Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man [woman] whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him.

– M.K.Gandhi

A 12-year-old girl, named Jamlo Makdam died after walking nearly 150 kms from Telangana to her native village in the Bijapur district of Chhattisgarh. Only a couple of days earlier, Rahul, an 11 year-old lost his life to hunger and starvation in Bihar’s Arrah. After the sudden announcement of a nationwide lockdown as a measure to contain and control the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, we saw how the media was flooded with images and visuals of India’s migrant class undertaking tremendously long journeys back home from the urban centres.

The lockdown implied a complete closure on all forms of economic activity, leaving India’s migrant class unemployed and completely helpless primarily in urban centres where the cost of living is much above their levels of affordability.

With no source of income and scarce savings exhausted just within a couple of days, many among these migrant workers decided to undertake the arduous journey back home on foot.

While the coronavirus pandemic and the vulnerability to catching the infection was surely a concern, a bigger challenge was imposed by hunger and thirst, exhaustion and fatigue that accompanied them on the way. Children, women, old and young walked for kilometres without proper food or a place to rest, only to reach back to the comfort of the family and the neighbourhood amidst the looming crisis.

But back at home too, financial inabilities and exhausted savings did little to comfort these migrant workers. While many migrant workers lost their lives to starvation and fatigue while on the way, several others were put in quarantine camps on state borders without adequate arrangements and some who managed to reach back home had no food or rations to sustain themselves.

While civil society organisations and local administrations worked endlessly to create food and night shelters, these arrangements were clearly insufficient to tackle the problems of the migrant workers.

Migrant workers: making the Country, but not part of its political imagination

Image:Dailytelegraph.com.au

The migrant class runs the informal sector, its everywhere from construction sites and factories to local shops and eateries, sanitation departments to security guards- despite playing such an integral part in cities and urban spaces, they are nowhere in its list of priorities as far as public policy or constructive measures are concerned.

This point becomes sufficiently clear if we look at how in a recent move, the governments of UP and MP arranged for transportation networks to bring back students from Kota or how an MLA from BJP was sanctioned a travel permit to privately pick up his daughter from Kota on a private vehicle despite the lockdown.

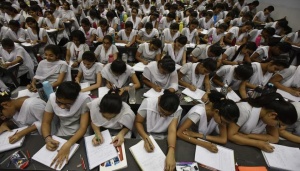

Thousands of students study at Kota to fulfil their dreams of cracking the IITs and the medical entrance examinations, they largely come from middle class homes and represent the aspirational youth.

They belong to a section of the population that constitutes the chunk of the middle class vote bank and is projected as the country’s future.

They are important for the state and not the likes of Makdam Jamlo and Rahul who although young and hardworking, will never be seen as the desired youth for whom the state ought to work.

Kota’s students are important as many of them will become doctors, engineers or civil servants or fly abroad for employment and send dollars back to the country but not Makdam Jamlo and Rahul or the lakhs of children like them, who will struggle and toil, work tremendously hard and still be unable to eat two meals a day, pursue an education or even seek medical care when ill. They are not and never were part of the national imagery.

It’s almost seventy years since independence, but India’s poor, composed of the landless farmers, labourers and sanitation workers have not been included in the nation-state’s priorities. Economic disparity, marginalisation and state neglect have continued to push them to the perils of decadence.

All political parties claim to work for the poor, but ironically it is the poor who loses out the most and continues to grow poorer. The divide between the rich and the poor has been magnified and it wouldn’t be wrong to say that the struggles of Gandhi and Ambedkar for the empowerment of the marginalised and impoverished look more relevant now than ever before and continue to remind us of the injustice embedded in the game of mainstream vote bank politics.

Chhattisgarh’s Makdam Jamlo and Bihar’s Rahul represent India’s poor and its struggle for survival in a hyper-capitalistic, Neo-liberal India that prioritises middle class aspirations and works for smarter cities but not equipped and self-reliant villages and towns, that celebrates the success of Indians attaining green cards and composing diasporas in the West but is least concerned about seeing quality teachers to remote rural schools or making quality healthcare accessible to all.

We are indeed living in an India that is urban and city-centric, elitist and metropolitan in terms of its policies and chooses to negate, disregard and allow the decadence of its vital lifeline: those who construct its building and guard its walls, toil in factories and farms and serve in its godowns, put their lives at risk and step into its sewer tanks and lay its railway tracks. The lockdown has unveiled the face of India’s mainstream politics and laid bare its priorities. The point is, will we have the courage to acknowledge it?

Vikash Sharma is founding editor of The New Leam. E-mail: vikashsharma946@gmail.com