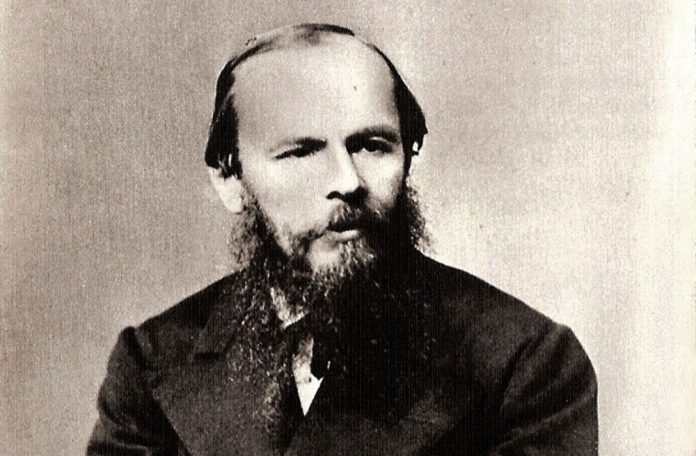

Perhaps some of the best teachers I have had the privilege to engage with in these past few months of confinement owing to a pandemic raging outside have been books and the authors who have created those particular universes within the books. While reading has been an escape for me since my childhood, engaging with books at this time has taken on a significance that cannot be described as an avoidance of reality. My friends and I decided to read The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky at this time precisely because the reality of our lives and that of our fellow human beings across the globe needed an understanding that went beyond the glibness of headlines and glamour of entertainment.

During the course of our reading this book together, my fellow book-club members and I have discovered the joys of approaching this reading differently, respecting each other’s views equally, revelling in the beauty of the author’s creation and arguing over the philosophy presented by its characters, and the world-views they carry. The process itself has been a teacher about which I am still learning. Yet the discussions have yielded sweet and nourishing fruit from which I can share. It is from these conversations among friends that I draw out a thread to share with you, of a teacher who offers us a fresh view on what an education for peace, dialogue and justice could look like. This is the character of Father Zossima, the elder at a monastery where one the Karamazov brothers joins as a novitiate.

There are, of course, many scholarly articles and books written on the themes and characters in Dostoevsky’s works, and this piece does not aim to belong among them. I write this more as an anecdote, an experience of conversing with a teacher over the course of a journey. These are some of the snippets from my ongoing conversation with Father Zossima as I go about my days.

The Peasant Women and Justice

It is no doubt Dostoevsky’s genius that he places the practice of justice as offered by Father Zossima to the peasant women just before a detailed discussion among the key characters on the State’s view of justice towards its citizens. The love that animates Zossima’s engagement with the women stands out in relief against the State’s approach of excluding the criminal from society, as if by removing the criminal, all other citizens will be purified of the polluting presence of crime.

Zossima’s claim that we are all responsible for the sin/crime that one among us commits speaks to me at this time particularly, when we choose to ‘other’, ‘call-out’ and are always on the lookout to blame and shame anyone who does not agree with our political views; this form of justice being performed both on social media and in the lynchings on the street with horrifying regularity.

Zossima’s acknowledgement of the peasant women’s grief – at the loss of a young child, anger against ill treatment by one’s spouse and acts of vengeance as a consequence are all received within this appreciation of the human condition, an appreciation that stems from love and leads to an ownership of mutual responsibility.

The Monk’s Vocation and Dialogue

From his death bed, Zossima entreats his fellow monks and priests to worry less about the ‘smallness of their means’, but rather to spare just an hour in the week to spend with their community, opening up their homes and reading texts together, especially with children. This is planted in the firm belief that the peasant is able to comprehend the mysteries of the universe and the simple affection among fellow human beings as captured in these holy texts, in equal measure, for the peasant has experienced life at its most difficult and yet retained their dignity, ‘even after two centuries of serfdom’.

This view of the other as a person and not an object, an I -Thou relationship rather than an I – It relationship is at the heart of the practice of dialogue. Zossima’s claim that ‘equality is to be found only in the spiritual dignity of man’ inherently prevents the violence we inflict on our equals when we treat them as inferior objects – to be either used as resources or pitied into submission. These months of confinement, of being in close proximity with members of one’s family, the chafing that we have experienced and inflicted within these relationships bring home the significance of this claim of Zossima’s with painful frequency.

The Wedding in Cana of Galilee and Peace

Throughout the telling of Zossima’s life and acts as an elder, Dostoevsky peppers the narrative with criticisms being levelled against him by his fellow monks. One of the chief complaints against Zossima is his joy and celebration of life – which is seen as unseemly for a monk who is meant to live a life of abstinence and severity. In a beautiful passage, Dostoevsky employs a reading from one of the gospels in the Bible that speak of Jesus converting water into wine to highlight this very characteristic of Father Zossima. Dostoevsky shows Zossima participating in the wedding festivities where Jesus is performing this miracle. This helps us appreciate what communion would look like, where all the guests are ‘drinking the new wine, the wine of new, great gladness’. The writer D.L. Mayfield identifies ‘shalom’, which is commonly understood to mean peace, as the flourishing of all, especially the marginalised, the misunderstood, the maligned within a community. Nearly a century and half before her, Dostoevsky had already identified through the life of Father Zossima what this flourishing would look like.

Father Zossima gently nudges me in our conversations to not only engage in the work of justice and dialogue as he practises them, but also to revel in another’s company, to learn how to relate with another, recognising their dignity and enjoying the time we have been offered on this earth with each other. And for these reminders, I am truly grateful.

Roopa Rathnam is an eminent Scholar working on feminism and religion with special reference to Pandita Ramabai’s life- trajectory and contributions.