Recently we have witnessed an intense debate on the proposal for introducing ten per cent reservation in educational institutions and government jobs for the poor belonging to the forward castes across religious faiths. In this context there are five key issues that deserve special attention.

Firstly, we need to see the genesis of the policy of reservation. We live in an intensely stratified, hierarchical and unequal society. Caste, class and gender- these three locations of one’s social position have often shaped one’s life trajectory and destiny. The routes of this hierarchy could be seen in some of our dharmashastras and also exclusionary social practices that retained a largely casteist and patriarchal social order with uneven distribution of cultural, social and economic capital across class, caste and gender. In the process of the nationalist movement, the debate on social equality through the discourses of Gandhi, Ambdekar and Nehru occupied a major space. In a way it did effect the agenda of the post-colonial Indian state. Not surprisingly after independence we introduced the scheme of reservation or protective discrimination for the marginalised castes. Its essential idea emerged from the conviction that the doctrine of constitutional equality could not be practiced in a vacuum; there can be no equality between say a reasonably wealthy forward caste male and a poor Dalit person belonging to a family deprived of the light of modern education since ages. To give a real thrust to the egalitarian aspirations of the new republic, reservation was seen as one of the ways to eradicate socio-economic inequality and create a culture of fraternity.

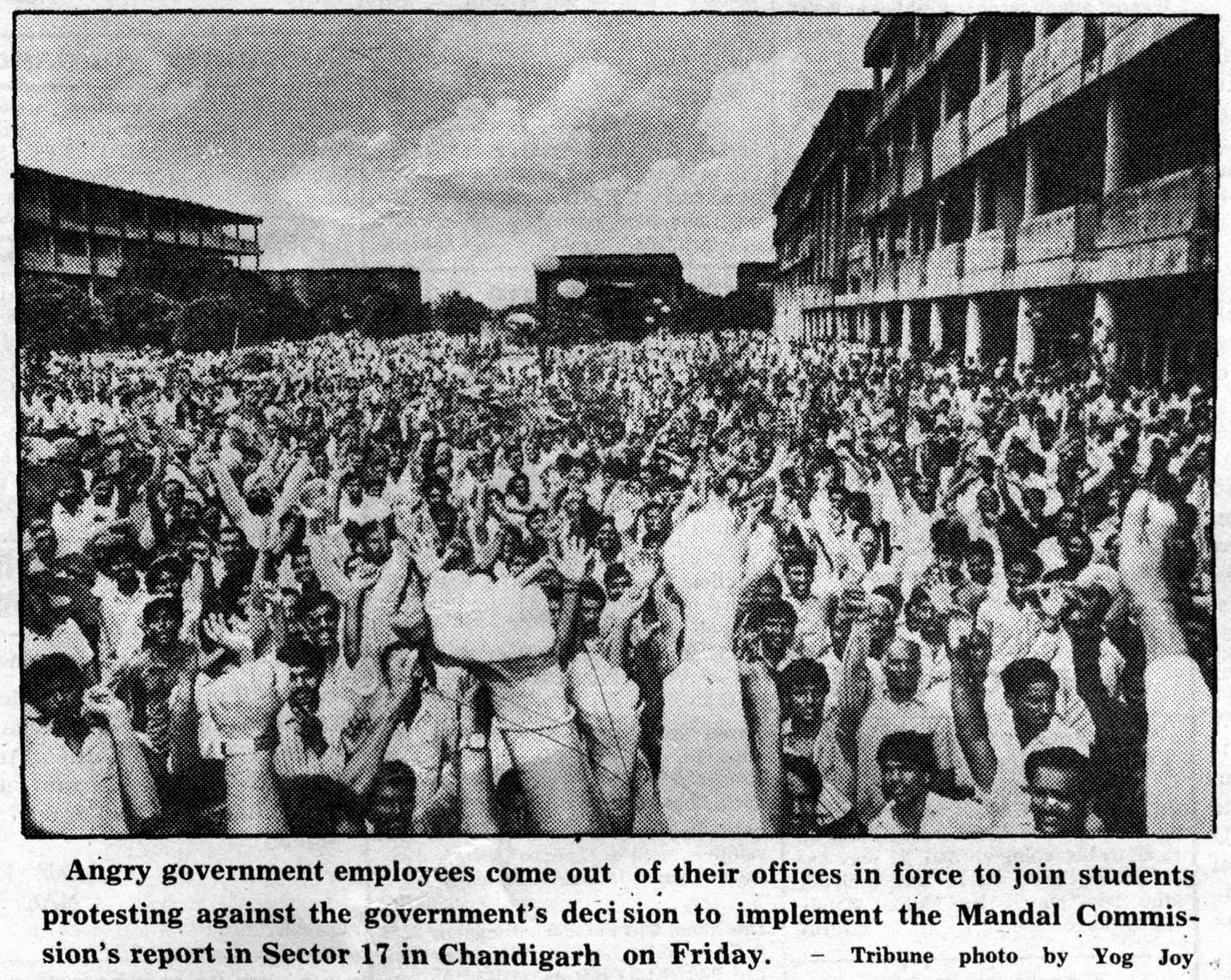

Secondly, while these early objects behind reservation were noble what eventually happened in subsequent years was the rapid political Machiavellianism centred on the passion and emotions relating to social justice and discrimination. Each political party depending on its constituency began to demand more and more reservation. With the growth of assertive identity politics the scope of reservation began to widen itself. Its culmination was the implementation of the Mandal Commission Report(1990)by the then V.P. Singh government. With the reservation with the other backward classes the nation also witnessed a politico-cultural turmoil. There was anti-reservation protest launched by the students belonging to the forward castes and caste based social identities far from withering away began to become more and more visible.

Thirdly, it is important to see that reservation alone cannot be the entire substance of social justice . Reservation can prove to be enabling only when as a nation we are sincere in eradicating the roots of hierarchy and inequality through economic measures like land reform, redistribution of wealth, creating job opportunities, minimum wage schemes, developing rural economy and agrarian sector and also generating a sustained socio-cultural movement for bringing about a new consciousness that teaches us to look at one another as human beyond the limiting parameters of caste, ethnicity, gender and religion. It is really tragic that the political class loves to engage in the rhetoric of reservation and social justice and mass stimulation of identities without bothering to work substantially on political economy, distributive justice and social reform. As a result we found ourselves caught into the trap of reservation. Today, ironically it is becoming difficult for us to take the debate on social justice beyond reservation.

Fourthly, in an overpopulated country like ours with uneven economic development, a sense of scarcity and chronic anxiety for livelihood- the people are continually haunted and even not so economically privileged sections of people among the forward castes bear the brunt of this crisis. This has created a psychic milieu conducive to the recurrence of caste consciousness and associated stigmatisation. While the forward castes, because of their own career anxieties in an economy of scarcity begin to stigmatise those who as they think are getting the benefits because of reservation, the Dalits and the lower castes continue to see forward castes as equally oppressive, exclusionary and hierarchical. Relationships become a casualty and despite years of independence, caste consciousness finds its roots stronger in India.

And fifthly, at this moment in this election year when we saw such hurry for implementing this new reservation bill, there are indeed reasons to be worried about. Is it a genuine, integrated attempt for creating a socio-political environment conducive to economic equality, fraternity and social justice or is it yet another strategic game about numbers for targeting the potential vote bank and further stimulate caste identity in a society that has yet to embrace the gospel of what B.R. Ambedkar regarded as ‘Liberty, Fraternity, Equality.’