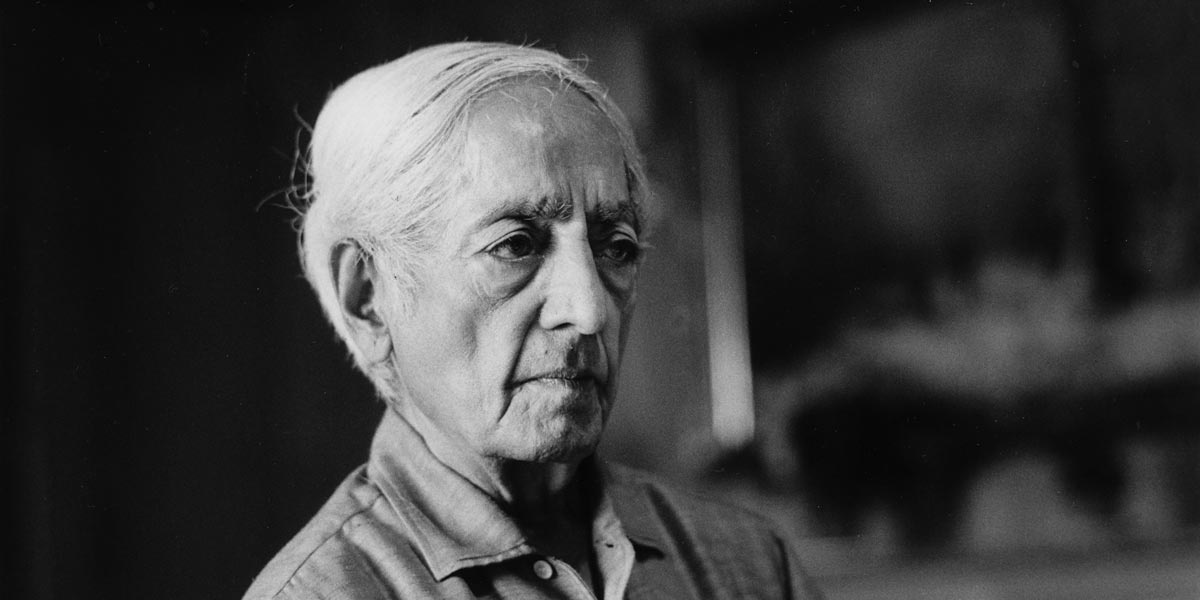

As a student of social sciences, I have allowed myself to expand my mental horizon through the discourses of a spectrum of thinkers. In a way, I cannot say that I belong to a particular school of thought. In my mental landscape, Gandhi and Marx play together; or, for that matter, Jalaluddin Rumi and Gautam Buddha; or Tagore and Dostoyevsky have become my companions in the process of making sense of the world, or the dynamics of culture, society and human longing. Well, my mind is not fresh or innocent; nor is it free from the baggage of what can be regarded as ‘knowledge’ based on books, thoughts and memories. Yet, I am open to the process of unlearning. Possibly, this quest for unlearning or dialogic spirit did arouse my interest in Jiddu Krishnamurti. In fact, when I was a university student, I was lucky to see him, and listen to his illuminating talk in New Delhi’s Constitution Club lawn. Yes, the journey began… I started reading his books; and these days, thanks to YouTube videos, I listened to his talks quite frequently. My social science-oriented ‘academic self’, and associated ‘conditioning’ could not succeed in preventing me from engaging with Krishnamurti’s ideas. Moreover, as a teacher (and a teacher, I feel, is primarily a student; and a student ought to be a wanderer/seeker), I cannot escape from his deep reflections on education. In a way, Krishnamurti, to me, is irresistible. Even when I fail-and fail more frequently—to internalize his teachings, I try to come back to him time and again. Let me give an illustration. I often reflect on the meaning and implications of fear—say, the fear of death. Right now I am vibrant and alive. However, I am thinking of tomorrow. Tomorrow a serious disease might inflict my body; or I might die in a road accident. And I am afraid that if I die, nothing will remain of ‘me’, or what I possess—my ‘name’, my ‘fame’, my car, my property… Yes, when Krishnamurti says that ‘fear is always in time, because time is thought’, I cognize it intellectually. I am not living in the moment here and now, and letting it go. And hence, I am afraid of tomorrow. And it is this fear of the future that leads me to acquire money, power and fame. As Krishnamurti says, what we are afraid of is the coming to an end of the ‘me’ that has acquired so much money, that has a family, children, that wants to become important, that wants to have more property, money.” Yes, I understand it intellectually. Yet, I am not free from fear. Hence, I must confess that my intellectual/academic understanding of Krishnamurti does not necessarily mean that I have truly internalized it, realized it, and experienced it. Despite this vulnerability, despite these failures, I cannot escape Krishnamurti. I experience an irresistible urge to engage with him time and again. Possibly, this essay is an articulation of this endless quest.

Three Issues

Well, in order to give some order and coherence to the essay, I will invoke and bring Krishnamurti in the process of reflecting on three inter-related issues that bother me. And I hope my readers too are equally concerned about these issues. First, in this hyper-competitive age of social Darwinism and gross consumerism, how do we rethink education? Should education only equip our children with a set of technical and cognitive skills, and transform them into ‘products’ for the techno-corporate market? Or, should we reimagine education as a praxis of liberation? Second, in this age of hyper-nationalism and militant religious identities when our consciousness is becoming increasingly parochial and exclusivist, is it possible to be free from this sort of conditioning, and evolve as sensitive, humane, dialogic seekers and wanderers free from all sorts of orthodoxies and indoctrination? And third, when the market-driven logic of neoliberalism has given birth to a profitable industry of all sorts of fancy gurus, babas and motivational speakers, is it possible for us to be free from this trap, trust our own inner journey and quest, evolve as seekers rather than consumers of instant spiritual products like—‘how to detox your mind in two minutes’?

Rethinking Education

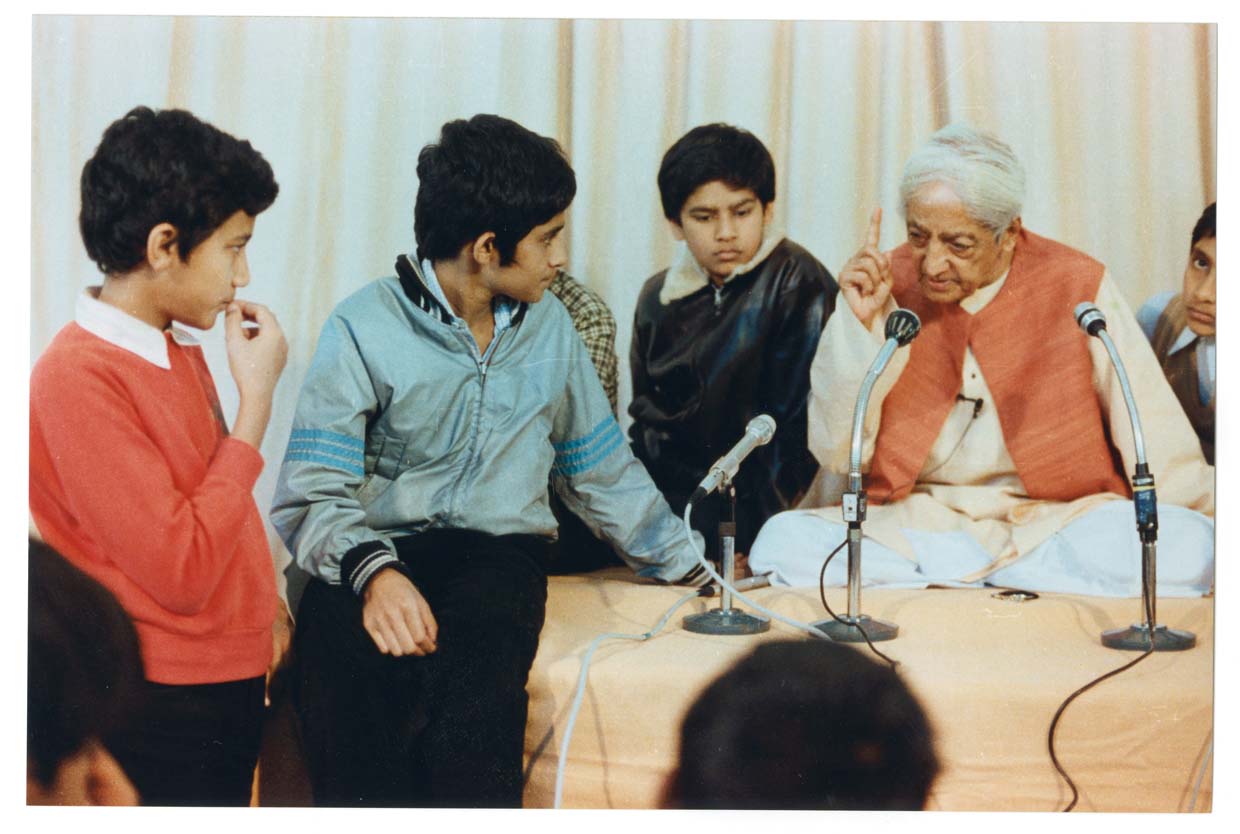

Let me begin with the first issue relating to the state of education. Enough has been said about the sickness that inflicts the mainstream pattern of education in the country—rote learning, sole preoccupation with the quantification of ‘success’ in terms of, say, 99% marks in the board exam; chronic obsession with select careers in medicine, engineering, commerce and management; the colonization of our mental landscape by the notorious chain of coaching centres (the growing suicide rate in Kota symbolizes this pathology); the rat race for improving the ‘ranking’ of a college/university through the mythology of ‘placements and salary packages’, or the ritualization of soulless seminars/publications/conferences. As a teacher, I have always felt that even though the obstacles are enormous, this sickness has to be fought, and we ought to radiate the spirit of a new sensitivity towards education. I have no hesitation in saying that in my art of resistance I engage in a dialogue with a spectrum of thinkers and educationists—say, Rabindranath Tagore’s plea for aesthetically enriched holistic education that unites brain and heart, science and poetry, man and nature, and sees beyond merely technical/instrumental learning. Likewise, the Brazilian educationist Paulo Freire influenced me deeply. For Freire, education is not a monologue; children are not empty vessels; meaningful education is essentially a dialogue, a communion. And it is a kind of critical pedagogy that enables the student and the teacher to work together, problematize the taken-for-granted world, and strive for collective liberation from all sorts of domination. In fact, in this ceaseless quest for a meaningful and life-affirming education, I have often derived my inspiration from Jiddu Krishnamurti. In a way, I have no problem in walking with Tagore, Freire and Krishnamurti because I am not following any particular ‘ism’. And I believe Krishnamurti would have liked this process of ‘deconditioning’ the mind. Anyway, let me come back to Krishnamurti. What a profound insight! Imagine the gravity of the kind of questions he posed. Is education only about learning Physics, Mathematics, History, or a specialized academic discipline? Is education only about passing exams, and getting jobs? It is sad that these days it is becoming exceedingly difficult to find parents, students and even teachers asking the kind of questions Krishnamurti raised. Yes, Krishnamurti, we know, often asked young learners or their teachers: Do you watch the sunset in the valley? Did you listen to the bird’s song with absolute care and mindfulness?

Look at nature, the mango trees in bloom, and listen to the birds early in the morning and late in the evening. See the clear sky, the stars, how marvelously the sun sets behind these hills. See all the colours, the light on the leaves, the beauty of the land, the rich earth. Then having seen that and seen what the world is, with all its brutality, violence, ugliness, what are you going to do?

Of course, in the tiny cells of the hostels in the Kota factory, neither the young aspirants nor their ‘Physics/Mathematics gurus’ bother to ask these fundamental questions. But then, all those who strive for a truly meaningful and liberating education must ask these questions. Watching a sunset, or listening to the bird’s song is not daydreaming; it is essentially about awareness, meditative observation, mindfulness, sensitivity to life and nature, and cultivation of all the faculties of learning. Krishnamurti, as I understand, is not denying the signification of academic knowledge; but then, he is urging us to see beyond, go deeper, and urging us not to be fitted into a violent society, but to create a new humanity.

What is the point of passing examinations and getting degrees? Is it to get married, get a job, and settle down in life as millions and millions of people do? Are you going to allow your parents, society, to dictate to you so that you become part of the stream of society? Real education means that your mind, not only is capable of being excellent in mathematics, geography and history, but also can never, under any circumstances, be drawn into the stream of society. Because that stream which you call living, is very corrupt, is immoral, is violent, is greedy.

Likewise, for a second, let us think of what we are doing in the name of discipline, punishment and surveillance. It causes regimentation, or to use Michel Foucault’s words, transforms a person into a docile body, breeds reckless uniformity, or some sort of militarization of consciousness, and generates artificial order based on fear. Do we want our schools to be transformed into some kind of prisons? Do we want our children to look like ‘disciplined’ soldiers? Do we want our headmasters to behave like army generals? Or. do we want freedom—freedom not as irresponsibility, but freedom as the cultivation of awakened consciousness that generates love, empathy, art of listening, ethic of care and responsibility to others? As I understand Krishnamurti, I feel he was essentially trying to redefine discipline, overcome the psychology of fear, and generating a sense of order based on freedom and responsibility. To me, this vision is remarkable. Let me quote him:

You know, soldiers all over the world are drilled everyday, they are told what to do, to walk in line. They obey orders implicitly without thinking. When you are told what to do, what to think, to obey, to follow, do you know what it does to you? Your mind becomes dull, it loses its initiative, its quickness. This external, outward imposition of discipline makes the mind stupid, it makes you conform, it makes you imitate. But if you discipline yourself by watching, listening, being considerate, being very thoughtful—out of that watchfulness, that listening, that consideration for others, comes order. Where there is order, there is always freedom.

Sometimes, I worry about what is damaging the entire process of growing up of our children through the violence implicit in constant comparison and ranking. For instance, I love music; but my teachers/parents constantly tell me that music would not give me bread and butter; I have to be like the ‘topper’ in my class who is sure to crack the IIT JEE . This is violence—psychic and symbolic violence. And this violence is being perpetuated everyday in our schools, classrooms and families. To borrow Krishnamurti’s words:

When you compare yourself with somebody else, that somebody else is more important than you. Is it not so? You as an individual with your capacities, with your tendencies, with your difficulties, with your problems, with your being, are not important, and so you, as a being, are pushed aside and you are left struggling to become like somebody else. In that struggle is born envy, fear…

Krishnamurti urges us to interrogate the pathology of this ‘normalcy’, and create a culture of education that seeks to tap the unique aptitude and talent of each child. Don’t see it as a dream. We need to strive for it. Isn’t it pathological that thee days almost every child who opts for the science stream wants to become a computer engineer? This uniformity of aspirations indicates the terribly poor psychic health of our society and education.

As I know through important writings/research works on the culture of Krishnamurti Foundation schools, it seems these centres are trying to nurture a flower in a desert, sensitize students, teachers and parents, and create a new generation— creative, sensitive, empathic and compassionate. Of course, as a teacher, I continually ask myself: how do we take this pedagogic experimentation beyond the select enclaves of the Krishnamurti Fundation schools, and try to implement it in altogether different settings—say, a municipality school in Delhi, a rural school in Bihar, or even a fancy ‘international’ school in the posh locality of Gurugram? Even though I have no immediate answer to this difficult question, I continue to keep this question alive.

Deconditioning in the Age of Violence

Now let me refer to yet another issue. I refer to this issue, even if it sounds somewhat political. The reason is that we cannot converse with an extraordinarily sensitive seeker like Krishnamurti in a state of void. We are also historically embedded beings; and the larger socio-political context affects us. Think of the times we are living in. Think of the violence all around us—violence in the name of a fixed ‘ism’ or an ‘identity’. For instance, these days in order to prove my hyper-nationalist aspiration as an ‘Indian’, I must construct my ‘enemies’ with whom I must engage in constant war. And this war is seen everywhere—in media spectacles and television news channels, in cricket matches, in ‘Hindu-Muslim’ binaries, in the temple politics, in mob lynching, in communal hatred. And I have no hesitation in saying that Krishnamurti’s deep insights into the impact of social conditioning on our minds helps us to understand this crisis. When I say I am primarily a ‘Hindu’ or a ‘Muslim’ or a Christian’, or a ‘Indian’ or a ‘Pakistani’, it is because right from my childhood I have been conditioned to believe like this. And it is this accumulated thought or memory that has conditioned me, and caused fragmentation and division. Shouldn’t we bother about the question Krishnamurti raised:

Thought says ‘I am a Catholic, I am a Jew, I am an Arab, I am a Muslim, I am a Christian. Thought has created this division. So thought in its very nature, in its very action, is seen to be divisive, bringing about fragmentation. Do you see that thought must bring about fragmentation not only within yourself, but outwardly?

The result is that we fail to see the world with absolute freshness without any baggage of thought or past memory. The moment I say he is a ‘Muslim’ or a ‘Pakistani’, my conditioned mind begins to equate him with thought or memories—say, the history of Islamic invasion, the trauma of, partition or the politics of terrorism. I fail to see him/her as just humane, or a living presence here and now—with freshness, without any abstract category, without any baggage of the past. This is the breakdown of communication. The resultant violence or division implicit in the process of ‘conditioning’ can be overcome only trough ‘deconditioning’. And this ‘deconditioning’ is possible when I acquire the courage and honesty to see beyond temples, mosques, churches, nationalist borders, political rhetoric, nationalist slogans, and live in the moment without this baggage of memories, and with freedom and freshness. At a time when education is becoming heavily political, the politics of the curriculum is fast moving towards ‘nationalist’ discourses, and those who think differently are harassed, can you and I rediscover Krishnamurti, remind ourselves of the danger of conditioning, and strive for a kind of education that broadens one’s horizon, makes one dialogic, and sees beyond nation, caste and religion? I believe that a nuanced engagement with Krishnamurti has acquired added significance at this crucial moment of political/cultural violence. Indeed, we need a kind of education that helps us to decondition our minds.

Salvation in the Age of Instantaneity

And herein lies the significance of the third issue I am referring to. If we keep our eyes open, we can see the mushrooming growth of ‘spiritual market’. In the age of instantaneity, you can consume anything—be it a cup of Starbucks Coffee or a quick look at a book by Osho in the airport lounge. Even salvation—freedom from worries and anxieties that characterize our existence in this fast and rapidly changing world—can be achieved, if, as the market dictates, you can follow, say, a set of instant packages—a three day retreat in a fancy ashram with the yoga club and breathing exercises; a self-help book written by a techno-friendly ‘guru’ on how to energize your mind; or a YouTube video on diverse techniques of ‘inner engineering;’. These salvation capsules sell in our times when everything has to be consumed instantly. I ask you to wonder whether our inner quest can be accomplished in this way. Likewise, it is important to ask whether any ‘guru’ or organized Church can salvage us. But then, for the crowd—the crowd of followers and consumers—it is easy to surrender in front of a spiritual ‘brand’ or a ‘guru’. It does not require any inner churning from us. Those who are old-fashioned and burdened with ritualism surrender before the priests; and our postmodern consumers seek to find refuge in fancy gurus. However, when we experience Krishnamurti’s deep reflections, we realize that ‘truth is a pathless land’; no guru, no sect, no institutionalized priestcraft, no organized religion can take us to the realm of truth; for a seeker/wanderer, it is a continual journey. I feel tempted to quote from his path-breaking speech :

Organizations cannot make you free. No man from outside can make you free. The key is your own self, and in the purification and in the incorruptibility of that self alone is the Kingdom of Eternity.

But then, for most of us, religion is centred on some fixed doctrine, some fixed holy book, or the rituals sanctified by the priestcraft. And these days we are witnessing what this means—I mean the unholy alliance of the market-driven rationality and religious nationalism. However, If you are a seeker or a wanderer walking through a ‘pathless land’, you cannot exist merely as a ‘Hindu’, a ‘Muslim’, a ‘Buddhist’, a Christian’; nor can you say that everything is there in the Bhagavadgita, the Quran or the New Testament. Well, I am not saying that we should not read these texts; I am not saying that we should not reflect on Buddha or Jesus. Well, I too read Osho, Thich Nhat Hanh or Allan Watts. But then, unless I experience and realize the power of love and compassion, I will only recite Buddha or Jesus as a parrot. My words will be empty. Or, for that matter, if I have not realized the merger of the finite and the infinite in a tiny blue flower, it means nothing even if I become a scholar of the Upanishads. Although psychologically it is more comforting to be a follower of a guru or some organized religion, it is truly challenging, as Krishnamurti repeatedly reminded us, to be a wanderer.

Conclusion

Yes, I am walking, wondering, reflecting… And as a teacher, I am continually learning and unlearning. I do not know whether it is a ‘pathless land’. However, as I feel, I don’t belong to any ‘ism’ or a particular school of thought. Possibly, my dialogic self is possibly trying find Jiddu Krishnamurti as yet another companion –like. say, Rabindranath Tagore, Thich Nhat Hanh, Jalaluddin Rumi, and others. Possibly, Krishnamurti would not have liked had I said that ‘I am his follower’. After all, Krishnamurti himself made it abundantly clear when he said;

I desire those who seek to understand me to be free, not to follow me, not to make out of me a cage which will become a religion, a sect.

I must keep my journey alive even if I need to walk through a ‘pathless land’.

Avijit Pathak taught sociology at JNU for more than three decades. This essay is based on the lecture he delivered at the Krishnamurti Foundation, Chennai on January 26, 2024.