Letters and Biographies: Beyond Textbooks

Meaningful learning requires pure joy—no burden of completing the syllabus, no fear of examinations. It is possible if the child is encouraged to see beyond textbooks, and read what is not in the syllabus, yet so deep and profound. While referring to Nehru’s letters and Gandhi’s autobiographical reflections, the author pleads for an innovative pedagogic possibility.

By Avijit Pathak

Textbooks and examinations centred on the solidity of hard information dominate the culture of learning; teachers disseminate the information stored in the prescribed texts which students memorize through all sorts of disciplinary practices, and at the end of the day their ‘ knowledge’ is measured in terms of exam results. We all realize that there is something pathological about this form of learning. It restricts; it closes the mind; it deprives the culture of learning of the spirit of exploration and self-discovery. This is not to suggest that textbooks are necessarily bad. There are innovative textbooks. However, the point is that even a good textbook is limiting because there are multiple sources of knowledge, and it is important to make the child exposed to these possibilities.

Take, for instance, the remarkably beautiful art of letter writing: how letters—deep, penetrating letters—sensitize us, enable us to understand the trajectory of life, history, culture, politics and society. An average textbook in history/social science informs the child of, say, Jawaharlal Nehru, the role he played in the freedom struggle, and some of the ‘socialist’ measures he undertook as the first Prime Minister of the country. Granted, it is important information. But Nehru’s letters would make the child understand the richness of his thought, his mind. It is more than quick exam answers; it is the real substance. February 13, 1933—Nehru wrote a letter (The Coming of Socialism) to his daughter from the prison. See the letter—so rich in thought, information, emotion and philosophic depth. True, the successes of capitalism ‘dazzled people’, but with absolute sensibility Nehru was trying to arouse his daughter’s imagination, and taking her to those historic moments of industrial capitalism in England: “The conditions in the factories in England were appalling, the workers’ houses or huts were even worse. There was great misery among them. Little children and women worked incredibly long hours. And yet all attempts at improving these factories and houses by legislation were opposed by the owners.” But you cannot kill human possibilities. Nehru wanted his daughter not to forget: “Meanwhile, there arose a man among the factory owners of Manchester who was a humanitarian and who was pained at the shocking conditions of the workers. This man was Robert Owen. He introduced many reforms in his own factories and improved the condition of his workers. Owen’s idea was to have workers’ cooperative societies, and that workers should have a share in the factories. His influence, during his time, was great, and he gave currency to a word socialism, which

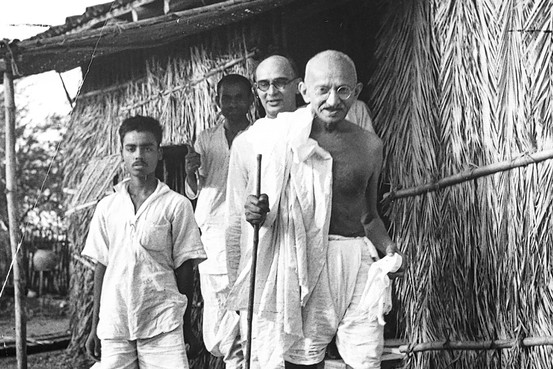

Likewise, good biographies are equally inspiring—the child can overcome the monotony of textbooks, their inherent impersonality, and enter a new world. Look at, for instance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s Autobiography. Yes, textbooks inform the child of Gandhi’s contributions to the freedom struggle: a set of facts chronologically arranged—almost the right kind of material for the television quiz contest! But imagine you are introducing the child to a chapter—say, The Magic Spell of a Book—from Gandhi’s Autobiography. What a revealing travelogue! It was South Africa; Gandhi was in the train; and Johannesburg to Durban was a twenty-four hour’s journey. A friend called Mr. Polak had given him a book to read. It was John Ruskin’s Unto This Last. Gandhi read it. See the way he described the entire experience. “During the days of my education I had read particularly nothing outside textbooks, and after I launched into active life I had very little time for reading. I cannot, therefore, claim much book knowledge.” That was his honesty, his courage to confess. However, Ruskin changed him. “The book was impossible to lay aside, once I had begun it. It gripped me…. I could not get any sleep that night. I was determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book”, wrote Gandhi. What did Gandhi learn? And why did he want to change his life? To quote him:has since captivated millions.” The letter became a document of history—yet, so personal, so intimate and touching. Indeed, these ‘glimpses of world history’ emerged as a beautiful narrative. True, Nehru reminded her daughter that “the present world with all its selfishness and violence is far removed from this fine ideal—perfect freedom for everybody, each person representing the other, unselfishness all round, and willing cooperation.” But then, it also revealed Nehru’s mind—his inclination to the ethos of socialism, his empathetic understanding of Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropatkin, and the historic journey from the ‘anarchist’ ideal to Karl Marx’s ‘scientific’ socialism. Moreover, a letter of this kind is immensely pedagogic; it is free from the hardness of textbooks. With conversation and communication begins true learning. And it did not remain limited to his daughter because a great letter, precisely because of its art, could unite the personal and the historical.

“The teachings of Unto This Last I understood to be:

- That the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

- That a lawyer’s work has the same value as the barber’s, in as much as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work.

- That a life of labor, i.e., the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman is the life worth living.”

Yes, that was the magic spell of the book: “I arose with the dawn, ready to reduce these principles into practice.” If a child is encouraged to go beyond textbooks, and feel the fragrance of a biographical note of this kind—written with such clarity and lucidity, it is bound to make her realize what kind of person Gandhi was, the way his thought and practice, be it spiritual socialism or satyagraha, evolved, the way he opened the windows of his mind, and continued to learn, unlearn and evolve till the last moment of his earthly life. History/social science would acquire a soul; and for the child, Gandhi, far from existing as a statue, would become an intimate companion. It would be easier for her to make sense of Gandhi’s travelogue—from Champaran to Ahemadabad, from Noakhali to Delhi.

The point I am trying to plead for is that there are immense possibilities; and if a teacher keeps her pedagogic option alive she can take the child to a new world of understanding. It should not be forgotten that we are living at a time when children are oppressed; the bounded world of textbooks, rote learning, the tyranny of coaching centers, exam results, and all sorts of forced activities (for keeping the child busy) like French class, swimming and horse riding make it almost impossible for them to experience the joy of reading, learning and self-discovery. It is, therefore, important that a creative teacher/parent realizes the need, and exposes the child to another world in which, for instance, Nehru writes a letter to his daughter, and Gandhi narrates the experience of reading a book, a world in which there is no fear of examinations, there is no tyranny of multiple choice questions; instead, there is pure joy in reading, learning and unlearning; there is deep understanding of life, culture, society and politics. And imagine what it means to a child rediscovering Nehru’s or Gandhi’s mind, particularly when the cult of narcissism murders the likes of Robert Owen and John Ruskin, and in the hyper real word of media spectacles the ‘leader’ of the nation charms the affluent NRIs through his theatrical gestures! Who knows the child, with the flash of awakening, might switch off the television set, and speak loudly and clearly: “The Emperor is naked”?