- Dr. Reetamoni Das is Assistant Professor, Amity University, Mumbai.

Films are cultural artifacts that explore various socio-cultural aspects. Women, the depiction of their concerns and stories has always been a problematic issue within this landscape. Amidst controversy of objectification of women and trivialization of these issues has thrived an alternative group of filmmakers whose work we collectively refer to as ‘women’s cinema’.

Women’s cinema has been producing a counter narrative to the mainstream depiction of women’s issue by introducing a narrative that is from the point of view of the women. Women’s cinema tells the stories of the lived experiences of our gender, the physical, emotional and psychological depth of our feelings, and read meanings into our ‘erratic-irrational’ behavior.

Here the woman is not the subject of voyeur; her subjectivity is well preserved and not questioned. We know her story, her fights and her triumphs. We know her battle strategy; we see how popular narrative is subverted.

Kalpana Lajmi’s films not only produced a counter narrative to patriarchal values of story-telling but also gave subversive readings of various gender roles. The women of Lajmi are not goddesses or divine figures they are humane, prone to a gush of emotions. Thus, Priyam’s relationship with her former lover (in Ek Pal) is not evaluated or brought under moral scrutiny. The film distances itself from being judgmental. Priyam’s affair with the other man is not pronounced as sin and she is not dissected for her action.

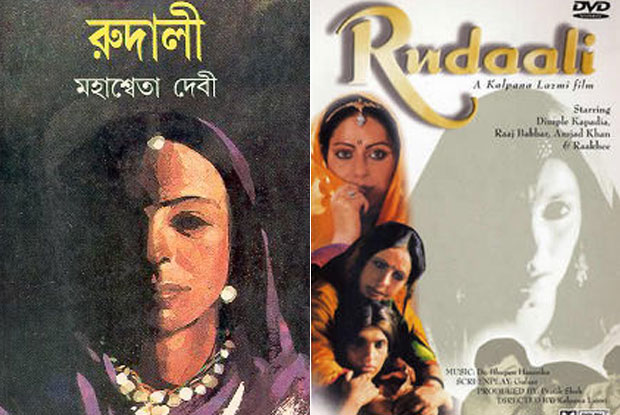

Rudaali sealed her name in the list of seminal filmmakers of all time. This adaptation of Mahashweta Devi’s novel of the same name shone in the National Film Awards and was India’s official entry for the Best Film in a Foreign Language at the 66th Academy Awards. The film narrates the tale of exploitation and poverty, and intertwined therein is the narrative of women. Her gender when blended with the oppressive system of caste and class relegates her to the margins of deprivation. She however turns the system around and writes her own tale, when her gender and her position become her tool. Taught by her allegorical (and real) mother, the protagonist Sanichari dons the role she was destined to play, but fully aware of the system that runs it. She arrives at the consciousness where the very role that she is destined to play becomes her instrument for her survival (triumph).

Society’s reluctance to crossover the binaries of gender has been the theme of many films. Lajmi in her film Darmiyaan depicts the identity crisis that Immi faces from childhood to his youth. Immi’s struggle in negotiating both the public and domestic space takes a big part of the plot. While societal discrimination and exploitation keeps him confined to the domestic space, the environment of denial regarding his identity at home keeps Immi in a continuous state of oscillation between the two spaces, unable to find a personal space in either. Immi’s conflict comes to resolution on screen space with his decision to adopt the abandoned child and bring it up as his own without prejudice. While Immi is at the crossroads of gender, Zeenat, Immi’s mother is in the dilemma of bidding adieu to her waning career. Zennat’s depleting value as an actor with fading beauty can be read as Lajmi’s comment of the lust for ephemeral beauty and pursuit to produce voyeuristic scophophilic pleasure on the screen using the female form.

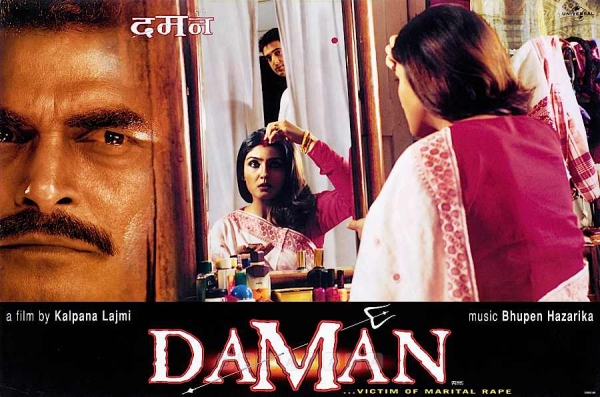

Lajmi’s heroines not only rise above the image of weak, but reverse the course of action. Durga in Daman rises to the stature of her proverbial namesake and demolish the one that used to dominate her. The film is a dramatic creation to portray the horrors of domestic violence. The metamorphosis of the protagonist is a journey of self-realization where she evolves from the weak and submissive belle to the persona of the Goddess after who she is named. The film also dwells into the trajectory of marital rape, an issue that is seldom discussed within the cinematic space. Lajmi is not afraid to ask the uncomfortable question in her films; her films are a stance that she takes as a woman.

The propaganda of highlighting concerns of women through her films remains foremost in Chingaari as well. Here is a comment on the extreme positioning of women in society, one as a Goddess and other as a prostitute. Once again, the nexus of social hierarchy, patriarchal politics and religion to undermine the position of women in society forms the larger plot of the film. In Chingaari it is neither the fearsome priest nor the benevolent lover that provokes Basanti; it is the maternal passion, the bonding with her child that empowers her. Lajmi do not read motherhood as an impediment but as a celebration and an experience which would not belittle the self but express it in multifarious ways. The yearning for the child—in Rudaali, the protagonist’s pain of separation from her mother, in Ek Pal Priyam’s denial to let the unborn and in Daman Durga’s decision to overcome her demon-is a recurring motif in all her films.

While there have been efforts for positive portrayal of women on screen, the layered narrative however has much to achieve to narrow the gender gap. There have been attempts in films to champion the cause of women’s right to their bodies and sexual freedom. The debate, though, is not just about talking about women’s rights or issues. It is about giving them the power to transform their lives. Unfortunately, many films, while trying to positively portray women, fall into trap of losing the idea in the layers of the narrative that brings forth a (strong) male deliverer guiding them on the journey to emancipation or empowerment.

Lajmi’s heroines triumph here. They write their own story and are on the road to self-discovery and self-determination. They do not need validation from an external source to justify their actions, if any they stand in solidarity with their mothers and sisters who have gone through the same ordeal as them. These finer strands of cinematic narrative, as seen in Lajmi, have also been dealt in by other women filmmakers like Aparna Sen, Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta, Leena Yadav, Gauri Shinde and Alankrita Srivastava. Their films and the narrative woven into the cinematic aesthetic give us reasons to believe that the film industry needs more of such filmmakers with an alternative voice that would speak in diverse languages and tell a tale that has been so far unsaid.