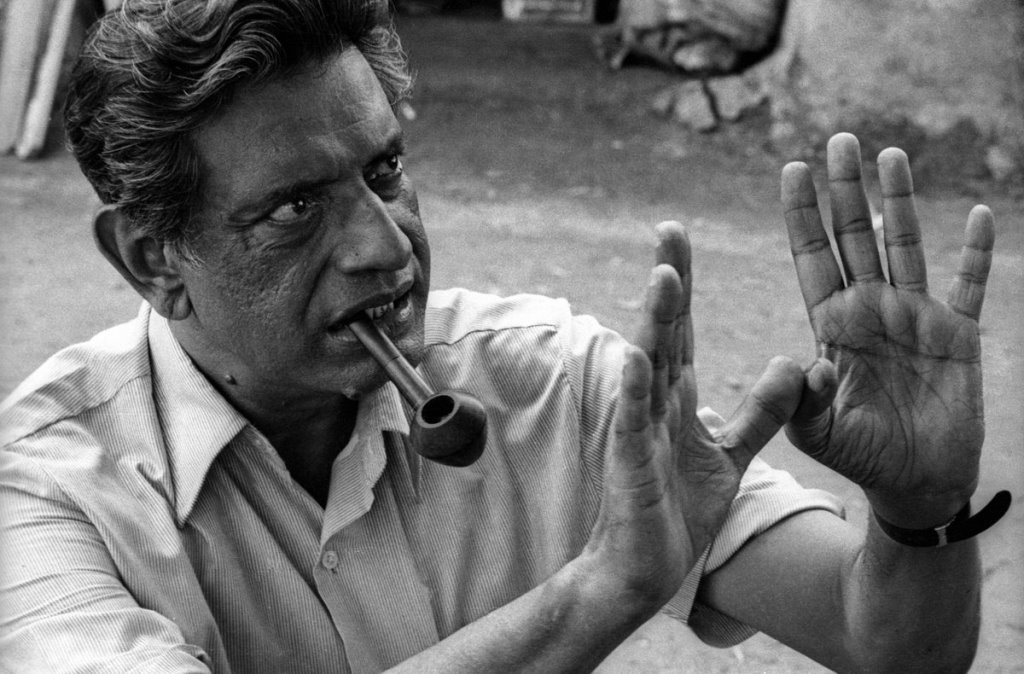

Mahanagar was released in 1963. I was merely six year old. I saw the film much later. And today when I see it again I feel that a piece of great art is never exhausted; it continues to enchant us. From 1963 to 2018: Indian society has undergone a dramatic transformation in terms of its polity, economy, social relations and middle class aspirations. Yet, despite these changes, there is something remarkable in the film—particularly, the beauty and complexity of conjugal relationships, the experiential domain of a caring mother/wife/daughter-in-law undertaking a journey from home to the world, and the delicate task of living with honour and dignity in a family severely affected by economic hardships. As a gifted filmmaker, Ray is always subtle, never loud. His camera, scrip (based on a short story by Narendranath Mitra) and music create a splendid poetry of visual narrative on celluloid. Love and pain, joy and anguish, broken communication and ultimate surrender: the rhythm of everydayness of a lower middle class family in a big city enters our souls.

No textbook feminism, please

I know that I am writing about the film on International Women’s Day. Well, as a university educated person, I feel tempted to use feminist theories. However, I would resist this temptation; instead, I would allow myself to be receptive, and learn from every movement of Arati : a lead character in the film aesthetically portrayed by Madhabi Mukherjee. No, Arati is not a feminist in a way a standard textbook of sociology of gender would define it: someone perpetually contesting a socially constituted gender identity of a caring mother/wife comfortable with the chores of domesticity, and seeing the possibility of emancipation in absolute autonomy. Yet, what is remarkable about Arati is her inner flowering: her domesticity and courage, her agency and humility, her love and spirited work. Her heart aches as she sees her husband’s everyday struggle: working in a private bank with a minimal salary not sufficient to maintain the expenses of the family. It is difficult to buy even a new spec for his old father—a retired schoolteacher. This ethic of care leads her to think of taking a job and contributing to the economic stability of the family. Yes, Subrata—her husband (acted by Anil Chatterjee)—finds an ad in a newspaper for a ‘salesgirl’ in a company; he persuades her to apply for the job. And she gets it.

However, this journey is not easy, particularly for a woman who cares for everybody in the family—her child, her in-laws, her husband and his younger sister (Jaya Bhaduri). With a cultivated art of empathy, Ray captures the psychic turmoil of Arati as she begins her journey to the office. How difficult it is to leave the child who finds it difficult to bear the separation from mother; as she sees her struggling/tired mother-in –law working alone in the kitchen something happens to her. Ray communicates it through Madhabi’s eyes. However, the harsh economic reality takes her to the streets of the city. As a ‘salesgirl’, she visits affluent households and persuades the housewives to buy the products of the company in which she works. With absolute sincerity, Arati finds herself in her work; her colleagues love her; her boss begins to trust her.

A month passes. She gets her salary, buys gifts for everyone in the family. As she approaches her father-in-law, gives him a packet of fruits, and a part of her salary, he refuses to receive it. He calls himself ‘old fashioned’; it is not possible for him to accept a woman going outside home for earning money; it is beneath his dignity to accept money from his daughter-in-law. With absolute fineness, Ray shows the patriarchal notion of ‘honour’ in a middle class bhadralok family. Arati absorbs everything—this ‘cold war’, some sort of extra curiosity on the part of her otherwise caring husband about what she does in her office, about her boss. In her husband’s changing gaze or his taunting words, she begins to find some sort of rapture. And yes, the constant pain that her child experiences in the absence of his mother when she goes to office makes her realize the chain of social/psychic/existential challenges patriarchy poses before a woman seeking to balance the home and the world. No slogan, no rhetoric, only deep understanding—this is what Ray is all about.

Yes, this woman with grace and silence (her traditional markers are obvious—she is uneasy with English, she even suggests ‘homeopath’ medicine to her snobbish/upper class client for her child suffering from cold, and above all, the use of lipstick which her ‘Anglo Indian/stylist colleague Edith suggests makes her perpetually hesitant) is also a woman filled with courage, conviction and a spirit of rebelliousness. Even though her boss trusts her, plans to give her more responsibility and even increases her salary, she does not hesitate to protest and eventually resign when her boss insults Edith and accuses her of false charges. This ‘impulsive’ woman does not hesitate to give the resignation letter to her boss even though she knows that her husband has already lost the job, and severe economic crisis is haunting the family. Arati’s agency is convincing; and I would add that it makes Mahanagar a great piece of cinematic text on love, power and femininity.

Return of the catharsis

Anil Chatterjee as Arati’s husband has done justice to a character troubled by diverse emotions and societal expectations—say, the acknowledgement of the necessity of his wife going out for work in the age of economic crisis, and at the same time the burden of guilt that his masculine identity carries for this ‘dependence’; the pain of the wounded self because of the loss of job as his bank crashes adding to a typical male-centric fear of losing control over his working wife, and his sense of insignificance in the presence of his father’s old ‘successful’ students ( those doctors and barristers his tormented father used to visit for some financial help with a belief that as a teacher he has got some ‘claim’ over them). Chatterjee’s subtle acting, his body language, his silence and above all the movement of his eyes—Ray taps the creative energy of this talented actor.

However, Ray sees hope amidst the crisis: the recovery of love at the moment of turmoil. Arati has resigned. Her husband has lost the job. But then, in that nothingness they find everything—the intensity of their bond, the power of love. They find themselves. There is no more any broken communication. Love heals. Yes, the camera depicts the big city, its offices, banks and corporations, and its flow of people. The struggle goes on. Amidst this struggle in the city, they rediscover the power of love; they realize that they constitute an indivisible whole, and together they would fight and survive.

Does this union of the masculine and the feminine show us a new path in our times characterized by acute loneliness amidst the rhetoric of liberation?

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.