State governments need to spend much more on education than what they do at present. No one would doubt that. What however becomes invisible is fact that incremental increases can’t tackle the huge back log created by underspending over decades. Today it is possible to quantify more accurately the current requirement. This is because we have norms laid out in the RTE Act and following some reasonable assumptions & using school wise U-DISE data we can estimate what should be spent. Comparing this with current expenditure shows you the back log.

It is crucial to focus on the initiative or neglect of state governments. State governments have the prime responsibility for mass education and their outlook & attitude make a significant difference. In our study with colleagues from NIPFP we found that 15 states or union territories could raise their own funds, if they were to set their sight on assuring the norms as per RTE. The rest would require substantial financial support from central government. The initiative of state governments is crucial mover also because the central government has been drastically curtailing the demands of states for enhanced allocation towards Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan in its budget.

Delhi is a good example to discuss because despite the political visibility & initiative for education the backlog is immense and the needs of the poor still remain invisible. It is also one of the states that can raise money from its own sources.

The allocation for education as recently announced by Delhi government is around 21% of the total budget. This is a decent allocation and subscribes to the NEP thumb rule to keep education state budgets above twenty percent. This would allow the government to keep focus on its plans that include, among other targets, 17 more B R Ambedkar schools of Specialized Excellence & additional computers for all government schools.

The question that needs to be asked is whether the current level of allocation is adequate for the needs of the city state. One must

remember that Delhi contains many cities within itself and that there are layers of low-income areas, resettlement colonies, unauthorized slums that may be grouped as the ‘urban fringe’ areas.

My colleagues from NIPFP in their paper point out that the addition of classrooms to existing schools is required but not sufficient. Delhi requires many more new schools. Their estimated figures are 632 composite (K-12) schools and 275 primary schools over the next five years. This is a large number. There are four factors that drive this demand. For a large number of existing schools, the shortage of classrooms is acute-new classrooms required are more than the current available space for additions. Of children now attending ramshackle low fee schools, because of no other choice, probably half would shift to government schools, if access was provided. A large number of children in the urban fringe areas currently out of school could be brought in. The likely demand from population growth over next five years has been taken into account. It’s important to realize that while one appreciates the move to add additional classrooms to existing schools & also use many of these schools in double shifts, the back log of what is required is huge.

The Delhi government is best placed to do a school mapping exercise for each school cluster that would show in specific where shortages can be met by additional classrooms, double shifts as a fallback arrangement for the short run and where new schools would be required. Most difficult exercise of them all-how would land be identified & acquired for the new schools.

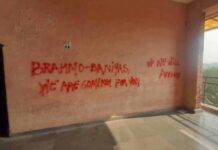

How are people coping with these shortages? Over the years large numbers of low fee private schools have sprung up in the urban fringe areas. Some are recognized schools and many are not. These are cramped schools often in unsafe buildings & low paid teachers, similar to sweat shop labor with no social security. They however they serve a refuge function.

The Delhi High Court in a judgement regarding banning of unrecognized schools at Delhi in said, “Though undoubtedly in terms of Sections 18 & 19 (2) of the RTE Act also, after 31st March, 2013 unrecognized schools cannot in law function but we (The Court) cannot shut our eyes to the harsh reality, of the children studying therein being left without any school to go to, if a direction for immediate shutting down of the said

schools were to be issued.” The back log is huge because of public neglect over decades and the loss of trust in running functional government schools.

There’s a virtuous cycle that the Delhi government has started. As governance of government schools improves the demand for these schools are going up. Other studies for rural areas have also shown that people desire functional and adequately staffed government schools.

Low fee private schools are a choice in distress. Investment for additional classrooms & schools has to go in tandem with better management of public schools. Unless this trust is restored through better governance, investments alone can never solve this problem.

What is the level of additional funds required for schools and teachers? Investments of up to 0.71% of GSDP of Delhi, implying a 50% increase on the present level being spent on education would be necessary to cover both infrastructure and teacher gaps. While NEP bench mark is a thumb rule but it is totally inadequate to cover the back log. Incremental increases would not suffice. Therefore, the Delhi government needs to initiate its own medium term planning exercise.

Where would these additional funds come from? In an ideal scenario this should come from the central pool, at least the additional capital expenditure required. However, given that the central government has been slashing down the demands for all states, this source in the present context appears unlikely. The Delhi government has to think of additional local taxes, education cess or other creative avenues.

Arvind Sardana is former director, Eklavya Foundation, a non-profit, non-government organisation that develops and field tests innovative educational programmes and trains resource people to implement these programmes. It functions through a network of education resource centres located in Madhya Pradesh.