Feminism is Not a Cup of Instant Coffee

On the eve of International Women’s Day we seek to converse with our alert readers and raise a series of critical issues relating to the dynamics of feminism. Here is a small piece written by The New Leam editorial team.

The Substance of Feminism

There are certain things that are fairly known. Feminism is a movement, a consciousness—a quest for a just world characterized by the ethos of a reciprocal, symmetrical and dialogic relationship between the sexes. Gender, unlike biological sexuality, is socially constituted. Feminism is not anti-men; instead, it reminds men of the violence implicit in patriarchy which as an institution of power and possession privileges and brutalizes them, subjugates and silences women, and causes a hierarchical duality—‘masculine bravery’ vs. ‘feminine passivity’; male-dominated public sphere of work and economic production vs. women-centric domestic realm of care and reproduction. And it is also known that with the passage of time and the development of feminist movements, there are many schools of thought with diverse, conflicting and overlapping brands of feminism. For instance, Simone de Beauvoir saw the objectification and subjugation of the ‘second sex’—the way in patriarchy man as a privileged subject sees woman as the ‘other’. Isn’t it the reason that, as Beauvoir argued, in the Freudian psychoanalysis male sexuality is the vantage point through which female sexuality is perceived as the ‘other’—women suffering from ‘penis envy’, growing up with weak ‘superego’ and with ‘feminine’ traits like envy and jealousy? With deep sensitivity to ‘existentialism’, Beauvoir debunked this sort of ‘essentialist’ argument, and pleaded for a culture in which every moment men and women can redefine their life-projects without being burdened with the notions of some innate/ fixed ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ essence.

If Simone de Beauvoir gave a great momentum to feminism, today we can see yet another form of feminism—say, ecofeminism—that reminds us of love, ethic of care and affinity with nature as distinctive features of femininity which, as it is argued, are needed for rescuing the world from the hyper-masculine Baconian science and technological domination of nature, and creating an ecologically sustainable and gender sensitive world. From ‘liberal feminism’ concerned with ‘rights’ to ‘postmodern feminism’ questioning the logo-centric male thinking and pleading for differences —the exploration continues.

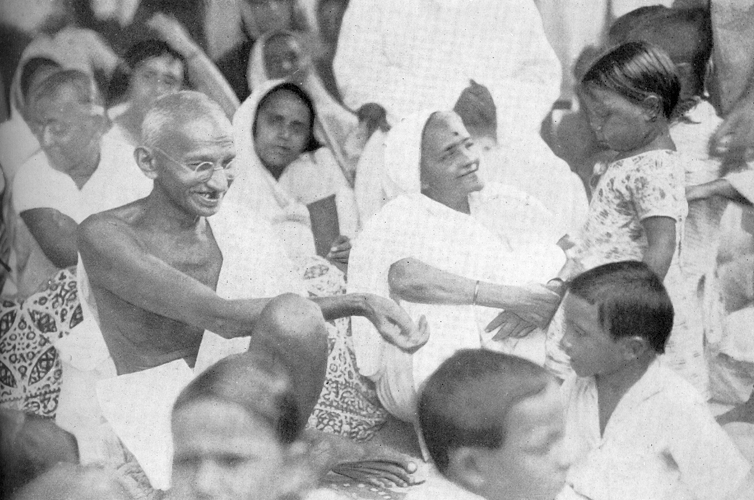

Likewise, while the likes of Sarojini Naidu inspired by the spirit of the Gandhian movement visualized a new woman—spirited, political and courageous; yet, deeply moral and rooted in the civilizational ethos; the new feminist groups in the 1970s—inspired by Marxism and other modes of politics of resistance— launched a movement against the harsh reality of dowry, rape, sexual violence and everyday oppression in the family. Furthermore, it is argued time and again that women do not constitute a homogenized category, and there is no universal ‘sisterhood’. Be it caste and class, ethnicity and religion—women, like men, differ in terms of their social/political/psychic experiences. The agony of the wife of a construction worker with her malnourished baby in the anonymous streets of Delhi is qualitatively different from that of a female chairperson in a university department dealing with her problematic male colleagues; male power in a posh Vasant Vihar colony or in the hyper-real Hauz Khas village might manifest itself in a different way from the way the alcoholic daily wager in the ghettoized slum of Delhi beats his wife and daughter. However, despite these diverse approaches and experiences, there is a thread of connectedness; and this means that the hierarchy that the institution of patriarchy (if there is brahminical patriarchy, there is also Dalit patriarchy) creates is not natural, biology is not destiny, and it is possible as well as desirable to create a new world based on love and trust (a hard working woman in the remote hills of Uttarakhand needs it; and it is also needed by a middle class/English-speaking housewife in the urban locality who seldom finds the ecstasy of togetherness because of her ‘successful’ husband’s corporate responsibility and business tour) rather than asymmetrical power relations erecting walls and causing spiritual distance, and it is in this sense that feminism as profound spiritual- humanism is a liberating experience.

The Danger of Trivialized Feminism

However, in the absence of a critical pedagogy feminism can be trivialized, distorted and reduced into its lowest denominator. We can see its two central features. First, it loses its depth and assumes that the task is only to internalize the rationale of the oppressor, and become like them. And hence if patriarchy valorizes violence, domination, instrumental rationality and aggression, a ‘liberated’ woman too ought to be like the ‘powerful’ man. The exercise of brute power as such is not bad only if women too are allowed to practice it. This does not alter the logic of the game; instead, it accepts this logic. No wonder, quite often, ‘courageous’/’liberated’ women would be seen as the ones excelling as army officers, pilots in the air force, or as ‘iron ladies’ in the ruthlessly corrupt/ violent political domain. This does by no means suggest that women are incapable of playing these roles. This means that this ‘courage’ itself is problematic; this brutalizes men as well as women. And see its consequences. The logic of patriarchal violence remains unchallenged; war or brute nationalism is not questioned; and the aggression of politics is seldom interrogated. From the Queen of Jhansi to a woman journalist covering the Kargil War—it is assumed that a ‘liberated’ woman too knows the game, its hardness, its strategy. This notion of ‘success’ and ‘courage’ internalized by the ‘women of substance’ reproduces the same hierarchy, and this time among women themselves: the likes of Indira Gandhi or Mayawati are more heroic and more courageous than , say, a tremendously hard working and dedicated sister in a public hospital, or a woman scientist working silently in her lab, or a mother of three children publishing poetries and short stories in literary magazines!

Second, it overemphasizes the superficial. The discourse of freedom remains confined to a set of external behavior patterns. As a woman, can I attend the late night party, drink and smoke, wear whatever I wish to wear, establish the control over my body and sexuality? Nobody is denying the importance of these small spaces of freedom. However, if these experiences are not organically related to the deeper idea of emancipation, things are likely to remain at a very superficial level. Is the late night party in a pub I wish to attend really about my dignity and autonomy as a woman, or is it about objectification, ‘permissive sexuality’ reducing both men and women as fleshy objects engaged in fleeting encounters? Do I really have control over my body and sexuality when the market-driven culture of simulation and consumption has already dictated the choices for me—the particular shade of Lakme lipstick I use, the fashion designer whose interview Femina or Stardust has published in its glossy pages, the film actress whose mode of dressing has already become the norm? In fact, as consumerism makes patriarchy colourful and sleek, freedom loses its philosophic and spiritual substance, it becomes the desire to consume, and feminism in its trivialized form becomes a glossy product, a cup of instant coffee. Not Simone de Beauvoir or Veena Mazumdar, but Deepika Padukone’s video becomes the central text; dancing in tune with Honey Singh’s songs (isn’t it the symptom of the growing pornographic mentality that distorts the beauty of the Eros as life-affirming/positive energy) in the lavish wedding party becomes the ritual of liberation. This is the ultimate irony.

Feminism as Men’s Conscience

Before it is misunderstood, it is important to state that we are not seeing women as primary responsible for the restoration of the moral landscape. In fact, it is the shared responsibility of the collective citizenship—men and women—to fight the growing pathology of mass culture, its sexual imageries, the way it equates freedom with a sense of ‘having’ or gross pleasure. It is important to remind ourselves of the profound nature of feminism, and how as a liberating practice it is also about men. In fact, feminism in its finest moment is the voice of conscience for men. It makes them reflexive, enables them to look at themselves, and acknowledge how patriarchy tends to dehumanize them and kills their softer sensibilities for carrying the heavy burden of ‘masculine ego’. And this lesson can lead to a delicate task in redefining ‘masculinities’. See three broad notions of being ‘man’ (and of course, these are modulated and shaped by historical locations, and caste/class affiliations) in a patriarchal setting. First, this means that as a ‘man’ I am powerful, I am hard, competitive, I know how the reality outside functions, and hence it is my responsibility to ‘teach’, ‘civilize’ and ‘control’ women. Second, it also implies that because of my power and privileged position, I ‘protect’ them, retain their ‘honour’. I am paternalistic. And at moments I pamper them; my woman is my ornament, my status! And third, I make a sexual division of labour. As a ‘man’ I am the economic agent in the ‘productive’ sphere of ‘work; and even when I allow them to enter the public sphere they ought to balance the two—their ‘mothering’ qualities of care and their professional roles as teachers, doctors, fashion designers. In all these three types, as we see, there is no possibility of a truly symmetrical relationship; instead, it is the practice of power that manifests itself in the experiences women pass through—sexual objectification and physical violence; or the compulsive urge to live like ‘dolls’ (pampered dolls for men’s play) as Ibsen’s classic A Doll’s House depicted; or ‘working women’ endowed with the heavy responsibility(men can safely omit this task) to reconcile the twin spheres home and the world!

Feminism is asking men to redefine their ‘masculinities’ and restore what they seem to have lost—the spirit of dialogue, the ethic of care, the non-hierarchical consciousness, and the ability to love, surrender and cry. And yes, feminism in its critical aspect is also asking women to look at themselves, fight what they have internalized as victims because of the all-pervading patriarchal hegemony ( we are like this; our ‘beauty’ and ‘softness’ matters; it is good to be pampered and protected by men; and it is not nice for our men to behave like ‘women’, become ‘effeminate’, spend time with the kids and take unnecessary interest in the kitchen), and prepare themselves for a humane/reciprocal/spiritual relationship with men and the world.

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.