And one of the elders of the city said, “Speak to us of Good and Evil.”

And he answered:

Of the good in you I can speak, but not of the evil.

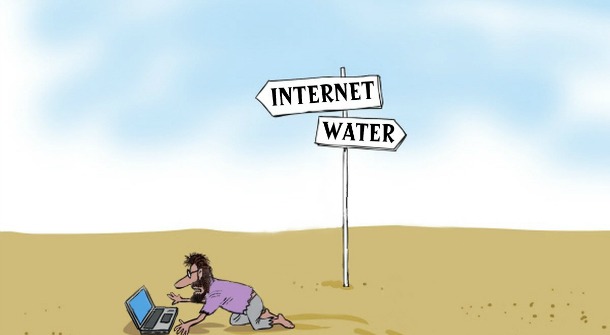

For what is evil but good tortured by its own hunger and thirst?

Verily when good is hungry it seeks food even in dark caves, and when it thirsts, it drinks even of dead waters.

You are good when you are one with yourself.

Yet when you are not one with yourself you are not evil.

-Khalil Gibran

The poem begins with an elder asking the prophet to speak about good and evil. The prophet responds by saying that he can only speak of good, because evil is simply good that has been corrupted by its own hunger and thirst. The prophet then goes on to say that when good is hungry, it will seek food even in dark caves. This means that when we are driven by our desires, we may be led to do things that are not good. However, the prophet also says that when good is thirsty, it will drink even of dead water. If we are in a state of desperation, we can still find the strength to do good. The prophet concludes by saying that you are good when you are one with yourself. When you are living in alignment with your true nature, you will naturally do good things. However, when you are not one with yourself, you are not evil. So, if you do bad things, it is because you are lost and confused, not because you are inherently evil. The poem “Good and Evil” is a reminder that we are all capable of doing good, even when we are driven by our desires or when we are in a state of desperation. Hence, we should not judge others too harshly, because they may simply be lost and confused. We may be lost and confused because we are not aware. Good and evil are not absolutes, they are not black and white. It lies within all of us. Becoming aware by understanding the factors of good and evil, right and wrong that influence our action, we can take steps to cultivate a more inclusive and open-minded mindset. This includes acknowledging the role of social environment of oneself that includes cultural norms and upbringing in shaping our beliefs. We can start by acknowledging our own biases and prejudices that drive us to stereotype people. We are better equipped to challenge them and prevent them from leading to discriminatory behavior.

In our last discussion we have seen the complex process by which prejudice develops, often beginning in childhood. Social structure, Cultural influences, social interactions, and personal experiences all contribute to the formation of biased attitudes. We have seen through the lens of different theories – Social Identity theory, Social Dominance theory and Realistic Conflict theory. Today we will see how Children develop prejudice and forms moral reasoning at a young age. These two processes are intertwined, and they can influence each other in complex ways. Group identity is also a key factor in prejudice, as we have seen in previous article that children tend to favour members of their own group over members of other groups. Let’s explore this topic in more detail.

Analyzing the Interplay of Prejudice, Moral Reasoning, and Group Identity in Children:

During my field practice at an Anganwadi, I did research on how young children understand and learn values. To understand this, I created situations where children had to make difficult choices. I watched how the children responded to the situations I created. I asked the children why they made the decisions they did. This helped me to understand their thought processes and how they were making decisions. In my class, there were 17 children from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Some were from very poor families, while others were from middle-class families. One day, I wanted to observe whether children would choose friendship over winning a game. I planned a game and divided the children into two teams, each team had children from poor and middle-class families. I wanted to observe if they would play to win the game with their own team members or if they would prioritize maintaining their friendships with children from the other team. What would influence their decisions? What matters more to them: winning the game or their friendships? How can a 5-year-old child make such a decision? Interestingly, the result showed that 70% of the children chose to intentionally lose the game in order to support their friends. They cheered for their friends even when they were on the opposing team. While they felt a bit sad about losing the game, they were also happy for their friends. What motivated them to play for their friends and with classmates from a different group? Could there be some biases between students from both groups that influenced their moral choices? In our previous article, we explored how biases and prejudices can contribute to discrimination and exclusion. Let’s see what is happening in the case of children.

In above example there are two social groups have been formed among these young children. One is of poor family background, and another is middle-class. This is likely because they have different experiences and values based on their family’s socioeconomic status. They already have developed some assumptions about another social group. For an example Poor child may think that middle-class kid is mean. Maybe because children may have had negative experiences with middle-class children in the past, or they may have heard negative things about them from their parents or other adults. This can lead to them developing negative stereotypes about middle-class children. Because of their negative stereotypes, the poor children may not be willing to help their team in a game if there are middle-class children on the team. They may instead choose to help their friends from the same social group. The children’s group identity, or their sense of belonging to a particular group, played an important role in this situation. The poor children’s negative stereotypes about middle-class children led them to not help their team in the game. This happened vice versa in the case of Middle-class child. This shows how group identity can influence how people behave. And also, their prejudices can have a significant impact on their moral judgments. The intricate interplay between prejudice, moral reasoning, and group identity in children’s development is a multifaceted phenomenon that has been explored through various theoretical perspectives. Recent research has shown that children’s decision-making processes are not influenced by moral principles or cultural norms in isolation. Instead, they are influenced by the combination of these factors. This combination of moral principles and cultural norms is what shapes children’s social reasoning and the development of prejudices.

Social-Domain Theory and Moral Reasoning:

The Social Domain Theory provides an insightful perspective on how moral reasoning intersects with the development of prejudices. This theory suggests that children possess distinct cognitive domains related to the self, the group, and morality. From an early age, children’s judgments involve weighing moral considerations, group norms, and personal goals simultaneously (Turiel, 2006). For example, in your experience at the Anganwadi, when the children were divided into mixed groups, they had to decide whether to play for their own team or support their friends on the other team. In terms of the theory, they were thinking about being fair to their friends (the moral part), following what their social group expected (the group part), and maybe wanting their friends to be happy (the personal part), all when deciding how to play the game.

Social-cognitive development research has revealed that as children grow and interact with their environment, they engage in a variety of cognitive processes that help them understand and navigate their social world. These cognitive processes involve making judgments about various situations, people, and actions. These judgments are guided by different types of considerations, and researchers have identified three distinct social domains that play a crucial role in shaping children’s thinking and decision-making:

Psychological Domain (Self-related Considerations):

The psychological domain relates to aspects about oneself and personal choices that aren’t necessarily linked to moral concerns or societal rules. This involves ideas of independence, individual wants, and personal aims. In this area, children focus on their own emotions, thoughts, and needs. It also includes beliefs about who they are and why they do certain things.

As I mentioned earlier, I set up situations to observe how children would react. For instance, I placed an attractive eraser in the classroom secretly, to see what the children would do. Would they give it back to the teacher or keep it? In this case, few children decided to keep the eraser. Perhaps they don’t fully understand the concept of stealing; they just liked the eraser and wanted to keep it. They mentioned that they really liked the eraser, so they just kept it. This example illustrates how our feelings can influence our moral choices.

On the other hand, a few children returned the eraser to the teacher. When asked why, they mentioned that they did it because they consider themselves good kids; it’s not theirs, so they gave it back. This showcases their self-identity as being good and their feeling and aspiration to maintain that good kid image. Such image is a social construct. Here “good” is based on norms and considerations.

Societal Domain (Group Norms and Regulations):

The societal domain focuses on the rules, norms, and regulations that are established within a group or society. Children learn about the expectations and standards of behavior within their cultural and social context. They understand that certain actions are considered appropriate or inappropriate based on the norms of their community. Portraying oneself as virtuous is highly valued in our society. Frequently, an individual is labeled as “good” based on their deeds, specifically how well those actions align with societal standards. This is evident in a classroom scenario where children who adhere to regulations are often praised as “good boys” or “good girls.” Traits such as being reserved, complying with instructions, and attentively listening to the teacher contribute to this perception. These guidelines significantly sway moral choices as well. For instance, in the earlier mentioned case, the boy’s desire to uphold his identity as a “good boy” motivated him to return the eraser.

Moral Domain (Principles of Fairness, Equality, Rights, and Welfare):

The moral domain involves principles related to fairness, equality, rights, and the well-being of others. Children develop an understanding of what is morally right and wrong, and they begin to form their own moral judgments. This domain includes concepts such as empathy, compassion, and the recognition of the rights of others. For instance, a child gave more importance to friendship than winning a game. It shows their emerging sense of fairness and empathy for the member of their social group.

Importantly, these three domains are not isolated from each other; they coexist and interact in children’s decision-making processes. As children encounter various situations, they consider information from all three domains to make judgments and decisions. For instance, when faced with a moral dilemma, a child might weigh their own desires (psychological domain), societal norms (societal domain), and principles of fairness and rights (moral domain) before arriving at a decision.

The coexistence of these domains highlights the complexity of children’s cognitive & Emotional process of Reasoning & decision-making. Their growing understanding of self, society, and morality is intertwined, and these domains collectively shape their perceptions and actions. Children consistently consider their own feelings and social conventions while making any Moral judgements. This is very dynamic process. We can see difference in their behaviour in different situations. For instance, once I plan an activity where the children from both groups have to work together to build a structure using building blocks. In this scenario, the children bring their own ideas and beliefs about how to build the structure. Some might think their way is the best, while others have different thoughts. This is like the mix of ideas we talked about, where kids think about what they know, what their group thinks, and what they personally believe is right. As they work together, they start to see that both groups have good ideas. Maybe the kids with fewer resources have clever ways of making the blocks stable, while the others have creative ideas for decorating the structure. This is where the concept of combining viewpoints comes into play. The children realise that by bringing their different ideas together, they can build something really cool.

Through this activity, the kids are learning that working together and understanding each other’s ideas is important. They’re also learning that just because someone is from a different group doesn’t mean their ideas are less valuable. This relates to the part about prejudices – when kids see the value in each other’s ideas, they start to break down biases and prejudices that might have existed between the groups. So, this Anganwadi experience shows how combining different thoughts, understanding each other, and valuing everyone’s contributions can lead to a more understanding and harmonious environment, as I explained above. This approach helps the kids grow up with open minds, ready to make a better future where everyone respects and supports each other. This make also help in tailoring bias reduction. This awareness will help us to create a foundation for a more compassionate and tolerant society. As Prophet says that evil is simply good that has been corrupted by its own hunger and thirst. We can overcome evil by being open to new ideas, learning from others, and being true to ourselves. When we do these things, we can create a more understanding and compassionate world.

Tarannum Shaikh is Research Associate, Azim Premji University, Bhopal.