FILM REVIEW

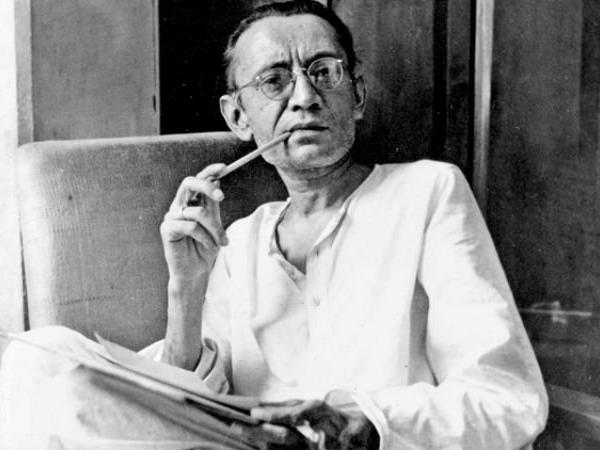

Nandita Das’s directorial project Manto is a nuanced and intricate tale of the complex mind of the writer known for his radical commentary and sarcastic sense of humour.

Rajeshwari T / The New Leam.

The anguish of a writer is difficult art to capture, for within this anguish, lies the anguish of the entire civilization. For an elusive writer like Saadat Hasan Manto, the task to capture it takes tremendous challenging leaps. Nandita Das’s Manto makes a brave leap in that direction.

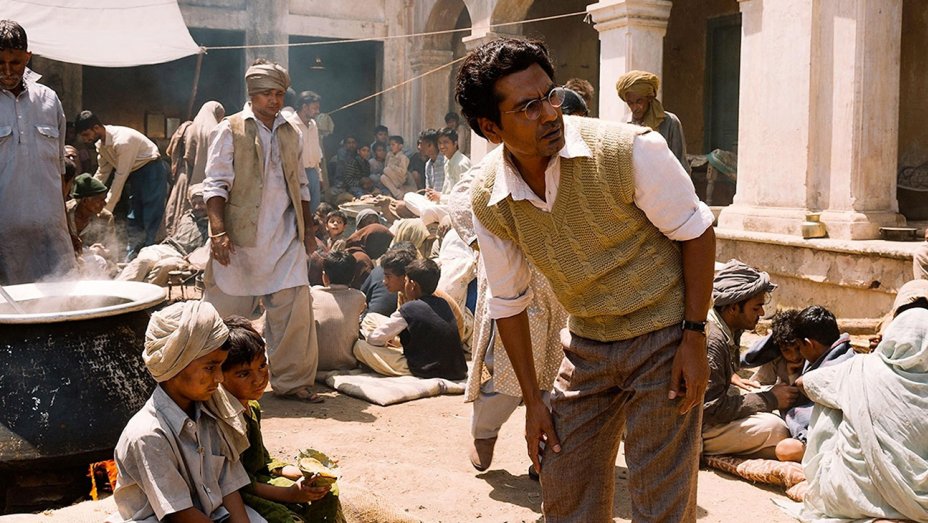

Manto (2018) is a movie based on the life and times of the maverick writer and is directed by Nandita Das and stars Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the lead role. The movie aims to capture the eventful life of the writer set during the immediate years before and after partition, and weaves within it the intricate tales of rising religious intolerance, an artist’s struggle for freedom of expression, angst of getting uprooted from the place of belonging, and the struggle of an individual within the larger crushing forces of the societal norms.

The movie begins with the dramatization of one of his earlier stories set in Bombay in the 1940s, Dus Rupay. The story starts with a girl in her early teens accompanying older men for a picnic. The girl’s innocent excitement to take a ride in the car, the preying eyes of the men, ends with a twist from which the 15-year-old Sarita breaks out without being a victim. The narrative of Dus Rupay seems a fitting prelude to begin the story of a writer whose positioning of female protagonists in his stories serves as a channel to confront his own humanism.

Nandita Das’s Manto glides and churns Manto’s fictional stories by portraying his own present. The characters spring to life as Manto searches for them with his resolute eyes as he walks through the squabbles in Bombay’s streets, the glamorous parties he attends, within the rubble of death and destruction that partition lays in front of him.

The chilling stories of Thanda Ghosht, Tobak Tek Singh, Khol do, and Sau Watt ka Bulb come alive and stare into the eyes of viewers within the compelling circumstances in which they were conceived by the writer. The cinematic device of Das by engaging the viewer with the writer and his creation simultaneously humanizes the writer and his story and allows one to embed the story within the historical contexts from which they emerged. Through the narrative, the movie allows the viewers to engage deeply with the questions, where and whom did Manto belong to? What are the costs that artists are compelled to pay to retain their truthfulness to their art? The centrality of rootlessness and restlessness in Manto’s life and its reflection in his characters and their stories.

The movie also at its centre poses the conflict Manto faces while confronting his Muslim identity during the troubled times of Partition.

Manto, a non-practicing Muslim, who has critiqued religion through his wry humour and sharp wit, faces the sudden vulnerability of confronting his religious identity. This vulnerability uproots him from his beloved city, Bombay, and within this anguish of being uprooted, Manto’s life furthur evolves and dissolves in front of the viewer through his tenuous relationship with the Progressive Writer’s Association, his poverty and alcoholism in Lahore, obscenity charges imposed on him, and his deteriorating state of health and his years in asylum. Nandita Das offers a rich detail to the viewer by bringing to life the role of a closed circle of people who played an influential role in the life of the writer- be it enquiring eyes within large framed glasses of his wife Safiya (Dugal), effervescent Shyam Chaddha (Bhasin) and his deep bond with Manto, his friendship with Ismat Chugtai ( Deshpande ) among other contemporaries. In the backdrop of gloom and pregnant tension of partition, these characters gleam as torches through their struggles, questions, and their rich literary contribution to humanize the apathetic human conditions.

While Das’s Manto does bring the layered and nuanced life of Manto to the screen, within its respect for the characters, it offers a soft edge to the other attributes of Manto’s life- his billowing rage, his sharp wit, his lonely defiance, the workings of his conflicted personality in relation to the times of setting up of the two nations, and his differences with other writers from the Progressive Writer’s Association.

The court scene in the movie, while highlighting the lonely fight of an artist against a stifling moral order which is unable to distinguish vulgarity from the freedom of expression, falls short to land its blows within the confines of Manto’s elusive personality. Perhaps, for a writer like Manto who slips in and out of the fictional work he creates, it is hard to sketch a defined portrait and capture him within one lens.

While the film itself is built within the solid historical foundation of partition, the questions it raises on the freedom of expression, of the apathetic conditions of living conditions, the anguish of a writer of acting as the mirror to a society and the burden it brings, and the frail identity of the individual and its vulnerabilities in the times of polarization in the society, scream as a plea to acknowledge the current state of affairs in the nation.

While Nandita Das’s Manto will boggle a viewer, who is unaware of the life and times of the writer, it does speak to the viewer of larger questions of retaining our humanity within tough times that lie in front of us and recognize our own alienation from the world that stifles our conflicts and paralyses us by individualizing us on grounds of differential identity.