Sarah Pitt, Principal Lecturer, Microbiology and Biomedical Science Practice, University of Brighton

There’s been a surge in measles cases across Europe, putting people’s lives at risk according to new findings from the World Health Organization.

The official figures show that approximately 90,000 cases have been reported for the first half of 2019. This is already more than the number of cases recorded for the whole of 2018 (84,462).

This has in part been put down to disinformation about the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine on social media putting parents off vaccinating their children.

Recent outbreaks of measles, which is much more infectious than mumps and rubella, have been widely reported. But what is less well known is that there have been a few babies born with congenital rubella syndrome in the UK in the past few years. This is an illness resulting from an infection of the rubella virus during pregnancy.

Rubella babies

People under the age of 50 are unlikely to have heard about “Rubella babies”, but in the 1940s, the Australian paediatric ophthalmologist, Norman Gregg, made the connection between women being infected with German measles (rubella) during pregnancy and their children being born deaf and blind and sometimes with other disabilities.

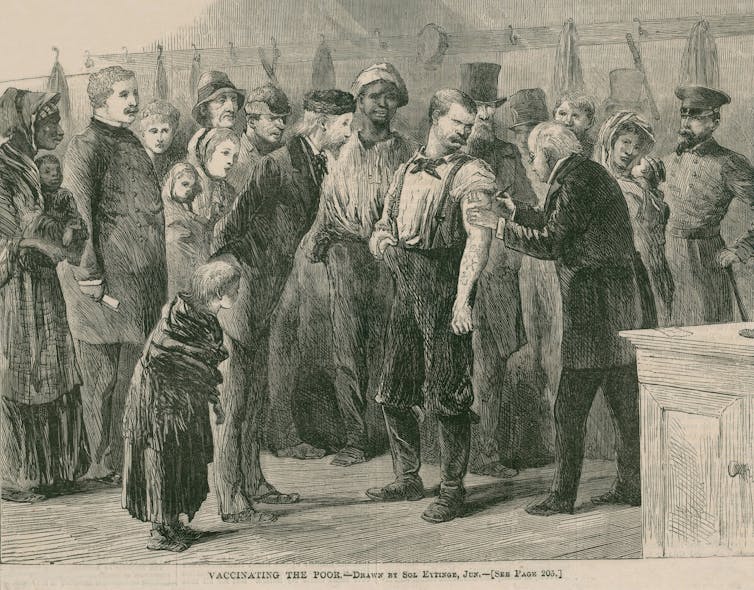

Many babies infected with the virus while in the womb do not survive, but in the 1960s in the UK about 300 children each year were born with “congenital rubella syndrome” and needed care. By 1970, a safe effective Rubella vaccine was available and the UK began vaccinating school girls. A screening programme, which involved testing blood samples from women of childbearing age to see whether they had previous immunity to the virus, also began. Those who did not did not have protection were offered the vaccine.

OneSideProFoto/Shutterstock

Although women starting in particular jobs – such as health care and teaching – were screened, most of the tests were done on pregnant women as part of their 12 week check. In 1988, the Rubella vaccine become the R in the MMR and the strategy changed to vaccinating all pre-school children.

The idea was that if all young children were protected, then these infections would eventually not be circulating at all. During 2016 and 2017, routine screening for Rubella antibodies during pregnancy was phased out across the UK. It was considered not cost-effective, since Rubella infection during pregnancy was extremely rare and most people in the UK of child bearing age should have received MMR as children. But the recent outbreaks of measles across the world have illustrated the problems with MMR uptake.

Misinformation and memory

Why are people reluctant to have screening tests and vaccinations to prevent diseases? While some of the reasons may include loss of trust in “experts” and people in authority, I wonder if it is also partly because the stories of such diseases have been long forgotten.

When Eva Peron, the First Lady of Argentina, died from cervical cancer at the age of 33 in 1952, for example, early diagnosis was not possible – and chemotherapy treatment was in its infancy. So for women who developed this disease, a distressing illness and painful death were more or less inevitable.

The design of a laboratory method for detecting early changes in the appearance of cells in the cervical region – the “Pap smear” – eventually made regular mass screening possible. Since the introduction of the scheme into the UK in 1988, it has prevented thousands of premature deaths in women each year.

Everett Historical/Shutterstock

The discovery that most but, crucially, not all cases of cervical cancer are attributable to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection led to the development of the HPV vaccine which is now given routinely to teenage girls – and in some countries boys as well. Evidence from the UK programme, which began in 2009, suggests the vaccine is very effective and this should help to further reduce the number of women with cervical cancer among the under 30s.

Yet despite all that’s known about cervical cancer and the importance of going for a regular smear test, many women still appear to be reluctant to go. It’s estimated that about three million women across England have not had a smear test for at least three-and-a-half years.

In the 20th-century, there were major advances in disease prevention, which improved both life expectancy and quality of life. But it seems these health and societal developments are now being overlooked. Indeed, giving people information and instructions is no longer working. So perhaps it’s time to appeal to people’s hearts by telling the stories of these diseases – and how they have affected real people.

Gruesome photos on cigarette packages, for example, massively help to reduce tobacco use, so maybe something similar now needs to happen in terms of vaccinations to tackle the latest epidemic and anti-vaxxer campaigns around the world.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.