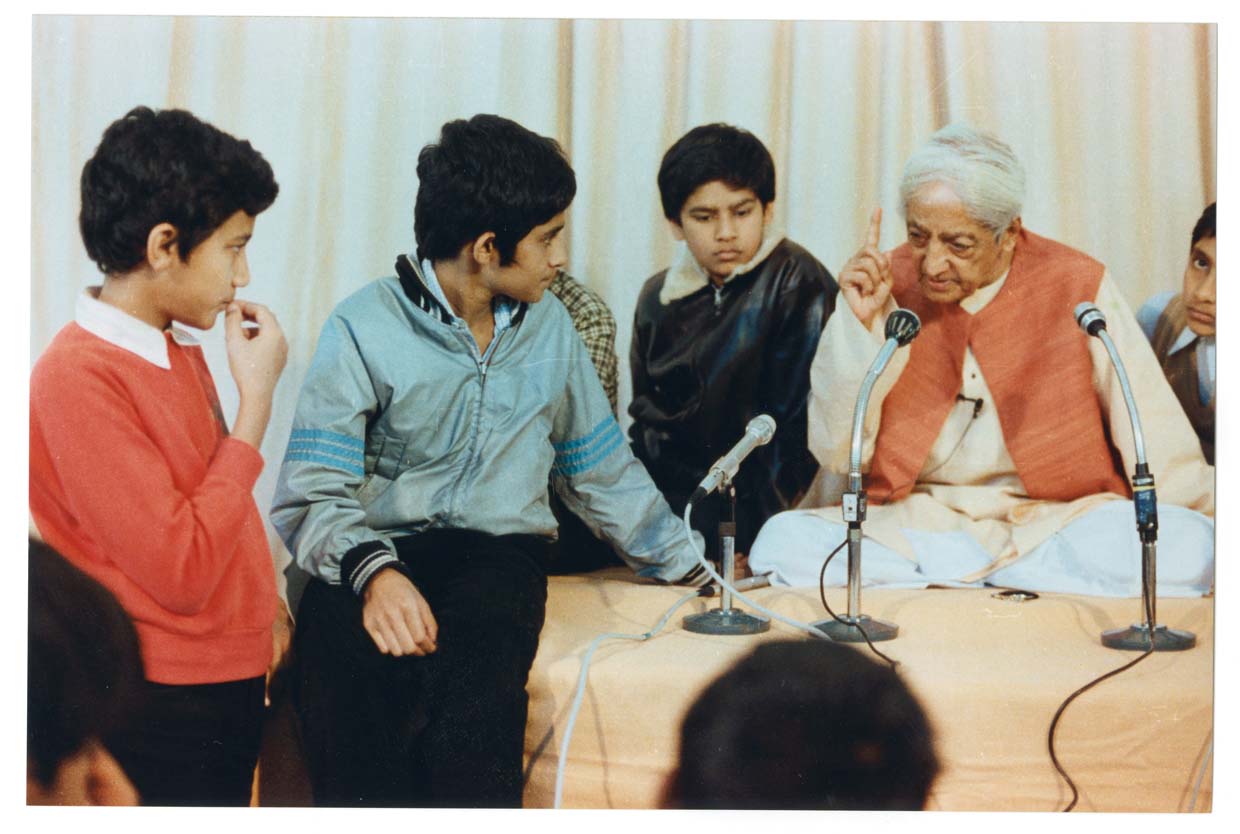

In a valley surrounded by ancient hills, with farmers and shepherds as neighbours, nestles a community of concerned educators whose main task is to engage with the children in their care, to bring about a new generation of human beings. In 1926, when J. Krishnamurti chose this piece of land, close to his birth-place, he envisioned the setting-up of his first educational institution. Since then, many administrators, workers, teachers and students, have passed through the school, several here for a ‘good’ education, others engaged in making that possible, yet others trying to provide support in different forms, and all together, as one amalgamated unit, working together to provide an ethos that children remember years after they have graduated from school. Children themselves bring their perspectives, actions and behaviour to this space, creating meaning and giving life to an institution that would actually be bereft of life if it was not for their presence. This coming together of different persona in one space, to partake of a process that is about learning together and living together, is what creates the culture of the school. Schools are spaces where such school culture is an inevitable part of everyday life.

School ethos or culture is not made up of the trivia of school life. As educators, we often imagine that it is and therefore pay so much attention to the detail of the routine, the schedule, the manner in which we keep children, and ourselves, occupied throughout the day. More than the school routine and the everyday academic life of the institution, school culture is however a process. How then, do we define this process? What is this ethos, this culture, that prevails in an educational setting that is not about academic scholarship alone, that liberates even as it circumscribes, that helps one to push one’s boundaries as teachers, and as children, that enables a rich understanding of the multi-dimensional facets of life,

and simultaneously expects one to be ‘good’ at what one does. Krishnamurti did not accept mediocrity as a virtue in the same way as he did not cherish the burden of memory, that is embodied in knowledge, which we worship, as representative of truth. Instead, he asked us to look, to listen and to learn, as if we were doing it for the first time. In other words, to be fresh in our approach to learning. There would in this way never be a mere accumulation of knowledge or the regurgitation of what may be considered legitimate knowledge, but an understanding that comes with intelligence, empathy and compassion.

This takes us to relationship that is a central constituent in our lives. Schools are spaces where we must understand ourselves and others as mutually interdependent human beings in relationship to one another and to the world we inhabit. Relationship is the sine qua non of school life. We relate to people, to ideas, to nature and to everything around us. In other words, to cite Krishnamurtis axiomatic statement, ‘you are the world’, would not be an overstatement. Understanding the breadth and depth of this assertion brings about a tremendous sense of responsibility as participants engaged in living and learning together in an educational setting. This responsibility must not be only concerned with our petty little worlds, as Krishnamurti often said, but is about the whole existence of life. ‘To be is to be related’, is another of Krishnamurti’s oft quoted statements. We do not exist in isolation and when we understand this, not merely intellectually or theoretically, but viscerally, with a sense of conscious awareness, we can never experience ourselves as only an individual in a bounded or enclosed space that is ours alone. This requires an understanding that we need to stretch ourselves outside our known universe of comfort and privilege, our closed circle of allies and acquaintances or clique of intimate friends, to understand the lives and experience of others who may be less privileged, have no access to education or livelihood opportunities, who may speak a different language, or have a special faith, a unique life story, and so on.

Is it possible to bring this expanded idea of the individual to our children in the everyday life of an educational setting? Pushing out the boundaries of the self is not unimaginable or impossible. With time, children may come to understand that it is possible to see the other who may look different, or belong to another community or caste, as part of a larger inclusive whole in which we are all connected as a disparate but collective entity. This is possible only if we allow children to actually ask questions about issues of identity and respond to them equally honestly. Identity is not a fixed idea or experience. It is in movement, it is fluid: I experience as many aspects of myself at the intersection of multiple facets of being a person as does everyone else. The space for dialogue in everyday life requires an ethos that is open to questioning, to honest conversations about ourselves and others, to explore nuances of relationships that are often unexpressed or remain outside

the field of formal education, per se. This once again comes down to school ethos, maintaining an ethos that is conducive to such conversations and to enabling a more non- violent and just social world.

Meenakshi Thapan was Professor of Sociology at Delhi School of Economics. She works at the Rishi Valley Education Centre (KFI), Rishi Valley, Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh.