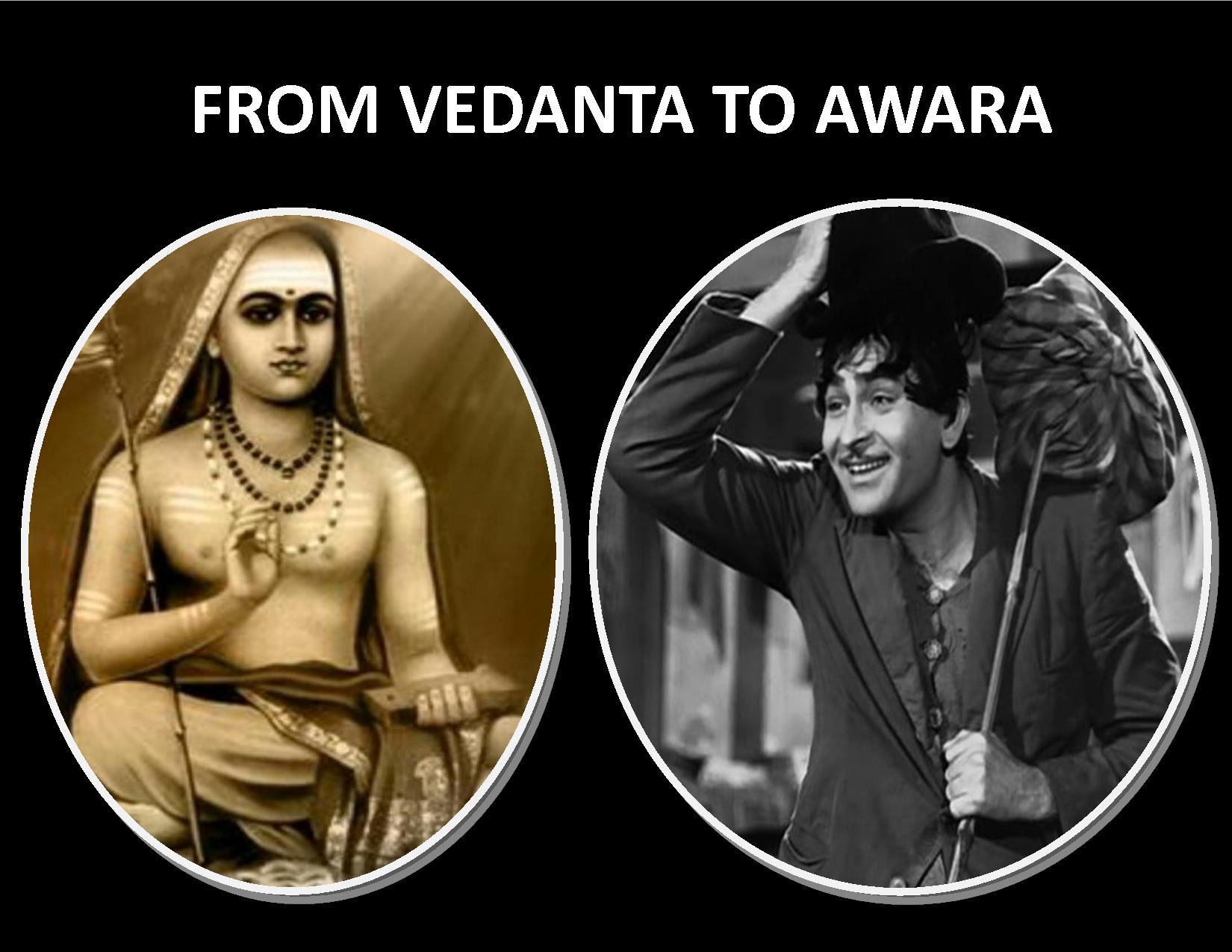

From Vedanta to Awara

‘India’s history is a curiously unpeopled place’. Sunil Khilnani—the author of The Idea of India— opens his new book Incarnations with this revealing statement. True, we have ‘dynasties, religions and castes’, but ,as Khilnani reminds us, ‘beyond a few iconic names , most of the important historical figures recede into a haze’. The book, to use his own words, ‘is an experiment in dispelling some of the fog by telling India’s story through fifty remarkable lives.’ True, not all important figures can be included in a single book. If there is Indira Gandhi, why is Jawaharlal Nehru absent? Or, for that matter, if there is Subbalakshmi, why is Pandit Ravishankar absent? Khilnani gives a beautiful answer: ‘The impossibility of being representative , or allinclusive, has also given me freedom. I’ve chosen to leave out some familiar names, to allow space to bring in a few others who should be more widely known.’ A careful reader, we believe, would agree with the author that Incarnations is an ‘open invitation to a different kind of conversation about India’s past, and its future.’ After all, as he says, ‘a civilization able to produce a Mahavira, a Mirabai, a Malik Ambar, a Periyar, a Muhammad Iqbal and a Mohandas Gandhi is a place open to radical experiments with self-definition.’ In this column The New Leam has chosen to present before its readers Khilnani’s simple (yet immensely revealing) narration of the tales of Adi Shankaracharya and Raj Kapoor. In India how can we separate ourselves from the domains of religion and popular cinema?

(I)

Adi Shankara

Shankara, or Shankaracharya as he was also known, supposedly began travelling across India at a young age. As with so many of these ancient figures, there’s uncertainty and dispute about his early life. It’s generally reckoned that he was born in the eighth century, in the Malabar region of southern India, now in the state of Kreala. Some religious biographies , written in verse several hundred years after Shankara’s death, claim that the deity Shiva appeared to Shankara’s parents in a dream and gave them the choice of producing a son who was ‘all-knowing and virtuous but short-lived’, or one who would live long but ‘without any special virtue or greatness’. They opted for the former, and named their precocious child Shankara, another name for Shiva. As promised, the boy turned out to be a prodigy, but was just thirty-two when he died.

It was said that Shankara only had to hear something once to remember it, and that he had mastered the four Vedas, the oldest Hindu scriptures, by the age of eight. Around the same time, or possibly even earlier, Shankara declared his desire to become a sannyasi, an ascetic, wandering monk. This announcement scandalized his by then widowed mother. In the traditional lifecycle of a Hindu male, sannyas—renounciation of the world—is the fourth and the final stage. A boy first has to grow to be a student and then an adult householder, and then later withdraw into hermetic retirement. Only after that can he take the final step and become a religious wanderer.

But Shankara prevailed and , by the age of sixteen—with half his life already spent as an ascetic—he was producing sophisticated scriptural commentaries and articulating a radical new version of what eventually became known as Hinduism. He remained devoted to his mother, though. After she died, Shankara returned home intending to perform death rites, but his community refused to let him. Only a householder could do the rites, they said—not a sannyasi. It was a painful snub, and perhaps the pivotal incident that turned Shankara against high Brahminical rituals and towards what he considered the undervalued inner wisdom of post-Vedic texts. …

As a result of this tenet, Vedic Hinduism had to be newly formulated, and turned away from popular forms of worship, which, according to Shankara, misunderstood the individual spirit’s path to liberation. Obsession with rituals had to be replaced by asceticism, celibacy, the giving up of family life, and an intellectual rigour that could help others grasp the truth that the seeking person divined. Instead of mantras, Shankara prescribed meditative reflection, through which each individual could pierce the veil of maya and come to recognize the universal spirit. Once we grasp that oneness with the eternal, Shankara said, we attain moksha, or release from the cycle of life and death. …In his efforts to capture the ineffable oneness of the universe, he produced a beautiful, if at times confounding, literature:

I am neither earth nor water nor fire nor air nor sense-organ nor the aggregate of all these; for all these are transient, variable by nature…I am neither above nor below, neither inside nor outside, neither middle nor across, neither the east nor west; for I am indivisible, one by nature, and all- pervading like space. …

In his lifetime Shankara’s teachings gained him many devoted followers, but it’s the afterlife of his teachings that makes his doctrine far more popular today than it ever was in the eighth century. His prouned-down version of Hinduism caught the interest of the broad-minded Mughal emperor Akbar in the sixteenth century, and later found a ready ear among India’s nineteenth century colonial masters. …At the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Hindu revivalists and Indian nationalists embraced Shankara’s philosophy as a muscular indigenous religion. Thinkers such as Swami Vivekananda invoked Shankara’s ideas and argued for the creation of schools to promote Advaita Vedanta and foster national pride.

(II)

Raj Kapoor

In Awara (1951), Kapoor’s third film and one of the most successful of all time, Nargis plays not just the love object but a practicing lawyer. Kapoor plays a thief and a vagabond—an ‘awara’—who adores her. As many of Kapoor’s films , the faults of the poor spring from the wrongs of the rich. In one exchange, Kapoor’s character describes the miracle of modern society: ‘Capitalists, black marketers, profiteers and money lenders: Who are they? All thieves like me.’

By now Kapoor had assembled a trusted team of collaborators, among them the Marxist novelist, political columnist and neorealist scriptwriter Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, who, like Kapoor’s father, had belonged to the IPTA group. Abbas had modeled himself on the muckraking American novelist Upton Sinclair. Shailendra, a poet and author of many of Kapoor’s most famous songs, was only slightly less left-wing. Awara spoke to the mass unemployment following Independence, as well as corruption in the criminal justice system. Kapoor’s next film, the enduringly popular Shree 420 (1955) was an even sharper critique of upper-class corruption, and conveyed a deep appreciation of the difficulty of behaving ethically in a world intricately rigged against the poor—even for honest souls with college degrees , like its protagonist. The title comes from the section 420 of the Indian Penal Code, on fraudsters. The rich in the film seem to be born dishonest; the dishonesty of the poor is India-made. It was a theme that packed in the film-goers. …

The acuity of Kapoor’s class analysis reached its apex with his production of the relatively unsung Jagte Raho (1956), in which a rumor of a thief loose in a middle-class community prompts the people to organize their impoverished neighbors into armed goon squads; poor men eager to beat off the ‘thief’, who is really a destitute peasant, recently migrated, in search only of a drink of water. This absurdist comedy of middle-class snobbery and petty perfidy demonstrates a canny handle on how the lower classes are used as tools to undermine those with whom they might find common cause. But as is typical in Kapoor’s films, the conflict is ultimately mollified by kindness. As hard as the world gets, there’s usually a loving Nargis on the way, ready to slake thirst with a small gift of water.

It was, as Nasreen Kabir puts it, a Marxist analysis of problems that proposed no Marxist solution. A ‘professional emotionalist’, Kapoor seemed to be suggesting that you could love your way towards equality and dignity, or at least love your way around the structural problems of your society. In Shree 420, raj and Nargis walk in the middle of an empty road during a monsoon shower, singing ‘Pyar Hua Ikrar Hua’, the most famous love song in the Kapoor repertorie. The couple is in a bubble of romance, apart from the world, and they know the road ahead is hard, despite a future in central government ‘people’s housing’. But as Nargis makes clear with a gesture and a flash of her eyes, babies will figure in in the couple’s non-centralized five year plan. If the promise of Indian Independence was not to be realized imminently, Kapoor seems to hint, perhaps the second generation of young, spirited Indians would have better luck. …

Awara opened in the USSR in 1954., the year after Stalin’s death. Under the so-called Khruschev thaw , there was suddenly a new freedom in media and the arts. In that year alone, a stunning 64 million people—mainly young people—are estimated to have bought tickets to Awara. ‘Kapoor-mania’, as it was called in the USSR , became even more frantic with Shree 420 the next year. Soviets didn’t require Marxist solutions in their films; there was plenty of that on the state-run radio. They celebrated the songs, which became ubiquitous on the airwaves, and bought postcards with Raj’s image (cult collectors’ items to this day). They made the young hero who pursued his desires against social traditions their own.

Source: Sunil Khilnani, Incarnations: India in 50 Lives, Allen Lane, 2016

This article is published in The New Leam, NOVEMBER-DECEMBER Issue( Vol.2 No.16-17) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

If You Liked the article? We’re a non-profit. Support This Endeavour – http://thenewleam.com/?page_id=964