EDUCATION

As the anxiety over children’s admission into nursery classes becomes infectious, the author appeals to the parents to reflect on the ‘goodness’ of ‘good’ schools.

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]nce again we are witnessing the typical parental anxiety. Their children ought to undertake a new journey – from home to school. And when the process of admission into nursery classes has begun, they are anxious, worried and tensed. Will their children manage to get admission into select ‘good’ schools? Or for that matter, should they send their applications to as many schools as possible? Indeed, running around schools, meeting the Principals or trying to find some other avenues for getting the admission – it is not a relaxed time for the parents.

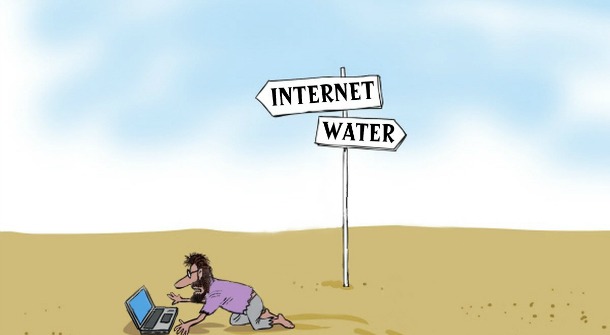

Yes, it is sad. In a sane society there should not be any anxiety for children’s admission into schools. One should also expect that all schools have sufficient legitimacy, and are capable of providing meaningful/life-affirming education. However, as, because of the lack of political will, government schools begin to collapse, private schools with all sorts of promises and packages attract the aspiring class. Moreover, in an over-populated country like ours, the act of living is always an experience of scarcity. A fear of lagging behind or missing something vital characterizes our existence.

In an age in which ‘brand consciousness’ invades our mental landscape, we begin to run after select ‘top’ schools. These schools with their characteristic arrogance make the parents feel that things are not easy. I know an Assistant Professor in the University of Delhi. At the time of her child’s admission into one of these schools she was asked by the Principal:’Tell me what sort of research methodology you used for your Doctoral thesis.’ One really doesn’t know whether there is an organic connection between the child’s activity in the nursery class and her mother’s Ph. D work.

The arrogance of ‘good’ schools, the ‘aura’ surrounding the fancy Principals, the mystery of the ‘management quota’, and the anxiety-ridden parents caught into a war front–our education is in deep crisis.

‘Good’ schools: learning to be consumers

To begin with, let me reflect on the goodness of ‘good’ schools the parents are searching for. You need not be a social philosopher to understand this. Quite early in the morning–just go for a walk, and keep your eyes open. You are bound to notice how a recklessly stratified/hierarchical society functions. There are fancy air-conditioned buses taking well-dressed/English-speaking children to those ‘top’ international schools (the word ‘international’ has its magical power in the era of globalization); there are middle class parents waiting with their kids (in clean school uniform carrying colorful bags and water bottles) to send them to moderately ‘successful’ schools; and then you see the children of the poor, the marginalized and the lower middle class with torn clothes or not so fancy uniform walking towards municipality schools. In a way, you see the dynamics of class and social/cultural capital in the choice of schools.

Is it then that in all these ‘good’ schools one is further learning the values, aspirations and other traits of the privileged class? Well, it is always possible to say that one learns English and History, Physics and Geography, and computer and clay modelling. One learns (particularly because of the rigorous ritual of weekly tests, summer/winter projects, and periodical workshops with counselors) how to be ‘successful’ in life. However, it would be wrong to say that these schools exist only for scoring 99 percent in the board examination. Even Kendriya Vidyalayas and some ‘Hindi-medium’ schools can do that.

Take two illustrations. In these ‘top’ schools children learn and cultivate a set of ‘class traits’ that distinguish them from the ‘ordinary’ – say, the marginalization of Hindi because French has to be learned; the proximity with some sort of English ‘pop culture’ (jokes, music, thriller, comic books, cartoons and films) and resultant distance from the ‘vernacular’ traditions; and all sorts of ‘exchange programs’ that make them ‘global’, not ‘local’. Likewise, these schools serve yet another function; they teach children the first lesson of consumption – the ‘thrill’ of being a consumer. What is popularly known as ‘school fest’ is essentially a market-driven space. The flow of money is assured, and with ambitious (or compelled by the logic of conformity to the system) parents children love to buy and consume, and eat and waste.

The fact is that ‘good’ schools exist to reproduce social inequality, serve the interests of the privileged classes, and separate their ‘products’ from the ‘ordinariness’ of everyday life.

Seeing beyond costly ‘alternatives’

Are the parents searching for these ‘good’ schools? Is this race merely for transforming their children into reckless aspirants for ‘success’ (measured in terms of money, possession and distinctive cultural markers), and consumers of all sorts of material and symbolic goods? Or is it possible for them to strive for something else – a new form of learning based on love and creativity, connectedness and reciprocity, and knowledge and awakening?

Yes, I am aware that this ‘alternative’ quest is difficult for two reasons. First, the dominant values are so deeply intenalized that anything that is different is seen as either ‘foolish’ or ‘risky’. A ‘romantic’ Tagore, an ‘impractical’ Gandhi, a ‘leftist’ Paulo Freire – we negate all critical voices and alternative aspirations for a mode of education that seeks to bring the child closer to nature, integrate ‘work’ and ‘play’, or ‘mental’ and ‘manual’, assert the critical potential in a dialogic interaction, and strive for an integrated personality – not an atomized competitor running ceaselessly without a pause, and striving for a mythical success.

Second, in our times when the elites appropriate everything, even ‘alternatives’ lose their meaning. It is not easy to afford this sort of ‘alternative’ education. Jiddu Krishnamurti was great; so was Sri Aurobindo. Yet, Mirambika (a school supposedly based on ‘free progress education’), or Rishi Valley School (a project dear to the followers of Jiddu Krishnamurti) exists as a solitary island; not everyone can afford it. ‘Alternatives’ are really becoming costly!

Yet, I would argue that despite these constraints, the parents should not stop reflecting on the following:

(a) There are limits to what schools can do. In fact, real learning happens outside schools. Seeing an amazing sunset from the balcony, walking with the old grandmother in a lonely afternoon, cooking simple rice and dal for mother and giving rest to her, and reading a poem or a story just for joy–money cannot buy these intensely enchanting experiences which transcend the binaries of ‘success’ and ‘failure’. And this doesn’t require ‘international’ schools; this needs only the willingness on the part of the parents to live with children, communicate with them, sensitize them, and not to depend for everything on private tutors, technological solutions and career counselors.

[irp posts=”7752″ name=”Isha Ambani’s Wedding and Our Collective Decadence “]

(b) Life has a meaning, a higher purpose. One is not born only to become a chartered accountant, a corporate professional, or a lawyer. As we begin to impose these socially constructed notions of ‘success’ on children, we cause a great damage to them. Is it the end of innocence and all dreams? As a two-year-old child goes to a ‘play’ school and remains outside home for a considerable amount of time, is she learning the first lesson of living like a ‘disciplined’/’regimented’ worker? Or as coaching centres, guide books and all sorts of ‘success mantras’ begin to replace Munshi Premchand and Rabindranath Tagore, and spontaneous football and kite flying, we destroy a possibility. Anxiety-ridden, perpetually restless, aggressive and alcoholic: is it what a ‘successful’ person is supposed to be?

Dear parents, are you thinking?