Different interpretations of peace

I learned about the killing of the Dalit 9 year old Inder Meghwal from some of my students. It seems Inder was beaten to death by his teacher for touching an earthen pot of water kept for “upper-caste” students. My students were livid with anger and held a solidarity meeting after Independence Day celebrations to share with each other their fury and frustration that such a thing could still happen in our country. Some of them had not been able to sleep all night, they said. In the meeting they talked about many things which they had themselves seen or experienced. They urged the members of their audience to break out of their passivity. We should all be shaken out of our comfort zones and ensure this never happens again, they declared.

Their anger and outrage left me with many questions for myself. Particularly about peace and tranquility. What was the role of peace in issues like these? These students seemed to be arguing against peace, were they wrong? What is the place of peace in human life in general? In this article I take a look at some of the different perspectives on peace and ask what they are trying to achieve (or not achieve).

There are several different ways of looking at peace and peace education today. The Gandhian approach is well known in India. Similar but different are the approaches of Indian philosophers like J. Krishnamurti and Aurobindo. We also have here a human rights approach promoted primarily by the United Nations. Less commonly known in India are approaches to peace coming from critical education and the way anti-war peace movements and civil rights movements in west Europe and North America developed into peace education.

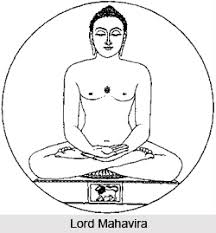

Peace (Shanti or Ahimsa) has a very long history in Indian philosophy. While ahimsa was not a very important idea in the Rig Veda it emerged as an important principle in the Chandogya Upanishad, which was probably composed some three thousand years ago. We do not know if Jain philosophy emerged before or after the Chandogya Upanishad, but ahimsa is at the core of Jainism, where it is the key to a life following dharma, the correct moral order for our world. Ahimsa also took up a central position in Buddhist philosophy, which in turn influenced Yoga.

Jain philosophers believed like most other Indian systems of philosophy that the purpose of life is to gain moksha. According to Jain philosophers we are obstructed in this by our karmas which weigh down our soul and prevent it from acquiring that condition. Our wordly life with our concern for wealth and power continuously creates turmoil in our mind and blocks our soul from gaining the purity it needs. Ahimsa is one of the ways of cleansing the soul. Jains believe in the equality of all souls. By loving everything and not causing it harm we wipe our soul clean of the karmas which blot it. Learning to love everything is central to ahimsa. This has a negative dimension – that of not hurting anyone – and also a positive dimension – of doing good to others. These ideas of Jainism, ahimsa and love of all as the way to gain moksha had a great influence on many subsequent philosophers.

We find similar ideas in the subsequent development of Buddhist philosophy where ahimsa and compassion (karuna) are of great importance for attaining nirvana. A lot of Buddhism and Yoga’s activities and rituals are about silencing the inner mind and stepping away from the thoughts and actions which corrupt us. When the many pulls on our self get calmed down, that is when we will be in a state of peace. These are also the ideas we see in Jiddu Krishnamurti’s writings on peace. He writes that when the ideas and feelings that run riot in our mind get silenced, that is when we will get peace. In all these Indian philosophers we see an emphasis on changing oneself so at to walk the path to peace.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was raised as a Jain and we see these ideas resonate all through his life and work. But, Gandhi adds a very interesting and new dimension to Indian thinking on peace. When I remember what my students were raging about, I realize again that he had added something more to the way peace was thought about by the philosophies I mentioned earlier. Gandhi learned from some western philosophers and social theorists about how social relationships, the way we work and the way we live can affect our mind. This leads to a new emphasis. To find peace we cannot just try to resolve the voices fighting within our minds. We cannot just walk away from the fights happening outside to go to the forest in search of peace. Instead, we must try to build new social relationships, new institutions in the world. I think my students would appreciate this aspect of Gandhi.

Gandhi combines the search for inner peace with the search for new relationships in the outer world and insists that we cannot get the first without the second. For instance, British colonial rule was responsible for many of our troubles. It exploited and impoverished us economically and denied us respect and recognition too. Citing the Gita and the Mahabharata, Gandhi believed that to withdraw into a search for inner peace would be an act of cowardice. Instead, peace was to be built by changing the British through love and moral force. He sometimes acknowledged that behind that moral force there also stood the raw muscle power of a vast mass movement for freedom. The Manusmriti could talk of ahimsa while also denying vedic education to the Sudras and women. In Gandhi’s way of thinking this was irreconciliable. For Ahimsa one did not rebuild things only within oneself, but outside of oneself too. There could be no moksha if there was violence against less powerful castes and women or against Indians as a whole. This search for peace both within and outside in the social is also seen in the work of Thich Nhat Hahn, the Buddhist monk who campaigned against American interventions in Vietnam. He taught meditation, he said, as a way of gaining strength to fight against wrongdoings in the external world.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s approach to non-violence comes from another religious and cultural tradition but has many similarities with Gandhi. The Pathans had a long history of standing up against invaders and celebrated defiance and revenge. Khan drew from the example of the first twelve years of prophet Mohammad’s practice of Islam when he and his followers peacefully stood up against all manner of abuse and violence without retaliating. In Islam one found peace through submitting oneself to the will of Allah. Doing this without hurting others was what the prophet had successfully managed to do in his early years. This was “sabr” or patience, Khan said, and was essential for Islam’s message of peace and love of all. He said to the Pathans that the highest form of proud defiance was not to take to arms, but to stand firm and be willing to die in the service of others. Khan organized the Khudai Khidmatgars as a non-violent army and started with social work. Later they found themselves in opposition to the British because of their harsh misrule and set up for a while a parallel revenue and civil system to the British. They actively protected Hindus and Sikhs and insisted that women come out to participate in public life. Social reform and standing up non-violently against all kinds of injustice was for them the meaning of Islam.

A somewhat different approach towards peace from that seen in India gained momentum in west Europe and North America as a result of the world wars of the twentieth century. Notable authors and philosophers like Herman Hesse and Bertrand Russell declared that the rivers of blood flowing across the world were little more than madness and distanced themselves from war and jingoism. In these war-torn countries peace and peace education was mostly about preventing war. The early efforts to educate children to respect and not hate citizens of other nations became after the second world war an effort to prevent a nuclear holocaust. Peace movements focused on pulling countries like USA and USSR back from the edge of a brink which threatened to wipe out humanity as a whole.

These peace movements were transformed by the emergence of several popular movements in west Europe and North America. Civil rights movements emerged that highlighted the violence which racism and social inequality perpetrate. The feminist movement brought attention to the many kinds of overt and covert violence which occurs in gendered relationships. Labour movements and environmental movements drew attention to the role of capitalism and greed in creating a profound violence in the social world and its ecology.

A new and more comprehensive theory of peace emerged in the work of peace scholars like Betty Reardon and Johann Galtung. Galtung for instance, distinguished between personal violence and the structural violence which racism and patriarchy created. This included intangible and invisible forms of violence like creating feelings of superiority and inferiority and draining away people’s confidence to speak up. To work for peace meant addressing two fronts at the same time – (1) reducing the possibilities of war and physical violence and (2) reducing structural violence. Many peace activists combined these with the aforementioned emphasis on inner peace as well.

Feminist theory, critical pedagogy, and theorists who work on the politics of culture have helped to better understand the way structural violence oppresses without even the apparent presence of physical violence. Paulo Freire and bell hooks are amongst many others who have analyzed how power operates through culture to create feelings of inadequacy and leads to the acceptance of the point of view of the powerful. Across history this has led oppressed groups like Dalits and women to begin to speak in the language of their oppressors and to accept their ways of thinking. Freire wrote about how important it was to empower people so that they could understand the roots of their problems and break out of false mythologies. Freire and bell hooks both said that an attitude of love was the key to struggling against all oppression. bell hooks drew from the feminist tradition of an ethics based upon love and care and argued that we had to rethink and redesign love, since even love could be made the tool of oppression. Freedom from violence meant the practice of love in a way that did not force actions or beliefs upon others. Instead love meant working for the well-being of others. Loving and caring for others in a way that overcomes histories of oppression was really what peace was all about. This approach has come to be called critical peace and practices a critical peace education.

So the study of social life has given us a sharp awareness of the contribution of social structure to violence and peace. Contemporary social theory believes that we must be sceptical of all narratives that offer a long-term perspective. It also believes that the world is actually made up of continuous conflicts and we cannot dream of an end to them. This contributes a distinct perspective on peace, which may sound a little counter-intuitive: conflict and violence are actually inevitable in human society, what we need to do is to channelize them and steer away from their worst manifestations. Differences between points of view are everywhere, even amongst the best of friends. Coercion of some kind, too, is inevitable in social life. Even when we teach a baby to defecate in one place and not another that, too, is a kind of loving violence. When we build a legal system that says people who deny respect and opportunity to the children of the poor will be put into jail, that too is a form of violence which we practice. In other words, power and violence are everywhere. What distinguishes between acceptable and unacceptable forms of violence are the degree of moral legitimacy they enjoy. For instance, the kind of gentle power we use to get children to learn that they should focus their minds and work hard is considered acceptable since it is beneficial for them as well as our kinds of societies. We should not claim that we are not using any kind of violence. Instead we should focus upon questions like how we decide what to do, which kind of pressure is acceptable, which is not and so on. We should try to find answers through processes that emphasize dialogue and a genuine attempt to understand each other. Our choices should be made through a morality of love and justice, not one of domination, fear and hatred. This is indeed possible when there is a strong culture of dialogue and fraternity. However, an imbalance of power makes it tempting for the powerful to refuse to listen and engage. Balancing out their power through protests and mass movements compels them to listen more carefully. This approach believes that the term “peace” is sometimes confusing since people assume it to mean the absence of power and coercion. Instead it may be better to talk of a politics of dialogue and love.

Only saying that one is searching for peace becomes a little confusing. One should also say that one is searching for justice and a world built upon moral arguments, rather than upon arbitrary power. For this we will need to strengthen many elements which people working for peace have celebrated: knowing oneself, recognizing and overcoming the elements of fear and hate in oneself; cultivating dispositions of love and care; understanding and acting against immoral and unjust social, political and economic systems. We also need to learn how to come together and build the strength of a collectivity that stands for moral arguments. This is about cultivating the ability to listen and to have a dialogue. We need to strengthen conflict resolution processes that privilege dialogue and promote transformation through conversations and experiences, rather than try to control those who disagree with us through force and violence. Many contemporary philosophers of ethics will point out that it is impossible to build a single ethical vision. So we also need to learn to respect other social groups and be willing to care for each other while we continue to discuss and disagree.

Perhaps people like Gandhi would recognize this is nothing but the struggle for ahimsa, while being a little more elaborate about the power, knowledges, skills and attitudes that it calls for. Acknowledging that this is a politics of dialogue makes it clearer that prem and ahimsa must work through morally defensible power and does not exist independently of power.

When I think again of what my students were saying about their horror at the killing of Inder Meghwal, I see in them the anguish that comes from seeing human love being shattered and betrayed. How could someone be so dehumanized that he could kill a nine-year old in the name of caste? I admire the truthfulness of my students who could see how wrong this is and their honest pain at it. They were not amongst those whose social location and busy life had numbed them from feeling the horror of such an act. They had been able to push back against a normalizing power to retain their humanity.

It is now important to move from the perception of moral horror to actions that will transform those who were the perpetrators of it. My students were very angry. Anger comes from a deep agitation in our mind and serves us through intensifying our motivation to act. This can be done in a self-destructive way that hits out randomly at anything within our reach. Or it can be channelized to fuel a deep communication that transforms the attitudes and thoughts of those who we believe have done wrong. At some point anger must change into a love that transforms. How does one change the ideas, beliefs, practices, emotions of those who beat Inder? They may get silenced out of fear. But that will remain yet another act of violence and not be a real transformation. When they change because they feel that they were wrong, when in their hearts contempt and hatred are converted to respect and love, when they feel guilt and repentance, that would be a real change. The politics of dialogue cannot go far with anger alone. It must cleanse its own anger and build its strength so that it can through love help others to discover their errors.

Prof. Amman Madan teaches at the School of Education, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.He writes extensively on issues related to education, social stratification, social theory and identity politics.