It is in this context that Guy Claxton’s research on wisdom, creativity and education acquires special relevance. ‘Wise action’, writes Claxton, ‘often has a light and contingent quality that ponderous rationality—the methodical weighing of pros and cons, and so on—often lacks.’ He explores further, and argues that ‘acting wisely is underpinned more by an intuitive moral clarity than by analytical precision.’ He wants us to realize that wise actions are different from cunning, smart, expedient, or merely intelligent actions. Because ‘wisdom takes account of the greater good and of one’s higher, deeper, or more lasting values.’ Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that wise actions need a degree of ‘disinterestedness’ on the part of the actor which enables him or her ‘to stand back from the fray and to see the predicament more objectively and in more of its all-around complexity’.

And above all, as Claxton reminds us, what characterizes the ability of the wise actor is ‘not only to get out of the way, but also empathize—to put him/herself in other people’s shoes and see the world as they see it, without becoming captured by the hurts or desires that, to those others, shine so blindingly bright’. The Age of Reason gives excessive importance to man’s intelligence—his cognitive skills, his analytical/logical faculty, and his ability to store hard information and become ‘knowledgeable’ to succeed as a professional. It is, therefore, not surprising that seldom do educationists talk about wisdom. Schools, colleges and universities valorize ‘intelligence’, ‘rationality’ and ‘success’. But is it possible to create a society without wisdom? Is it possible to evolve as an integrated human being without wisdom? Wisdom cannot be measured. Wisdom is not part of an academic discipline, be it physics or history. Wisdom does not assure what we value in our times—reckless economic growth, mass production of military weapons, gold medals in sports carnivals. Yet, there is a longing for wisdom (no matter how undefined the term is) without which nothing seems to have a deeper meaning.

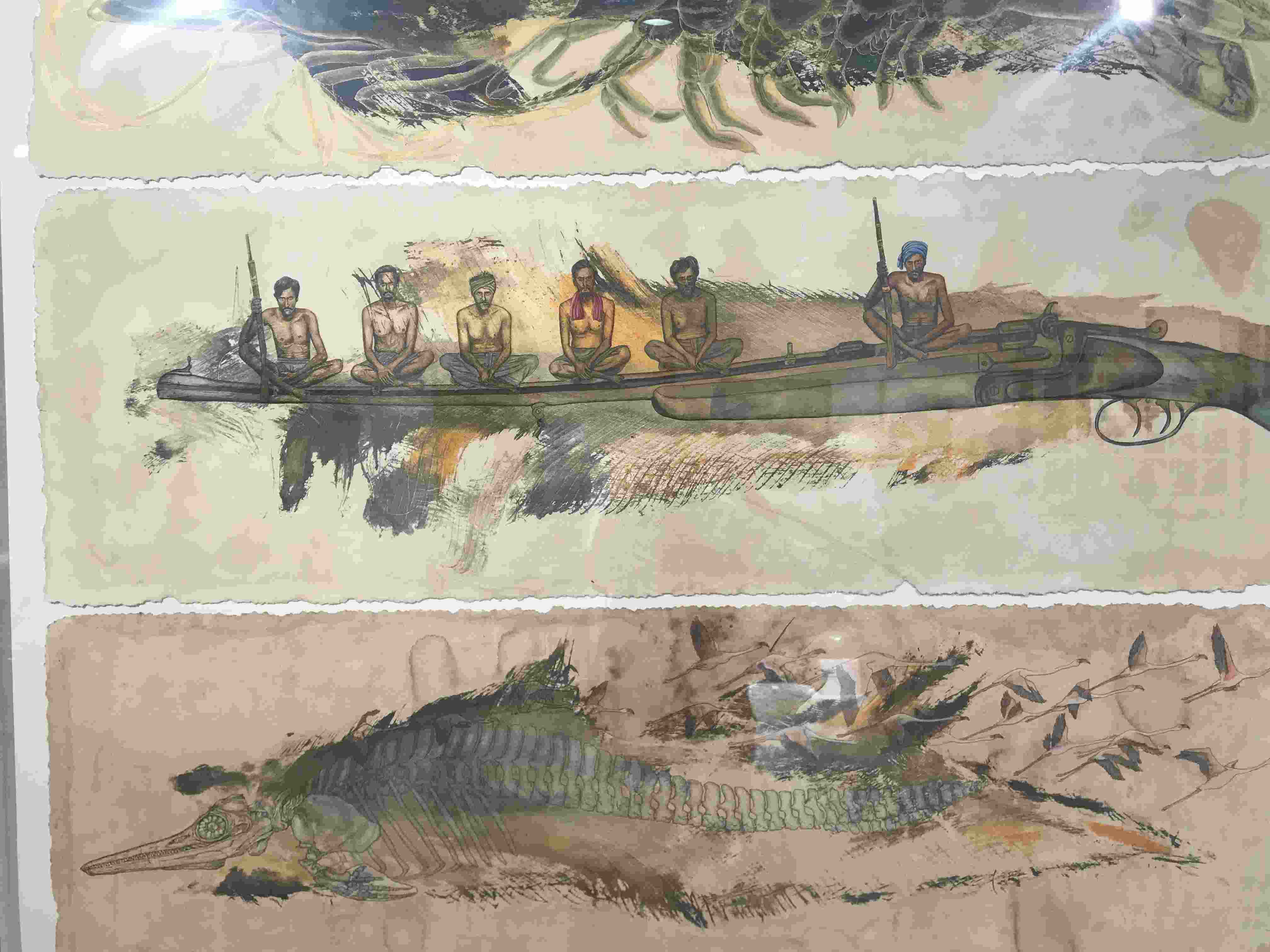

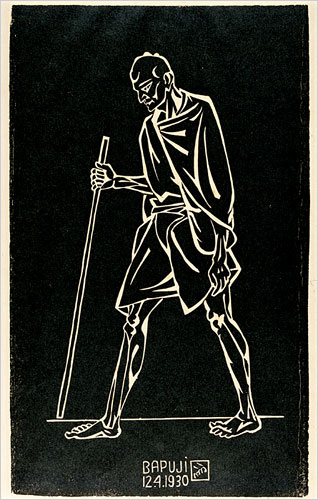

Wisdom implies creativity. But creativity need not necessarily be wise. Take a simple example. A management graduate from IIM-Bangalore may be extraordinarily creative in evolving business strategies for selling a particular brand of wine manufactured by a multinational company, however, there is no wisdom in his action because it is merely smart and expedient without a higher value. On the other hand, when Gandhi appealed to the Hindus to see the world also through the eyes of the Muslims, he was acting wisely because in that act there was a consideration for the greater good. To quote Claxton: “Wisdom has a necessarily moral quality. It functions for the greater good, rather than for the personal advantage or ego satisfaction of the wise actor. Creativity, on the other hand, is associated with the production of something novel and valued, or the innovative solution of a tricky problem, regardless of the moral dimension of the problem or the ego motivation of the actor. Designing new weapons of mass destruction or ingenious forms of torture could very well be called creative, within the normal meaning of the word, but no one would call them wise”.

Can wisdom be taught? It is pretty obvious—and Claxton too agrees—that it cannot be taught the way a teacher teaches geography or mathematics. Well, it is easy to construct a syllabus containing modules on the history of the notion of ‘wisdom’, the etymology of the word, philosophical problems in the definition, anthropological studies on the various views of wisdom in different cultures, famous candidates for the title of ‘wise persons’ , and so on. However, as Claxton states boldly, ‘none of this need have any impact on the cultivation of the ability to act wisely in any of the students in such a course.’ His research suggests something far deeper. Wisdom requires empathy—the ability to look at the world through the eyes of a range of other people. Yes, there are teachers who try to arouse this faculty in their students. Claxton gives an example:

In a social studies lesson in a comprehensive school in Cardiff, Wales, the class of 11-year olds thinks about the causes of the Iraq War. They wear spectacles cut out of blue cardboard. These are their empathy specs, which magically enable them to look at events through different people’s eyes. What do things look like to George Bush? To Tony Blair? To the sister of a soldier? To a widow in Fallujah? To the chief executive of BP? Of course, no magical advantage is conferred by wearing the specs; all that happens is that empathy is highlighted as a valuable ability, and by turning it into an entertaining activity, the ability is stretched and the disposition strengthened. That, at least, is the intention—and the results of this small pedagogical experiment suggest that it can be successful.

We live in a world that values instrumental rationality—one’s immediate profit, advantage and success. It is also a world in which we are becoming increasingly intolerant. With our heightened ego-centric individualism, we tend to devalue others; with our strong political/religious beliefs we tend to think that our position is sacrosanct, and everything else has to be eliminated. No wonder, it is becoming difficult for us to live with ambiguity, to realize that there can be multiple ways of addressing an issue. This causes impatience and ‘self-righteousness’. Wisdom is sacrificed because it demands another kind of disposition which, to borrow the language of John Keats, means: ‘being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’. As Claxton suggests, as teachers and educators we ought to cultivate this quality in our own lives, and encourage young learners to see the beauty of this process. And only then is it possible to create a world in which there is love and understanding, plurality and co-existence, and abundance of wise actions.

(SOURCE: Anna Craft, Howard Gardner, Guy Claxton (eds.) Creativity, Wisdom and Trusteeship: Exploring the Role of Education, Corwin Press, California,2008)