Books are windows to the world and good books are essential companions to the development of sound intellect and sensitivity. Here is an engaging review of a recent and much talked about book.

Kanak Yadav is a doctoral candidate at Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Her areas of research interest are – Dalit Autobiographical Narratives, Indian Writing in English, Translation Studies and Nonfictional accounts of Indian Urban Spaces.

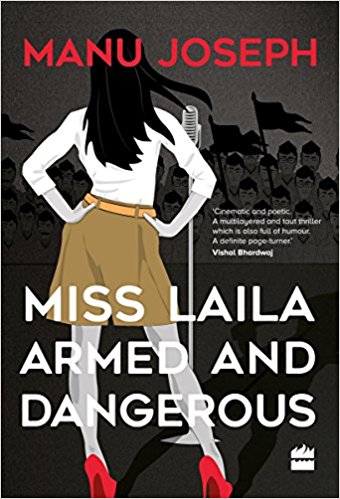

As a society which suffers from collective amnesia, a simple Google Search or, for more politically-aware readers, a trip down the memory lane of contemporary history, would enable the discovery of the topicality of Manu Joseph’s new novel, Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous. By blurring the lines between fiction and nonfiction, Joseph’s new book is an ambitious, political satire which lampoons State politics (and its benefactors), digital cultures and activism, irrespective of their ideological differences. What would have become another polemical piece, had the satire been one-directional, Joseph’s fascination for the ridiculous does not spare anyone, which is refreshing in times where political positions mark the order of the day. However, it equally invites questions on how viable are the possible alternatives envisioned in the novel.

Having said that, Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous is a political text: It is political by refusing to fashion itself around any given ideology. Instead, by caricaturing the authoritarian beliefs and the moral high-handedness of both the Indian Right and the Left respectively, which has become a signature feature of contemporary politics, it provides a scathing critique of social-media activism. By interrogating buried pasts, socio-religious stereotypes and providing access to the psychology of the characters and the lonely worlds they inhabit through a third-person realist narrative, the writer critiques the “new India” of today. As the story unfolds, the reader is witness to the change in the political regime for it is the day of the election results, and Damodar Bhai is about to become the new prime minister. Against this backdrop, we come across a comedian-cum-movie-maker, a “trending” prankster, Akhila Iyer, (in) famous for making videos titled How Feminist Men Have Sex, who is in conversation with a dying man caught under the debris of a fallen building. As the injured man describes to her the movement of a Muslim couple who pose a threat to national security, in simultaneous events, Professor Vaid, a Sangh ideologue, closely follows his descriptions through telephonic conversations with a shadowy-figure named AK. In another scene, Mukundan, an agent from the Intelligence Bureau, follows the suspect, a middle-aged man, Jamal, and the teenage woman accompanying him, to strategically execute the plan of his capture. Even as the reader attempts to make sense of the puzzle, which juxtaposes diverse scenes from the rescue operation to the chase, this thriller offsets the reader by the time it prepares for the conclusion.

Though surely a page-turner, written in an accessible language, which is sharp in its satire but measured in its depiction of the ordinariness of life, it also shares the desire for the perverse, a recurrent theme visible in both his earlier novels – Serious Men and The Illicit Happiness of Other People. Written in an evocative language, it nudges the reader to question and rethink:

“Do people really believe that sadists live alone in a dark room? He can take you where sadists are more likely to be found – in the very places where the miserable come for relief.”

Neither sentimental nor conjectural, Joseph’s characters are flawed, which is what makes them believable. By telling tales of individuals trapped in a lone battle – one thinks of Ayyan Mani, the trickster-figure, from Serious Men, and his attempt to avenge caste Hindus through deceit – the narrative does not even consider the possibility of a collective rebellion rather presents it as an utter failure. Is this the cynical take of a satirist who does not believe in narrative redemption or the prankster has much more surprises to offer in disguise than otherwise? Whatever response the above question invites, one thing is clear that Joseph’s “political incorrectness” might seem populist but it allows an entry point for various ethical issues that are conveniently brushed aside in the public domain. What seems like a comment on a character’s style of narration, equally becomes exemplary for Joseph’s fiction, if not all his writing: “Her films are not all monologues. Most of her films, in fact, are pranks.” Joseph’s novels, too, appear as pranks directed to offend a society that has gone disarray. In this case, however, it’s a prank that shocks the reader into identifying his/her own complacence.

This article is published in The New Leam, OCTOBER 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No. 29) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com