at home to do their classes they are now again subject to all the role expectations of a patriarchal culture. Even talking actively and vigorously in a classroom discussion in front of family members can attract disapproval. We used to think of the classroom as a dull entrapped kind of space. Now we have become aware of how for a number of students it was actually a space which had greater freedom than the home.

Manuel Castells (1999) had been one of the early people to ask what this rise of a new informational age would mean for social inequality. The industrial age had been replaced by an informational age he had said. Now the new forms of inequality would depend upon who was central to networks and who was peripheral to them. While teaching this semester I could see that most dramatically when students in remote areas struggled to hear me. Students told about running out of data and being unable to attend the last class of the day. I was fortunate that I was in an institution which had provided laptops to students who could not afford them. Students who needed them were also quickly given additional scholarships to buy more data. But this was a rarity. Most institutions just passed the ball into the laps of families. Social inequality was then sharply mirrored into the ability to access learning, in a more acute form of inequality than we had seen in ordinary classrooms.

We need to think afresh about what we need to do create equity in education in this online era. At the minimum governments must be put under pressure to give good internet to all students. Hardware needs to be installed on an urgent basis. Students should be provided with the material resources needed to be able to learn. A fresh commitment is called for towards making all students welcome in online classes and towards facilitating their learning.

Let me stop by saying that a deeper system of social inequality is manifesting itself again but in new ways. Historically social science has sometimes grown when there is a break in social arrangements. Such a disturbance in social norms and practices had led to the emergence of Sociology and Anthropology in the first place two centuries ago. Perhaps this new disruption of what we had become accustomed to may lead to new interpretations and new calls for social change. Perhaps teachers and administrators will again begin to ask what is the purpose after all of what we are doing. Maybe this rational reflexivity will lead to pressures to provide equality and equity in education.

The above article is a revised version of a lecture given at National Webinar Series, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, 14th July 2020

REFERENCES

Castells, Manuel. 1999. “Flows, Networks and Identities: A Critical Theory of the Informational Society.” In Critical Education in the New Information Age, edited by Rámon Flecha, Paulo Freire, Henry A Giroux, Donaldo Macedo, Paul Willis, and Manuel Castells, 37–65. Lanham: Bowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Horkheimer, M., and T.W. Adorno. 1972. Dialectic of Enlightenment. New York: Herder & Herder.

Collins, Randall. 1971. “Functional and Conflict Theories of Educational Stratification.” American Sociological Review 36 (6): 1002–19.

———. 1979. The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification. New York: Academic Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

Habermas, Juergen. 1970. Toward a Rational Society. London: Heinemann.

Madan, Amman. 2014. “Max Weber’s Critique of the Bureaucratisation of Education.” Contemporary Education Dialogue 11 (1): 95–113.

Saberwal, Satish. 1995. Wages of Segmentation: Comparative Historical Studies on Europe and India. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

———. 1996. Roots of Crisis: Interpreting Contemporary Indian Society. New Delhi; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.