Aggarwal, Suman Khanna. 2020. The Science of Peace. New Delhi: Shanti Sahyog Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

Words and images on a mobile screen these days are enough to drive us into a fury. Casual comments by friends enrage us and we want to immediately hit the “unfriend” button. In times like these it is good to come across a book that reminds us of an old Indian way of confronting what we think is evil with firmness but with love. It offers an alternative to dealing with wrongdoing than just turning away or hurling abuses at each other.

There has long been a culture of war and violence which makes it manly and fun to attack one’s neighbours. But there have also developed several examples over the last century of peaceful methods for addressing conflicts and injustices. A vibrant pacifist movement had emerged during and after the first world war in Europe and North America. It opposed the madness of killing millions of people for nationalism and empire-building. After the second world war killed even more millions the United Nations was set up as a powerful institution to promote peacemaking all over the world. It often failed in its goals, but its emergence has been unprecedented in human history. The UN anchors today many educational and interventional initiatives in peacebuilding. There are several more of these voices which speak of compassion and dialogue as the way to decide conflicts. Among their greatest examples is the Civil Rights campaign of USA, which opposed racism by consciously training its activists to endure blows, being spat at and being abused. One of their milestone moments was when their Montgomery protest was televised nationwide. Black youths walked into eating places where their entry had been banned and occupied seats there. White audiences saw on television the calmness with which they sat and faced white attackers trying to push them out and something melted within many of them. This was a turning point which convinced the American establishment to stand up against racism.

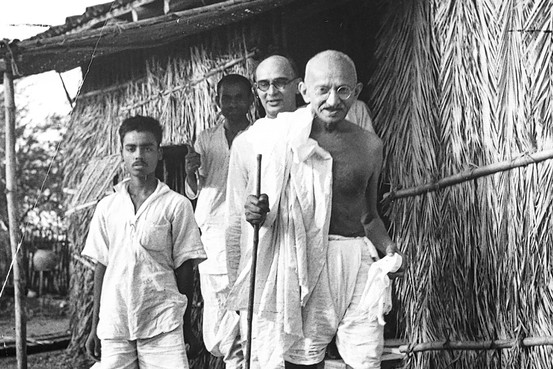

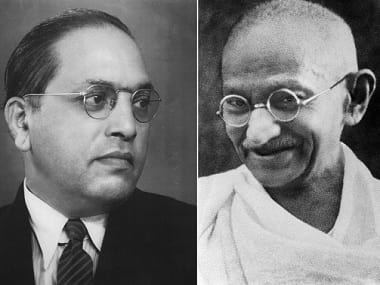

Gandhian non-violent movements have been an important thread shining through this history of peaceful oppositions to injustice. Shantha Khanna Aggarwal’s book The Science of Peace is a short, simple introduction to Gandhian ways of struggling against what we think are profoundly wrong acts and policies. It presents a mix of the essential techniques of Gandhian politics with more contemporary work on the resolution of various kinds of conflicts.

The book argues that conflicts are everywhere – between neighbours, spouses, communities, nations, indeed within our very hearts. If something is as ubiquitous as conflict, then one need not fret about its existence. The issue is really not that conflict is present, but how it is dealt with. Aggarwal believes the use of violence to handle and resolve conflicts is indefensible. Violence itself, of course, can be of many kinds, of which physical violence is only one. There is the structural violence of poverty, the cultural violence of gender and the many kinds of mental and spiritual violences that we encounter at every turn. There are deeply entrenched forces, she says, which promote violence and war. Their power and resilience should not be underestimated.

Aggarwal believes Gandhian nonviolence offers an equally powerful counter-balance to the ubiquity of violence. She claims that where violence is the “law” for animals, non-violence is the moral “law” which humans should follow. Non-violence is a “science” for her – it calls for experimentation and is a systematic body of knowledge. It can be applied to help solve human problems. She believes non-violence deserves to be taught in schools and colleges the way other school subjects are taught. Violence has become banal, she reminds us. It is everywhere and a routine part of our lives. In an delightful play on Hannah Arendt’s thesis of the banality of violence, Aggarwal says we need to create a banality of non-violence, making it as ubiquitous and effortless as violence is today. It must be promoted through education and popular culture.

What is non-violence? It is a holding back from violence, but not just that. Not doing violence would only be a negative definition. There is a positive aspect to non-violence, too. It is caring for all beings, even the unjust ones. It is wanting their flourishing, as well, not just one’s own flourishing. That is why the unjust and the oppressive must be cured of their evil habits – it is for their own good.

Aggarwal points out how close non-violence is to love: it makes the other’s desires and wishes one’s own. It refuses to take advantage of the other’s weaknesses and is always willing to sacrifice oneself. All efforts are made to build a better relationship with others. When one discovers that they are doing something wrong we act not out of hatred and repulsion, but out of love. By reaching out in friendship and compassion the non-violent actor can help the oppressors to discover their wrongdoings and rise to become their better selves. The non-violent person is acutely aware of their own shortcomings and failings. So the oppressor is not humiliated when they acknowledge their oppression. Aggarwal’s interpretation of non-violence says it will embrace the oppressor as a fellow sinner and pray for their together rising above their respective sins. The practitioners of non-violence must work not just on their “opponent”, but upon themselves too. Intense reflection and continuous cleansing of the self was a hallmark of Gandhi’s approach to non-violence.

For believers in non-violence like Aggarwal, it must be practiced irrespective of whether it appears to be working or not. She argues alongside Gandhi that good things cannot be created by evil means. Non-violence is the necessary means for us if we want to create a just and compassionate world. There is no other way to achieve that end.

Non-violence is intimately interwoven with the idea of truth itself, according to Gandhians. Truth is said to be standing beyond our individual ways of seeing it. The metaphor of the blind men trying to touch an elephant at different points and understand its nature is a favourite here. Moral truths can have an objective reality she believes, but we as humans will always be limited in our ability to grasp them, since one person is touching the tail while another is touching the tusks. Such an understanding of our limited ability to grasp the truth is the basis for non-violence. If no one person can have the full truth, then there can be no grounds for using violence to force our views on others.

At the same time Aggarwal believes there are non-violent ways of pressing one’s opposition to wrongdoing. The idea of satyagraha is a celebrated Gandhian approach to pushing a recalcitrant and overwhelmingly powerful colonial state into changing its policies. Gandhi believed in taking a carefully thought out moral-cum-political stand. Satyagraha literally meant firmly pleading with those who were mistaken (in Gandhi’s opinion) to see the truth. If necessary this could even mean making sacrifices so that so that the evildoers were stunned into paying attention. In a fascinating chapter Aggarwal sketches out the celebrated Salt Satyagraha as a classic example of non-violent anti-colonial struggle. She brings out all the shrewed political planning and careful building up of public opionion which went into it. Gandhi declared that he was giving time till the end of his march to Dandi for the British to realize their folly in taxing salt. This was designed to mount a rising crescendo of moral pressure on the British as well as increase their worries over what would happen if millions broke their laws. Equally carefully planned was the training and cultivation of moral strength in the volunteers who participated in the movement. That strength permitted hundred of people to accept skull-splitting blows from the British without retaliating. Aggarwal makes the point quite well that non-violence is neither passivity nor acceptance of wrongdoing. It can be an active struggle for the overturning of immoral policies.

Where did this ability to stand up against the might of the largest empire in the world come from? Aggarwal says it came from a source Gandhi understood and was able to connect with – the power which comes from love of the people. Empires and modern states usually understand only the power of the gun or of wealth or of bureaucracies. Gandhi understood another kind of power, that which comes from empowering people. The word “power” she reminds us, does not mean only the control of others to achieve what one desires. It also means control over one’s self to achieve what one desires. The power of non-violence is difficult for those used only to state directed violence to understand. She says millions were drawn to Gandhi because they sensed his love for them. Through this love he helped them look into themselves and become better persons than they had been. Gandhi gave people a sense of control over their own lives and selves. This became the basis of an incredible consolidation of people’s power, which turned out to eventually be more than the British colonialists could suppress.

Gandhi died three generations ago, slain by a group of upper-caste Hindu men who were unable to resolve the angers within themselves. They mistakenly thought that by focusing on killing him there would be some relief to their angst and misery. In spite of all the years that have passed since then, Aggarwal believes that Gandhi’s path to non-violence is still relevant. She believes that building organizations and armies of the non-violent is the answer to the grave threat humanity faces in these troubled times. She finds in the Shanti Sena an example of such a non-violent force – a trained group of people who are skilled in mediating and do regular developmental work, but can step in to calm things down whenever there is an outbreak of communal violence. These would be people who would work as peace builders, peace makers and peace keepers. Is this just another nostalgic dream of aging Gandhians? She argues that it is completely viable, reeling out name after name of organizations and movements which have tried the non-violent path, from Peace Brigade International to Khudai Khidmatgars. They have been several times more successful than movements which took to the methods of violence, she points out.

Aggarwal’s book presents systematically the main principles of Gandhian non-violence and provides examples that help us to see what they mean in practice. As an introductory book it has no choice but to simplify things and to leave out many detailed arguments and justifications. At the same time the theme itself challenges so many of our conventionally held beliefs and is so provocative that several questions arise.

One question is regarding the certainty of one’s beliefs and positions. The idea of dialogue means that one is always open to other points of view and to reconsidering one’s own views. While the book emphasizes peaceful ways of trying to persuade others, it is not clear what methods will be used for a dialogue with them. Non-violence emerges as a way to change others, not necessarily to listen to them. This difficulty is echoed by the use of terms like “science” and “law” for the ways of peace. These suggest a great moral and empirical confidence in them. However many decades of debate over science and the laws of human behaviour have made us now much humbler about claims to law-like certainty or to the finality of of scientific knowledge.

Often Aggarwal states principles and beliefs in an assertive manner without fully discussing or justifying them. Take for instance the position that one should stick to non-violence even if it is not working. This is what philosophers call a deontological ethics, where one practices a virtue irrespective of its consequences. Why should one do this? We are not enlightened on why after all one should consider non-violence as something that should be practiced without thought for its consequences. Why not look for consequences and use them as the basis of choosing what to do nor not to do? We could also have argued that non-violence has excellent consequences which people have not cared to pay attention to. Why insist on nonviolence even in situations where it obviously leads nowhere? Perhaps there is a compelling reason to do so. But Aggarwal does not shed enough light on that.

Another question is that of whether moral arguments and pressures are sufficient for non-violence to prevail. The description and analysis of the Salt March shows a superb grasp of the realpolitiks of satyagraha. Gandhi is seen to rely not just on moral arguments, but also on shrewd political moves. Indeed he does not seem to be making great efforts at dialogue at all. He is instead building a public and media pressure which embarresses and confuses the British government. Scholars like Bhikhu Parekh have argued that non-violence was a mix of morality and politics, with Gandhi emphasizing the first and his opponents pointing to his use of the second. Could it be that non-violence’s self-image as a purely moral act is incorrect? Perhaps non-violence does not prevail because an all encompassing divine truth speaks through it. Or at least not just because of that. Maybe a better way of understanding non-violence is that it creates social and political conditions where people become willing to listen to each other. It can be argued that non-violence, compassion and dialogue work only in certain conditions and not in others. When there is too great an imbalance of power, when people have very different moral ideas of what is wrong and right, when they cannot understand each other, dialogue and compassion will fail to create better solutions. If we believe that non-violence is the way to create a better world, part of the struggle must be to create those conditions where it can be effective. We must build a sociological, pschological and political theory of non-violence, not just a spiritual one.

The book could have done with some more careful editing. The specific examples which Aggarwal gives also leave one wanting more. The book speaks at a level which international audiences would relate to the best – war, conflicts between countries, disarmament. These are important of course. But in today’s India the immediate challenges which non-violence must face up to are different – a national politics that relies more and more on fake news and smearing, a caste system that humiliates and excludes while pretending that it no longer exists, growing resistance to patriarchy and increasing public violence to assert it again, soaring inequalities between the politically connected, industrialists, managers and the rest of India, the daily humiliation and silencing many communities must face and so on. Aggarwal’s approach to peace as the path to justice touches upon these only in passing. The uses and relevance of non-violent approaches to create dialogue, transformation and justice in a time when dissent is being hammered and jailed remain unexplored and untalked about.

For all this, Aggarwal’s short introduction to peace is a cogent introduction to Gandhian non-violence. It reminds us that the power of love is usually forgotten and overlooked. It is actually present everywhere and in the form of social solidarity it is the implicit force behind all social and political mobilization. The book invites us to see human affection and respect in a more systematic way and to start visualizing ways of getting justice that build upon these rather than upon fear, temptation and hatred.

Professor Amman Madan teaches at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India.