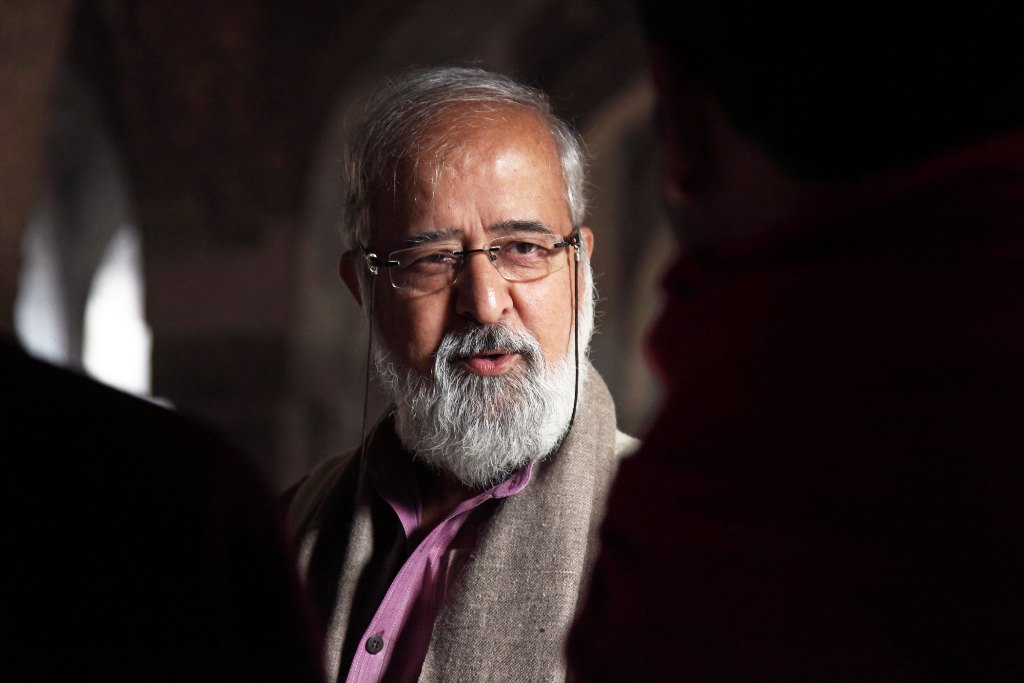

Sohail Hashmi is a well-known history-buff, activist, film-maker and academician. He is widely known for conducting immersive heritage walks around Delhi and bringing alive lessons from history through his impeccable art of storytelling and sharp sense of detail.

Sohail Hashmi carries the soul of Delhi inside him and knows the city in and out. Perhaps that is why, his heritage walks immerse you into long forgotten stories and secrets that make the city come alive.

As a filmmaker, Sohail Hashmi has worked on the scripting and production of various documentaries such as those on the pioneers of women’s education, history of Shahjahanabad, a series on the history of Urdu for the Ministry of External affairs among a host of other films. Apart from this, Sohail Hashmi served as the former Director of Leap Years- a creative activity centre for children and is also a founding trustee of SAHMAT. Recently, he has come up with a new series entitled Hindustan Ki Kahani on YouTube.

- As an academic, heritage enthusiast and filmmaker, you are widely known for the heritage walks that you have been conducting around the capital for several years and your ability to bring alive history for the young and the old. But what stands out about your personality is that you are a treasure house of memories, and the wide collection of your narratives and lived experiences, ignite interest and inquisitiveness in us all. Tell us about your own life trajectory and what shaped you into the person you are today?

Our parents came from two different backgrounds, on our father’s side there were freedom fighters and Islamic Scholars who came from an artisanal background that traced their ancestry to Kashmir in pre-17th century and to Delhi from then onwards. On our mother’s side there were poets and teachers who came from a background of Ulemas and Qazis of Kakori going back to the 14th century.

Except for our mother’s elder sister who was married already and lived in Bombay everyone else from our mother’s immediate family went to Pakistan. My mother came back to marry my father, who had stayed back, while his immediate family had also gone to Pakistan. So we grew up without any real aunts and uncles and cousins.

Our parents were a product of the freedom struggle, they were both strong willed people, they were political, they were hands-on and they were very creative, they loved books and were self-made. So despite growing up in rather difficult circumstances, economically speaking, we grew up amidst books, lively discussions, arguments and disagreements, we grew up listening to beautiful poetry and discussions on history, the struggle for freedom and about the communist movement. Among my father’s friends were poets, writers, critics, photographers and academics and we listened to their conversations and soaked in, as children in that age do, all the time.

There were 5 of us and they are listed here in descending order of seniority, Sabiha, I, Shehla, Safdar and last but not the least in anyway, is Shabnam, she is the youngest and the only one born in Aligarh. Now we are four, three sisters and I. Safdar was killed, by political goons on 1.1.1989, while performing a play in support of workers’ demands at Sahibabad. The play was performed by Jan Natya Manch, a theatre group that he had helped establish in 1973. Both Jan Natya Manch and Sahmat (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust) a platform set up by the creative community to fight for and defend creative freedom of artists, continue to carry forward the ideals for which Safdar lived and died.

Initially our father ran a furniture business started by my grandfather, the business collapsed in the aftermath of the partition. One of the reasons was an unstated boycott of Muslims. In 1952 my father went to Aligarh when Dr. Zakir Husain, the then VC of Aligarh University, asked him to set up a workshop at Aligarh University. My father set up the workshop and then pulled out to start his own business in Aligarh and that is the time, February 1955, when we shifted to Aligarh and stayed there till 1964, returning to Delhi after 9 years.

While we were still in Delhi, my mother completed her Montessori teachers training, while cooking, washing, cleaning and looking after three children while expecting Safdar. In Aligarh she decided to do her graduation privately and this she did in 1960 while running a full house, now with 5 kids and also entertaining friends and guests. In 1961, she got a job as a headmistress in Delhi in 1961 and it was on the strength of that job that we shifted back to Delhi in 1964 and our father also joined us in 1969. 1969 to 1976 was the only period in our lives when we were not living in a hand to mouth situation, our father bought a radio and a record player and three long playing records of his favourites Ravi Shankar, K L Saigal and Pankaj Mullik, the first “luxury items” in our house, we still did not have a gas stove and a fridge, which were considered a luxury, even in middle class homes, till then.

My parents probably had a year or less of some carefree time had a year or less when they lived a care free life right after their marriage and about two years before my father died, these were probably the only times when they did not have to count every paisa. He had paid off all his debts and could begin to plan a relaxed old age, it is then that he fell ill and died of Leukaemia in September 1976. I was 26 at that time and working for my M.Phil at JNU and we were back to square one.

After retirement my mother did her Masters with Persian as a subject at age 70, because she wanted to publish the Persian poetry of her father, she had carried the manuscripts with her all these years. She wrote a biography of Safdar in Urdu, it was published in Urdu and Hindi by Sahmat and an English translation was brought out by Penguin. She brought out the first volume of her father’s Persian poetry; she also wrote a training book for Montessori teachers, published by the SCERT, Delhi and was at 87 years of age working on her 4th book about her experiments in Nursery education, when she passed away on 1st February 2013.

Most of my childhood memories are about growing up in large open spaces in Aligarh from the time that I was about 4 years. My memories before that are of a really massive house in Kashmiri gate, it may actually not have been very large, because I was then very small and everything looked huge.

We never had money; the house where we stayed the longest in Aligarh had half a tin roof on two rooms for two years and the walls were never plastered. It boiled in the summers, got flooded in the rains and froze in winters, our books were kept under the covered part, the kitchen roof leaked and a large part of our parents’ collection of books was destroyed by white ants who were everywhere. We got water from a well outside and we had an old fashioned dry latrine.

We did not have many creature comforts but we had our books and a gang of friends and we invented our own games, games that did not require equipment. We staged plays and one of them had excerpts from Agra Bazar by Habib Tanveer. We put up a performance for all the elders of the compound and sold tickets for the show.

Whenever there was some money it went into buying books, both our parents were book lovers and this is something that all of us have inherited, both our parents were very creative and some of that has rubbed off as well.

By the time we had passed out of class 5, both I and my elder sister who was a year senior to me in school, had read and could recite extempore all the Faiz that had been published till then, we had read all Prem Chand, Krishan Chand, Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor, Manto, Ismat Chughtai, Faiz, Majrooh, Ghalib, Momin and Meer, most of it without understanding, and it is a long list. We also read translations of Gogol, Turgnev, Tolstoy and Gorky that were available, we had read Lu Hsun’s short stories and had read Sholokhov, Jack London, John Steinbeck, Nazim Hikmat, Ernst Hemingway and many more before we were in high school. The younger siblings too acquired these habits as they grew up.

We also read about the great struggles that the people of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos and also in Namibia, South Africa, Rhodesia, Palestine, Cuba, Chile, Nicaragua and El Salvador were fighting against Imperialism, Apartheid, Zionism and Neo-Colonialism. We read about the Spanish civil war and how writers like Hemingway went to fight against the fascist dictator Franco, we read about the destruction of the second world war and how artists, writers, poets, film makers, painters, actors theatre directors and many others had to escape from Germany in the face of persecution for being critical of the fascists.

And above all this we read about what British imperialism had done to our country and of the 200 year long fight that we waged to free ourselves from the colonial yolk.

We also read about the partition of the country and about the harvest of hatred that was 1947.

It was at Aligarh that we witnessed the first communal riot, the partisan nature of the PAC and escaped with the skin of our teeth while returning from school and remained locked-up at home for 45 days. Assimilating, reading, discussing and coming to understand the implications of all these, among many others, were the influences that shaped us.

The net result was that all of us had strong political opinions, except for Sabiha who had got busy teaching very early and then with brining up her children, the rest of us got politically involved in left politics and mass organisational work in different capacities.

Our family was always very cosmopolitan and this was something that we grew up with, my mother’s elder sister was religiously inclined but she could not understand why women were not allowed to pray in mosques and so, while still in school, she converted and became a Roman Catholic Christian, her motivation, women prayed in churches.

Marriages outside, caste, community, country etc. are common in my family for three generations now and we have had members of our family marrying among the English, Anglo Indian, American, Sri Lankan, French, Dalit, Jat Sikh and Rajputs aside from some marriages among Muslims as well, a few of them inter community like Sunnis marrying Shias, something that is as common or uncommon as Protestants marrying Catholics.

- We grew up in a secular inclusive and cosmopolitan environment and these were the values we inherited, we inherited an interest in the arts, in history, culture and architecture. We inherited a firm belief that all human beings are born equal and denying equal opportunities to people and any discrimination between people based on colour, creed, language, and place of birth is manmade, essentially unnatural and unjust and should be opposed.

We grew up reading about those who fought to create a just and free society and drew inspiration listening to stories about progressive writers and their struggles. Poets like Majaz and Wamiq Jaunpuri, the famous critic Ale Ahmad Suroor, Professor Nur–ul–Hasan, Professor Moonis Raza, who was later my guide at JNU and Hamid Allahabadi were friends of my father, so were Comrade Aftab, Comrade Jaikishan, Pandit Kamta Prasad and Bachchu Ji and Pyara Singh Sehrai, these were the people who contributed to giving us our world view. When we shifted to Delhi, we lost contact with many of these but then, Sehrai Ji, Saiyad Sajjad Zaheer and Habib Tanveer and others contributed to our education.

In college I got active in student politics and was one of the founders of the Students Federation of India in the early 1970’s, was drawn to Marxism and joined the Communist Party of India (Marxist), Shehla and Safdar too joined SFI but soon both moved into theatre and into Jan Natya Manch.

During the emergency, when I was working on my M.Phil, there was a police raid on the JNU campus and many of us were picked up, eventually about a dozen of us were arrested and sent to Tihar jail, after being released I had to leave the hostel since my scholarship was stopped.

I finished my M.Phil, registered for Ph.D. but gave it up after a couple of years to work full time with the CPI (M). I worked among the resettlement colonies of Delhi, with the head-load workers of Khari Baoli and Kamla Market and shop hands in Shahljahanabad for ten years, It is during this time that I learnt about the real condition of life of this large population, there were at that time more than 100,000, head–load workers in the grain, spice, lentil and pickles whole-sale markets of Delhi and not one of them had a permanent job. It is during this time that I married, my wife Kausar, too came from a political family, she finished her Ph.D. and began working, We had two daughters, both had started going to school and I was 41, when I started looking for a job in 1991

I drifted into the electronic media and joined PTI TV as a script writer, scripted most of the episodes for TANA-BANA, produced by PTI TV for Doordarshan. It is during research and writing for the series that I became aware, for the first time, of the phenomenal richness of the diversity of historical, cultural, linguistic, sartorial and gastronomical traditions of India and began to critique the narrow denominational terms to which our diversity was reduced. It is from here that I moved on to questioning the idea of Islamic and Hindu architecture and similar categories in cultural expression but that was a few years in the future.

From PTI TV, I went on to the National Literacy Mission as Media Advisor, from there to home TV, to Business India TV and to kingfisher.com. I launched my own media company to produce documentary films of which I have researched, scripted or produced more than 2 dozen, including Urdu Hai Jiska Naam, directed by Subhash Kapoor of Jolly LLB fame and produced by Meka Films for Ministry of External Affairs in 2003, shown on Discovery Channel for 4 years and the new series Hindostan ki Kahani in 12 parts, released on youtube recently.

Meanwhile I was asked by Rahul Bhandare, whom I had met through old friend Shubha Mudgal to help run a creative activity centre for children called Leap Years it is at Leap Years that the idea of heritage walks was born. It was only later that I realised that there were many others including Prof. Percival Spear, Prof. Narayani Gupta and institutions like the Delhi Heritage Society and INTACH that had been pioneers in the area. When I started the walks I was a novice, all that I had was the knowledge that I had acquired through the walks that our father had taken us on and had initiated us into how to look at buildings. I had that and I had what I had gleaned from Urdu texts on Delhi, the rest I have learnt from later research, the work of these pioneers and many others whose work is slowly turning heritage walks into a movement.

- As someone who has shown how pedagogic interventions can transform the way a subject such as ‘history’ is taught, what do you think obstructs creative teaching within most of our school classrooms?

I think the problem is with our method of teaching and this is not restricted only to the way we teach History but also how we teach every other subject. How many teachers have had the time from their classes, schedules, reports, endless meetings, to go out and explore new ways of making their classes more exciting and more challenging for the students.

Why we don’t do this is due to a number of reasons, we have divided knowledge into little water tight compartments and their connections to other branches of knowledge and to life processes have been severed, If a student wants to study Biology, Geography, History and literature together, there are no avenues for her in mainstream school education in India. Education is goal oriented and not designed to open the doors of knowledge, to encourage curiosity and the inquisitive streak and this fits in within a value system which discourages questioning and wants individuals to walk on a path that has been designed for them by their elders. The way the current dispensation wants to redesign all texts in humanities and the sciences to show that India had all the knowledge before anyone else in the world, is only going to add further to this myopic vision of knowledge.

Despite great strides having been made, in independent India, in all fields of History writing and teaching, including, curriculum content and teaching methodology and new avenues having been opened up for research. The findings are not even a part of undergraduate teaching of History in large parts of the country, so the less said about how history is taught in schools, the better.

The colonial approach of dividing history into Hindu, Muslim and British period continues. Even when they were using the very well written NCERT books most, history teachers continued to follow the colonial orientation, for example how many teachers asked the students to think about the time called Hindu period. There were powerful kings who were not Hindus, large part of the population were Jains, Buddhists, animists or those who followed other faiths. Similarly in the so called Muslim period, large parts of the country were ruled by non-Muslims. A large number of actual administrators, under the Mulsim kings like Mansabdars and other officials continued to be Non-Muslims and the overwhelming majority of the population was not Muslim.

Even if the period was identified as Hindu or Muslim period, because of the religion of the dominant king, then the British period should be called the Christian period. So our identities were reduced to our religious identities, but they had a secular identity, British. But we did not ask these questions.

In the name of History we continue to be bombarded by endless lists of kings, their reigns and their families, there is no talk of the people, their lives, their crafts, innovations, their cultural practices. Most importantly history in India is generally reduced to being a description of the rulers of Delhi, Agra and Lahore. There is little mention of the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas, Pallavas, Satvahanas, Gangas and the Chalukyas, the mighty empires that rose in the South, empires that ruled the oceans and traded with the far-east, the Middle-East and west Asia.

Some remarkable books have been written for school students by some of our finest historians and they bring in a whole lot of fascinating information on coinage, culture, the art of sculpture, trade, comparisons with contemporary developments in other parts of the world but most of this is never focussed on in the exams and so the teachers, desperate to finish the course in time and to revise, drop these sections and the bits that really make history interesting are never taught.

The kind of schedules we have, the load of the curriculum and the social and parental pressure to do better than everyone else, has taken the joy out of learning, the way out, to my mind is for schools to take children out more often, let the schools adapt a historical site, it could be a historical bazar, like Chandni Chowk, or Chawri, or the Badi Chowpar in Jaipur, an old Temple, a Sufi Shrine, a Mausoleum, an old graveyard or a step well. Let children work around the chosen site, try to peel off the layers, try to find out when and why it was built and why was it built where it was, what material was used, which direction does it face and why, what connection does it have with its surroundings and a hundred other questions. Let them ask and discover.

Reading grave stones in a cemetery in Landour near Mussoorie, I found out that till as recently as the late 1880s and even later, the age of marriage was rather low among the British, that death during childbirth of both the infant and the mother was not uncommon and that many of the young mothers were 18 or 19 years old.

So going out and exploring, trying to look at the inter-connections between things rather than as standalone phenomena is to my mind the best method of learning and also of enjoying what you are doing.

- The history of India has been in many ways, the history of cultural and religious exchange and diversity of languages, cultures, traditions, culinary and sartorial preferences and religious practices has been an integral and essential part of the idea of ‘Indianness’, with there being no uniform, homogenous and all-pervading notion of being ‘Indian’. The dominant discourse of nationalism today, however asserts a civilizational uniformity and denies religious/cultural diversity as the essence of India. How do you look at this emergent political trend?

When we talk about diversity we only talk of the religious diversity and present that as a great achievement of our civilisation, but rarely do we talk of the phenomenal linguistic, ethnic, historical, social and cultural diversity of India.

Diversity is a precondition for development of civilisation, according to the Census of India 2011 there are 19500 spoken languages in India out of these 121 languages are spoken by more than 10,000 people, the remaining languages are spoken by fewer numbers, almost all are animist Tribal communities out of these 19500 language only 22 languages are included in the eighth schedule of the constitution of India. The 22 languages represent a very high percentage of the mother tongues spoken by our total population, but they represent a very small proportion of our cultural and linguistic diversity. It is this diversity that defines the myriad hues that enrich our cultural plurality.

In any case this idea of India as something that has always existed is not entirely true, principally because the idea of nation is a product of the 19th century and we were first united under one rule, when the British had taken over the entire country, either directly or because most of our great fighters cut their own deals of submission with the British. Historically we were always fighting our neighbours, like feudals everywhere. Each Raja or Rana or Maharaj or Maharana who could gather together an army, would go and attack a weaker neighbour or they could band together to attack a strong adversary and so it was that the Nizam, the Wodeyars and the Marathas supported the British in their fight against Hyder Ali and Tipu. When Rani Chenamma of Kittur in Karnataka stood up against the British, no one came to help her and it was the same with Siraj-ud-Daulah in Bengal.

The 1857 revolt of the soldiers of the Bengal army became a struggle for freedom when the dispossessed peasants of UP and Bihar rose up in support of the Sepoys and of their deposed rulers like Hazrat Mahal and Birjees Qadr in Awadh, Nanaji of Bithoor, Kunwar Singh in Bhojpur, Bahadur Shah Zafar in Delhi and Rani Laxmi Bai in Jhansi and a few others. All the other rulers, the overwhelming majority, cut their own deals with the British and sided with them. There was no consciousness of India under attack by outsiders, because there was no consciousness of India, each ruler considered that he was the sovereign of his nation. And there were hundreds if not thousands of them. The loyalties of the subjects were also to their own local Satraps and that is why one sees little anti British agitation in the 19th century in areas where the ruler was with the British. Most of the action was in areas where the people saw their dislodged rulers resisting the British

All the rulers of Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Garhwal, the Dogras of Himachal, the Maratha, the Nawabs of Rampur, Bhopal and Hyderabad were with the British. In fact virtually nothing happened to the South of Nagpur and very little happened between in the present Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, so one can clearly see that the idea of India as a united entity does not exist till as recently as the mid-19th century. The idea of India as a unity is the product of our struggle against an alien ruler who was out to destroy everything that we had. For the first time there was a ruler who had nothing in common with us, he spoke, dressed, lived, ate and entertained totally differently and thus for the first time there was a ruler who controlled the entire territory that we now know as the south Asian sub-continent, he was different from us and was looting and destroying us.

The leaders, who came of age in the 30 years after 1857 was crushed, were the ones who developed the idea of India as a nation in servitude, a land and its culture was under threat by the British and so our identity as a nation was formed in distinguishing ourselves from them and fighting them. The contrast was so sharp that we were able to forget our differences and unite against the common enemy because we saw ourselves as different in every way from our rulers, so an Indian identity was created through the exclusion of the Firangi, the non Firangi were together in this fight, this idea evolved in the 1880s and 1890s.

Unfortunately even in the evolution of this idea we were not united, three ideas of India emerged, A Hindu Rashtra where Muslims and Christians will live as subordinates, was first articulated by Savarkar in 1937, the counter to this emerged in 1940 when the Muslim League raised the demand for a separate country for Muslims, distinct from these two was the mainstream of India and its political leadership that dreamt of a united India where everyone had equal rights and we lived together with all our diversities.

This is the idea of India that was born in the struggle against the British, this is a modern idea and this is the only way in which an India can survive. This effort to define India as a cultural unity is the problem, because what is being privileged is the idea of India as imagined by a minuscule minority.

The idea of India being projected today, is an idea based on exclusion of all Minorities, Dalits, Tribals, Non-Hindi speaking and Meat-Eating people. The idea of India that is systematically being pushed is the idea of India as imagined by a right-handed, upper-caste, fair-skinned, north-Indian, heterosexual male and his idea excludes everybody who is different from him, with the exception of his immediate family and those like them and of course docile, obedient, fair skinned girls who he and the likes of him will marry, to serve and to procreate, unquestioningly. This unfortunately is the horrible reality that is unfolding before us.

- As someone who has extensively worked on Delhi and its historic flavours, what do you think has characterised it over the years and why do you think it has always been the centre of power from the British, to the Mughals and even in independent India ? How do you think Delhi has changed in terms of its acceptance of people from the different states of India who flock to it for lucrative opportunities and why do you think that despite its problems, it has continued to remain a city that boasts of an air of freedom and cosmopolitanism?

In fact Delhi does not have a very long history as a city; it is believed that it was ruled by the Tomars who were succeeded by the Chauhans. The last of the Chauhans, Prithvi Raj was defeated in the 2nd battle of Tarain (in present day Haryana) by the Afghan Mu’izz ud Din Ghuri. The capital of Prithvi Raj Chauhan was, however Ajmer and Mu’izz ud Din Ghuri ruled from Lahore as did his governor Qutub-ud-Din Aibak, it is only in the time of Altamash that Delhi becomes capital and remains the capital through the reigns of the Mamlook, Khalji and Tughlaq dynasties, except of course for six years (1329-1335), during the reign of Mohammad Bin Tughlaq when the capital was located at Deogiri in Maharashtra before returning to Delhi.

The second Lodi King Sikandar Lodi, took the capital to Agra, Babar also ruled from there, Humayun brought it back to Delhi. With Akbar, Agra became capital again and the capital returned to the new city Shahjahanabad in 1648, the capital moved out once again in 1859 to Calcutta, was brought back in 1912 and has stayed put since then, first as the capital of British India and then the capital of independent India.

All cities, if they are cities, are a result of migration. Cities are a result of mixing, native populations do not create cities, migrants do. If a settlement continues to grow naturally, no matter its size, it remains a village. It is through migration that new crafts, skills, trades, fabrics, music, food, languages, spices, new building techniques and new architecture are introduced to the existing settlement and all this begins to change and develop into new forms and the settlement begins to grow into a city. It has been the same with Delhi, if you were to remove all the migrants from Delhi, you will be left with a large number of scattered villages, inhabited by peasants – Jats, Gujars, Sainis a few Brahmin families and the so called, ‘lower orders’ with their traditional crafts and agricultural practices.

From the time of the Tomars, about the 10th century onwards, but more notably from the late 12th century, the place that we know as Delhi today begins to receive an almost unending stream of migrants, who make this place their home. There were Soldiers of fortune, war lords and there were those who wanted to establish new empires or to expand the territories they controlled. In the wake of the marching armies and at times independently of them, came traders, Sufis, scholars, mendicants, proselytisers, musicians, weavers, smiths, carpenters and those practicing other crafts, they spoke Persian, Turkish, Uzbek, Tajik, Arabic, Pashto, Dari and mixed with the speakers of Telugu, Marathi, Gujarati, Punjabi, Multani, Sindhi, Makrani, Mewari, Marwari, Hadauti, Saraiki Haryanvi, Braj, Rohelkhandi, Baghelkhandi, Awadhi,Bhojpuri, Bangla, Oriya and others.

All these indigenous languages mixed with the languages of the new arrivals, in the market place, in the construction sites, in the army camps, in the shrines of the Sufis, in the workshops and in the Caravanserai and gradually, by the early 14th century the language of Delhi – Zaban e Dehli or Hindavi began to develop. This mix has continued to enrich Delhi across centuries, through all the dynasties that ruled Delhi and even when we were colonised.

Delhi ceased to be capital for a little over half a century and then the capital shifted back to Delhi in 1912; many offices were shifted from Bengal. Tamil and Marathi speaking officers from the presidencies of Bombay and Madras also migrated to Delhi and with each came their food, their attire, their places of worship, their music and their dances.

After Independence and partition, Delhi received a large influx of what were then called refugees, but 70 years later are Pucca Delhiwallas.

The influx changed the language, culture, food habits and demeanour of Delhi. The population of Delhi was 900,000 before independence; it fell to 600,000 because of the killings and migration and then rose by end 1948 to 1,400,000. This was an influx of 800,000 in less than a year and a half. A majority of the population in Delhi in 1948 were now speakers of Punjabi, Multani, Sindhi and other languages that were spoken in the region which was now Pakistan. 70 years later a majority of the descendants of those migrants now speak Hindustani, which is now rapidly acquiring a lilt that is clearly, Awadhi, Purabi and Bhojpuri, since roughly 33% of the current residents of Delhi hail from East UP and Bihar and have migrated in the last 30 years or so. This is how a city changes and still retains its character.

A city cannot close its doors to migrants, because a city is nothing but a space and an ethos created by migrants. A city if it wishes to survive cannot do so without this constant injection of fresh blood. Up to now, Delhi has never engaged in the kind of politics that some other cities are known for. Those who try to shut out the migrant or do not create a welcoming environment for the migrant will cease to grow and will eventually collapse. If those millions who have had to go back to their villages, because our cities did not care for them, will have to be welcomed back, the cities will have to fall on their knees to welcome them back or the cities will cease to be what they were.