LITERATURE

In a new collection of short stories written by Indian male authors, an attempt has been made to step into the women’s’ world with radical insight and keeping into mind the contemporary context. But can male writers really step into the world of women?

Sameera Roshan is a Literary Critic based in Chennai.

Can men tell the stories of women with as much empathy and realism or is it impossible for a man to let go of the male self and step into female subjectivities? This has been a question which is often asked but seldom answered. While it is true that men and women inhabit the world of their own distinctive subjectivities, what cannot be denied is the fact that literary creations have allowed them both to step into each other’s subjective realities and ‘feel’ what it means to be the opposite gender.

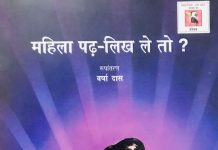

To find a possible answer to the difficult yet extremely intricate question about men being able or unable to step into women’s subjective realities, a collection of Urdu stories can become useful. In a beautifully crafted and carefully designed book ‘Preeto and Other Stories’, the male authors step out of their comfort zone and assume women’s’ voices. But what is extremely central to the book, is the fact that all the male authors have left behind their male subjectivities and adopted a radically non-conservative perspective. Preeto and Other Stories: The Male Gaze in Urdu is a book that has been edited and introduced by famous historian Rakshanda Jalil. The book gives the readers a refreshingly fresh perspective about aspects of contemporary women’s’ subjectivities and offers a glimpse of their worlds.

The collection is composed of short stories that explores important aspects of femininity and captures contemporary ethos. The short-stories have been all composed by contemporary men writers, but what is immensely thought provoking is the fact that these men have tried to adopt the woman’s voice and articulate her ways of seeing and relating to the world. The approach that these men take are radically refreshing and non-conservative, they talk about the dilemmas that women go through, the dreams that they have, the way they deal with relationships and the way in which they find themselves.

‘Real’ and not ‘Ideal’ Women Must be cherished

The selection of short stories has deliberately chosen stories that discard the tales of women that promote a vision of a certain ‘ideal’ womanhood or put unrealistic demands on women. The effort has been towards making the women characters as real as possible, as flawed and relatable and depicts them in identifiable femininities- that sync with the lived experiences of many women in our times. What makes this collection of immense importance is the fact that it frees women from restricted moulds, frees them from the compulsion of having to please a patriarchal society and grants them a distinctive voice. In her beautifully composed introduction to the book, Jalil has talked about the literary creations of Manto, who had the flair for writing about women as realistically as possible. Manto never portrayed his women as if they were creatures from another planet but made them as relatable as possible.

These authors contributed immensely to the way, women were understood and gave expression to the physical and emotional desires of women. The desires of women, their physical needs or their emotional turmoil were naturalised by Manto and taken out from the unholy circle of taboo and social disgust. The collection of short stories reminds us of the fact that there have been many Urdu writers who have chosen to see beyond the conventional femininity and given women a more realistic and contemporary characterisation in their stories. Women are indeed undergoing a transformation in terms of their breaking away from the traditionally held expectations and coming face to face with their own individualistic identities. The book speaks of the birth of a new woman, in search of her own individual self. The stories are relatable and allow the readers to explore the world of women who will be struggling to find themselves within a patriarchal system. Some of the remarkably beautiful stories in the collection include Baig Haya’s story “The Heavy Stone” which is about the pain and dilemmas that a woman undergoes when she decides to abort her baby due to financial constraints. In another story called “ Man” written by Gulzar, the question is about why women have to always be answerable to the male members in her family and how even her own sexuality is seen as guarded by a man. The social context in which women negotiate power and find themselves is imaginatively depicted through these stories.

The book does not make a claim that the social orientation towards women has changed or that literature is more in tune with the world of women today, but all is does is that it makes us aware of how contemporary Urdu literature is coming to terms with contemporary notions of femininity and the liberation of the woman’s thinking. The book is an interesting read and a celebration of the ‘real’ and ‘flawed’ woman rather than a morally-burdened and ‘ideal’ woman.