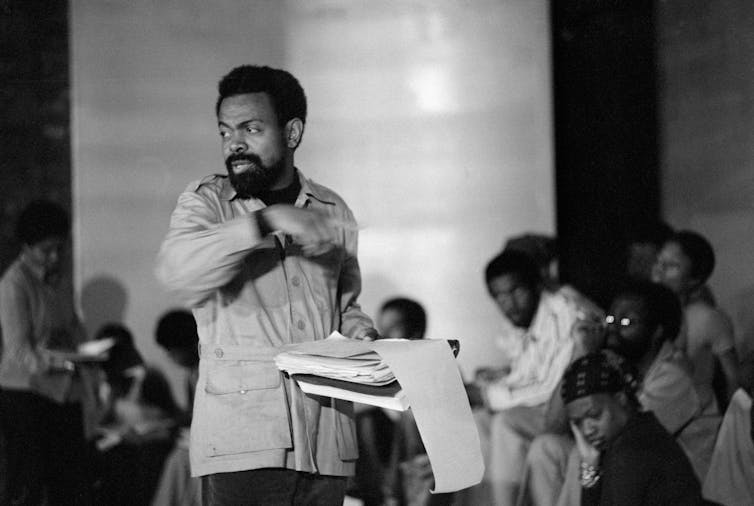

Keorapetse Kgositsile, the South African-born poet who passed away in 2018, lived in exile in the US from 1962 to 1975 and was at the centre of the country’s 1960s and ’70s Black Arts Movement. Informed by his South African and Tswana background, the poet makes a case for multiple inflections of voices, geographies, and histories in the making of transnational black modernity.

Analysing his work offers ways in which African poetry can disrupt dominant thinking on Black Atlantic studies, particularly Paul Gilroy’s

1993 text The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. The Atlantic world referred to by Gilroy tells the histories of Europe, Africa and the Americas, two hemispheres joined by the Atlantic ocean and exchanging influence. Kgositsile’s poetry can be read as challenging the direction of influence from north to south.

Uhuru Phalafala considers the rich oral traditions passed on from Kgositsile’s grandmother and mother as a key system of knowledge that informed and shaped his black radical imagination. Aretha Phiri interviewed her.

Aretha Phiri: Your colloquium paper situates the celebrated poet-in-exile at the centre of and as uniquely influential to the Black Arts Movement?

Uhuru Phalafala: It was a time when African Americans were seeking to define their identities, with Africa as key metaphor. Kgositsile happened to not only come from that continent, but also used his mother tongue, Setswana, spiritual practices, and music from southern Africa in his work. By interweaving Tswana vernacular with the black diaspora parlance, he affirmed African America’s legitimate affiliation to the continent, as seen in the example of his influence on “the grandfather of rap music”, The Last Poets.

He also came from a mass liberation movement that was experienced in politics of armed confrontation, generated solidarities with other liberation organisations, and adept in decolonial politics. His work became a resource for his contemporaries. Today, when we look at, for example, Kendrick Lamar’s influential album, To Pimp A Butterfly, and the number of references to South Africa in it, we must understand it as grounding itself in the foundation that people such as Kgositsile laid in the sixties and seventies. South Africa will always have an enduring place in the African American imagination.

This is diaspora consciousness. He also admired Nina Simone’s sound, which he called “future memory” to signal that it is not new or emergent, but reminiscent of the protest tradition of South Africa.

Aretha Phiri: In focusing on the oral traditions inherited from his female lineage, you make a case for the specific use in his poetry of a “matriarchal archive”?

Uhuru Phalafala: The colonised come from different conceptions of time (temporalities). Colonial temporality is not only racialised but also gendered. The arrogant coloniser inaugurated the beginning of history in his assumption that we did not have a history before he arrived. “History” began with the arrival of the coloniser, and marched forward in a linear fashion. With time, black men accessed modernity’s time – through missionary education and working in the mines – at a different period than women.

We now know that when anti-colonial wars were fought they were primarily and solely about the emergence of the black race from subjugation. When women and queer people attempted to bring the particularities of their oppression to the agenda they were told to wait. When independence was achieved those doubly and triply marginalised did not attain their independence at the same time with their countries because they continued to fight against black patriarchy.

If we backtrack we can then make certain observations. A type of double location of time was constructed when the colonisers’ history was instituted: theirs and ours. Because of lack of contact with missionary education and industrialisation, loosely speaking – of course there were women who accessed modernity – women occupied a different temporality. One of continuity from precolonial to colonial time, with its attendant way of life, philosophies, worldview, oratory practices, etcetera.

Aretha Phiri: In describing this archive, how do you guard against potential accusations of advancing a gendered essentialist claim?

Uhuru Phalafala I do not wish to rehash gendered essentialist claims. This is just historical process. My grandmother never set foot in a classroom but has a world of knowledge, so to say. Men who were later ferried to missionary schools, or those who went to work in the mines en masse, existed in a double location of time. The flow from precolonial to colonial time was interrupted by modernity’s time, fashioning a coexistence of the two.

These men came face to face with the colonial alienation and “first exile” from their home cultures which were denigrated by colonial assumptions of superior culture. This is how temporality is also gendered. The women who suffered the blows of this history, mostly in the rural countryside, continued to live life on their own terms, without their men. They continued to practise their indigenous ways of knowing – which are not an event but an ongoing process.

These knowledges evolved with time and did not freeze in some dark past. They progress, transform, and evolve as humans do. Today when we call for decolonisation we are actually wanting to retrieve this knowledge that was silenced and erased by the multiheaded hydra of colonialism. Where can we find it if not from those who had little contact with this hydra? In my view black women, in the context of southern Africa, are that “matriarchive”.

The book Black Radical Traditions From The South: Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement by Uhuru Phalafala will be published shortly.

This article is part of a series called Decolonising the Black Atlantic in which black and queer women literary academics rethink and disrupt traditional Black Atlantic studies. The series is based on papers delivered at the Revising the Black Atlantic: African Diaspora Perspectives colloquium at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study.![]()

Aretha Phiri, Senior lecturer, Department of Literary Studies in English, Rhodes University and Uhuru Portia Phalafala, Lecturer, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.