In the backdrop of UN secretary general Antonio Guterres’s advice to India about scaling up clean energy activities and phasing out fossil fuel activities, the debate about climate inequality has emerged once again. Guterres, at the 19th Darbari Seth Memorial lecture on 27 September 2020, lauded India for its increasing investment in clean energy, particularly for initiatives like the International Solar Alliance, but criticised India for subsidising fossil fuels and promoting coal auctions. This statement opens up the contradictions within global climate change policy starting from Copenhagen Accord 2009 to Kyoto Protocol 2012 and now Paris Agreement 2015. Five years after the Paris Agreement was signed by over 160 countries, there is still a large gap between promises and implementation. The contradiction that plagues the policy remains that the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases are the countries in the global north while the biggest threats of climate change are being borne by the low and middle income countries of the global south. Another brand of the same contradiction is that by expecting developing countries like India to make no new investment in fossil fuels like coal and to reduce emissions at par with developed countries is a call to de-industrialise the country and abandon the population to a permanent low-development trap. Both arguments point to the disproportionate share of the climate change burden being borne by the poorer and the poorest nations.

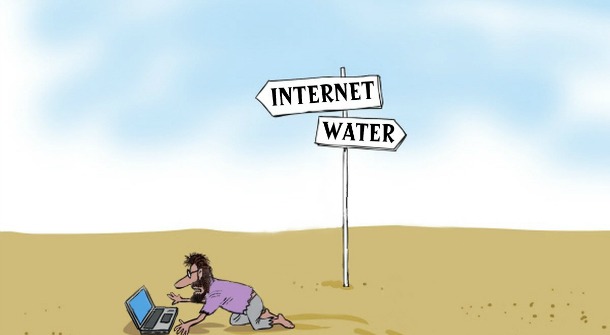

According to Oxfam’s 2015 report called Extreme Climate Inequality, around 50% of total emissions can be attributed to only 10% of the richest people in the world with interests in fossil fuel activities such as coal industrialists. The lifestyle emissions from the large economies contribute massively to the climate change, and on an average these are higher than those of the rich in middle income economies. The question then is, with much higher responsibility on the end of the global north, why is the UN pressurising countries like India and China to meet climate goals identical with those of the US or the European nations? In accordance with the principles of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a sharp distinction must be maintained between the responsibilities and commitments of developed countries vis-à-vis those of developing countries.

Antonio Guterres’s remarks at The Energy and Resources Institute in August come as India is set to boost up its coal activities, even as it is lagging behind the 2022 target of carbon emissions reduction. The coal-fired power plants are still at preliminary stages of compliance with the standards for desulphurisation and reduction in particulate matter emission. Under the Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, Indian government recently opened up the coal sector to commercial mining. This June, the prime minister launched the auction of 41 coal blocks for commercial mining, given the mission to become self-reliant in the energy sector. The mission allocates Rs 50,000 crore on creating coal extraction and transport infrastructure, which will also create lakhs of jobs according to the stated objectives. While this expansion is directed at easing India’s burden of coal imports, the reforms also promise a commitment to invest around Rs 20,000 crores in projects towards coal gasification.

Guterres’s advice to India on multiplying investments in renewable energy resources to achieve poverty alleviation and energy access targets are therefore pertinent but unfair due to its inadequate allotment of responsibilities. India’s annual emissions stand at 0.5 tonnes per capita, well above the global average of 1.3 tonnes. While India was responsible for 4% (for a population of 1.3 bn) of cumulative emissions by 2017, European Union was responsible for 20% (for a population of 448 million) of emissions by the same time. Moreover,as per their rate of emissions, the mitigation efforts of the developed nations (except Russia and east Europe) have contributed to only 1.3% reduction in annual emissions between 1990 and 2017. The global north continues to rely heavily on fossils- natural gas and oil- with no attention to a phaseout timeline. Climate mitigation arguments of the developed world are thereby discriminatory as they demonise coal-based energy activities of the developing nations and conveniently exempt themselves for their own fossil dependence. Hence, the talk over “carbon neutrality” is being accused as being an exercise in moral posturing consistent with the supremacist nature of the developed world.

In addition, such talks discount the industrial and agricultural productivity of the low and middle income countries over the pursuit of climate change policy. India’s present capacity for renewable energy is insufficient to meet the domestic-residential, industrial and service sector demands. To make a transformational shift to renewable sources, manufacturing growth powered by fossil fuel-based energy is itself a necessity, for developing or acquiring the technologies required for producing renewable energy. Acquiring these resources will need India to depend further on external sources and supply chains, making the situation especially hard owing to the pandemic. The pandemic, having exposed the vulnerabilities of both small and large economies, has set back the progress as well as priorities of all countries towards climate change mitigation projects. In these challenging times, should the responsibilities of climate change mitigation be eased for countries like India?