Even though I see an artist beyond the politics of ‘awards and prizes’, the fact that this year the prestigious Dada Saheb Phalke award would be given to Amitabh Bchchan has made me think of his craft and performance once again.

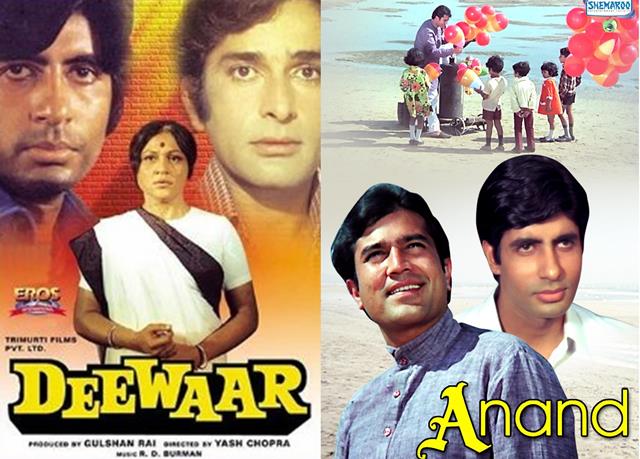

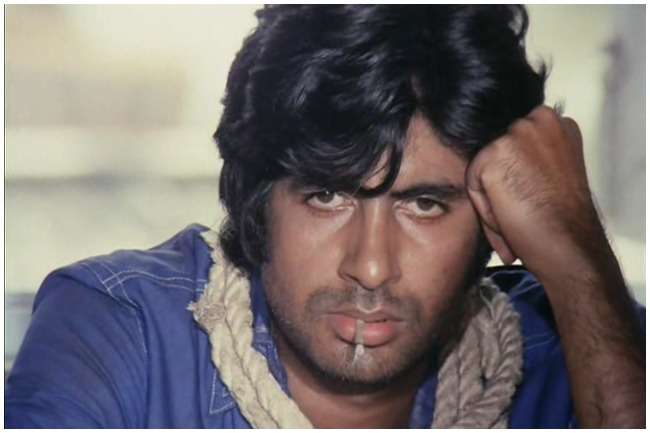

It would not be wrong to say that my generation loved Amitabh Bachchan. As I recall, it was in 1975 that I saw Deewaar in a cinema hall in north Kolkata. Amitabh as Vijay possessed me. I liked his intensity; I felt the pain of his tormented self – his anger, his traumatic memory of childhood, his psychic/emotional separation from his father, and his reckless urge to defeat the system at its own game. I saw his anger as well as his love – his intense attachment to his mother, and simultaneous separation anxiety when, because of his misdirected path, his mother boycotted him, and chose to live with his younger brother – Shashi Kapoor– the honest police officer. His passionate engagement with Anita (Parveen Babi), her murder by the team of the opponent gangster, and eventually his union with his mother (Nirupa Roy as the archetype mother in the film industry) in the temple at the time of his death: yes, Amitabh Bachchan – with his body language, delivery of dialogues, and the intensity of the facial expression – entered our consciousness.

As college students growing up in the turbulent 1970s, we used to wait for his films. And Amitabh’s intensity would continue to charm us – in Zanjeer, in Sholay, and in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar. Even the way he died in his films, I felt, was remarkable. He died in Deewaar; it was like entering the mother’s womb, and becoming free from all tensions and anxieties after passing through a tormented journey in life. Both in Sholay and Muqaddar Ka Sikandar , his death also reflected his pain, melancholy and love – possibly, an element of sacrifice conveying a message to Veeru (Dharmendra) and Vishal (Vinod Khanna). Possibly, his appeal was that he protrayed yet another image of a ‘hero’ – not the sweet/romantic one continually dancing with the beloved under the tree; but a tormented being traumatized by childhood memory, and psychologically affected by a problematic relationship with his father (from Deewaar to Trishul to Shakti), angry with the falsehood and corruption implicit in the system (Zanjeer), and often misunderstood (see the way Raakhee could never understand his love for her in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar ). Even in his love there was a sense of loss and pain. Anita (Parveen Babi) was murdered in Deewaar; even though Rekha as the ‘other’ woman with her dance and music sought to heal the wound of misunderstood, angry and alcoholic Amtiabh in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar, everything ended in a tragic note. And his longing for Jaya Bhaduri in Sholay–often poetic, not explicitly stated, and communicated in silence–could not reach its ultimate destination because he died. In the post-Rajesh Khanna era, he gave us yet another notion of being a Bollywood hero. And we consumed him. Was it because there was anger, pain and psychic restlessness in the epoch?

Did the stardom enslave a potentially good artist?

But then, with the status of being a mega star with immense popularity and mass appeal, did he eventually become a ‘shahenshah’ of the film industry–pampered by the likes of Yash Chopra, Prakash Mehra, Ramesh Sippy, Tinnu Anand and Manmohan Desai? Did this complete merger with the industry – its mainstream narratives, its glitz, glamour and money–prevent him from articulating his talent and creative skill of acting in more meaningful ways? I often ask this question. Because in the same period when Amitabh was immensely powerful on the screen, we saw some other possibilities–say, the actors like Amol Palekar and Farooq Shaikh becoming closer to our normal/middle class/everyday existence, and the lyrical softness in the low budget films like Rajnigandha, Chitchor, Sath Sath and Baton Baton Mein giving us the necessary relief from the hyper-real deeds of the ‘Don’ and his magical play with glamorous Zeenat Aman, or the somewhat comic performance of Anthony Gonsalves, and his romance with Jenny (Parveen Babi) in Amar, Akbar Anthony. Was it that Amitabh Bachchan became a victim of his own stardom, and made him inaccessible to those who wanted to make more life-centric films?

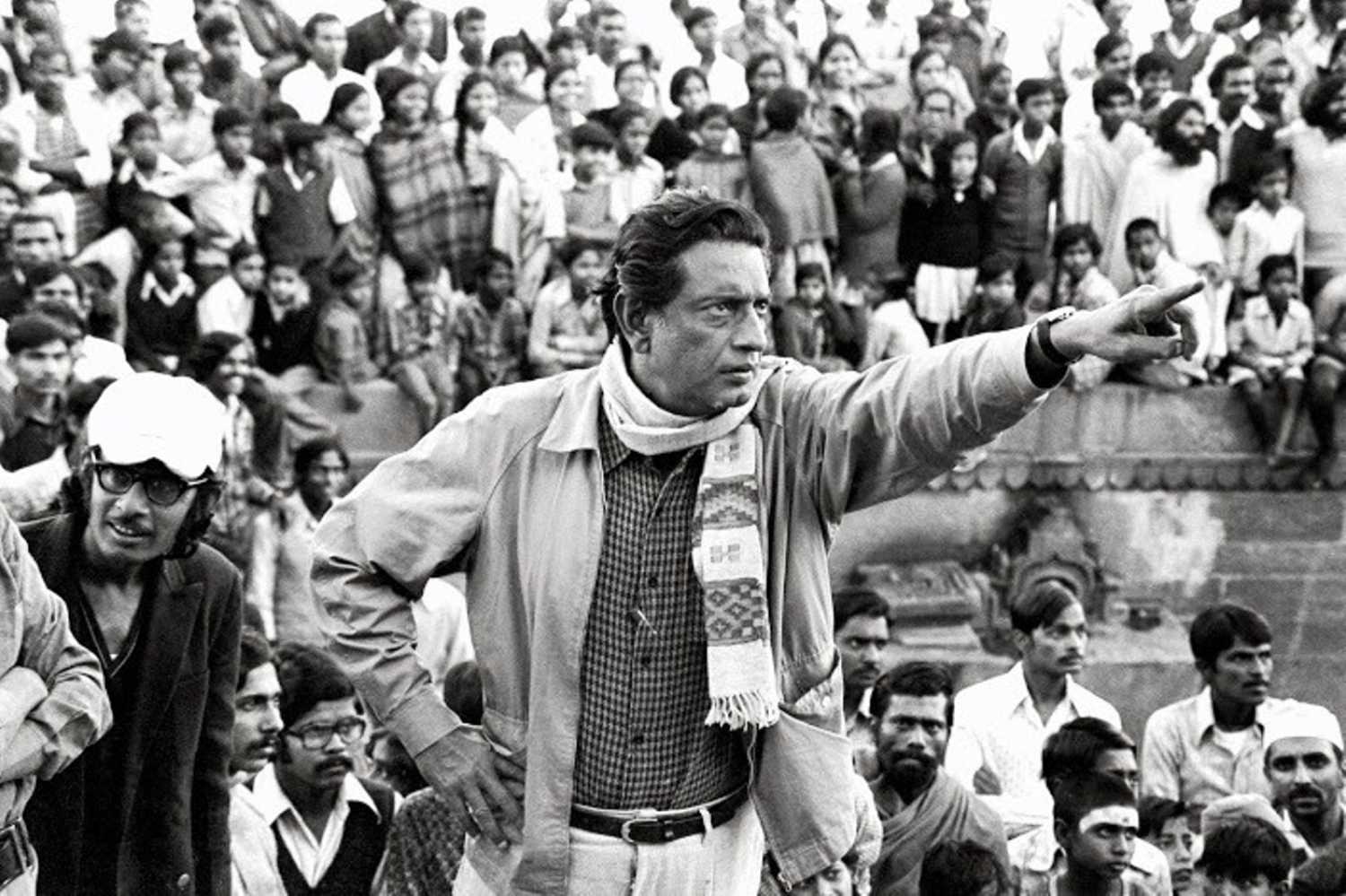

Sometimes, I wonder why he missed the sort of films that gave us a superb actor like Om Puri (what an amazing performance in Govind Nihalini’s Ardh Satya), or say, Naseeruddin Shah( be it Shyam Benegal’s Manthan or Govind Nihalini’s Aakrosh). I also ask myself why Amitabh could not become an integral part of yet another creative endeavour made by the directors like Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. Well, I am not here to engage in an act of comparison. Every artist, I admit, is unique. And I believe that Amitabh Bachchan, despite his stardom and performance in mainstream/commercial films, is also a great actor. However, his potential, I fear, was not wholly tapped by the industry. Or, possibly, his stardom proved to be an obstacle.

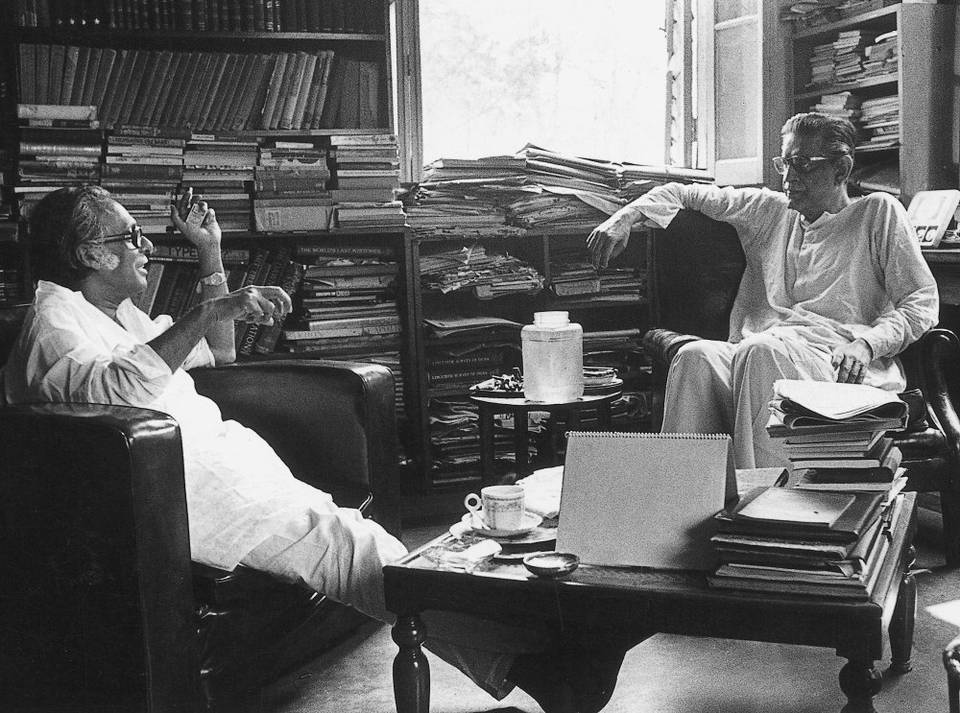

Well, I also know that Amitabh was lucky to find a director like Hrishikesh Mukherjee who could add some deeper meaning to otherwise popular films. Even though Rajesh Khanna was superb in Mukherjee’s Anand, I loved the role and performance of Bachchan. As a young doctor, his friendship with Rajesh Khanna, and the intensity of his pain as Khanna–a cancer patient–was eventually entering the domain of death also helped the film to reach a great height.Yes, Mukherjee made it possible for him to act in immensely sensitive films like Abhiman and Mili. No, it was not the Amitabh of Deewaar or Zanjeer; here Amitabh was humane, emotionally vulnerable and at times, psychologically insecure. And I feel that Jaya Bhaduri – with her feminine grace and the treasure of the inner world–must have made the mega star realize that the ‘angry’ (or ‘patriarchal’?) young man ought to learn a couple of lessons of the meaning of the subtle art of acting from her.

Did the ‘angry’ man eventually become a victim of the comfort zone?

I have no hesitation in saying that Bachchan continues to surprise us with his immense life-energy and creative skills. I am happy that eventually he came to terms with the natural and beautiful process of ageing. I am also happy that some innovative directors imagined the appropriate roles for him. Prakash Jha’s Aarakshan was promising; Amitabh proved himself in Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Eklavya, and in R.Balki’s Paa he dared to experiment with himself with the role of the 12-year-old child suffering from rare genetic disorder. Yes, he was great in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black; the role of a cretive and determined pedagogue engaging with ‘deaf and blind’ Rani Mukherjee was path-breaking; and in Shoojit Sircar’s Piku, we saw Amitabh as an old/retired Bengali gentleman obsessed with disease and chronic stomach disorder, and heavily dependent on his daughter (Deepika Padukone). Yes, in the film he died once again after a rhythmic bicycle ride in his own city Kolkata. Wiith this meaningful death, we felt the power of his performance once again. From the fight scene in Deewaar to his frail/sick body in Piku: Bachchan as an actor evolved. The journey of life with its ups and downs, I assume, taught him many lessons.

Yet, sometimes I feel that he could have done something more meaningful; he could have crossed the safe zone of the cycle of stardom and blockbusters. I love Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor; in their films I see an ernest zeal for experimentation, a philosophy, a worldview, and a blend of enchanting music and cinematic art. Neither Deewaar nor Khabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham would make me feel what Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool or Raj Kapoor’s Awaara does to my consciousness.

Well, I know that Bachchan came closer to the new generation with the television show Kaun Banega Crorepati; I know that he could come with Pranay Roy, and take part in the NDTV initiated Banega Swachh India campaign. But then, his silence on many issues relating to the prevalent state of affairs in the country–particularly, at a time when a mix of totalitatrian politics and militant nationalism has caused a toxic environment of fear and violence in our society– is smewhat shocking. I know that he failed as a politician. Neither Rajiv Gandhi nor Amar Singh could give him the strength or strategy to survive in politics. Hence, I am not asking him to join politics once again. But then, an artist also known for the recitation of his father’s progressive poetry, powerful communication skills in English and Hindi ,and constant writings on his blog, could have contributed something more meaningful to the socio-cultural debate for awakening his fans. Yes, people loved him, and prayed for his recovery when the ‘Coolie’ was sent to the hospital after an accident in the studio. And even now, despite the presence of the three Khans, his innumerable fans love him. His words, I believe, matter. But then, why is he silent? Is it that the logic of success has enslaved him? Is it that it is no longer possible for the iconic Bachchan (so comfortable with his presence at Isha Ambani’s lavish and spectacular wedding) to evolve as a critic of the Establishment? Has the ‘angry’ man on the celluloid become an integral part of the system, and eventually a docile conformist?

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.