When we use the word today, however, it is much more linked to individualism—a semantic shift of no mean proportions. We speak of individual human rights, including, in America, the right to bear arms; the right, in a democracy, to vote, etc. Often contrasted with the collective, and set off against the brutalities of totalitarianism, it has become the common badge of freedom. Because of these relative advantages—women’s rights, not woman’s suppression—we tend to ignore the limitations imposed on our consciousness by what is, essentially, political thinking.

As things exist today, we start with fragmentation, of which the nation state is a prime example. Divided off into “peoples”, with different languages and cultures, we attempt to put the pieces back together through organs such as the United Nations. These, again, may have some advantages, but they are inevitably limited and, often, short-lived. Our attempts to deal with problems piecemeal—and, indeed, to construe them in the first place as problems—indicates that we are dealing with them fragmentarily. And, as we well know from experience, each solution contains and calls forth further problems. There is no end to it, at the level of thought.

Is it possible, then—the question begs itself—to begin, in some sense, with or from the whole? The question is tricky because thought itself is fragmented: as the nation state, so is the individual. But, though it may seem a contradiction, some approaches are more “whole” than others. Why not start, for instance, with Planet Earth as a whole?—this beautiful, blue, floating ball which we can now all see as if from space. It is, after all, our home, whether we live in Africa or Australia. What prevents us from seeing this “global fact”, especially now that it is there before us, if not our commitment to our own nation/ tribe? We can, and we should, study the facts— overpopulation, air and water pollution, the loss of species, environmental degradation—and begin to see that we are responsible: it is human beings who have brought this about. This is not some kind of “guilt trip”, but a simple acknowledgement of facts. And, with goodwill and co-operation, what has been done can be undone. The fact itself is a stimulus.

While the cosmic order may be something that one feels on a clear, starlit night when everything is still, it lies within our grasp on a daily basis to bring holism into the curriculum. This means that we begin with the whole and not the part, with the human being, not the Easterner or Westerner. The Earth is our home; it is also one—one integral system, sometimes called Gaia. All is a net, a web of relationships, which we acknowledge when we speak of the World Wide Web. But, not merely an information network, it is the source and basis of our being-in-the-world, as indispensable as the air we breathe. We cannot take a step without it, literally.

What is it, then, that has divided us? The route leads back to consciousness. It is in the nature of consciousness as we know it to break things down, to analyse, to fragment—and from there to construct, as one might build a bridge. At the physical level, it works very well; without it we would have no technology, no medicine, no science, no instruments, no culture. But at the level of our being, at the level of who we are, this process of division and separation is deadly: it divides the East from the West, the Black from the White, the Arab from the Jew, etc. It is the cause of class consciousness, sexual violence, psychological conflict and, ultimately, war. It also enhances at every step the sense of oneself as a separate individual. And, when this separation becomes too intense, there is nervous breakdown and psychological collapse.

The fault seems to be that we accept without question the status quo of this consciousness. We may examine the detail—we do in therapy, for instance—but we take it for granted that “this is it”: the consciousness we come with is all there is. In this way we ensure that nothing much will change, that the most we can hope for is improvement, reform. To speak of revolution is a kind of heresy, the brain child of “marginals” with nowhere to go. But, to start with holism and the whole human being is in itself a kind of revolution; it is the beginning of something whose future is unknown. For, the ordering of thought is completely predictable and that is one reason we cling to it: it gives one a sense of complete security, however illusory that security may be. If, for instance, I espouse a religion that prosecutes war as a means of making peace, I may be utterly certain of the rightness of my cause, whatever the consequence to others. It is the affirmation of the consciousness of mankind, which has evolved superficially over time but which has remained what it is: ignorant and barbaric. To bring about a mutation in this consciousness is the goal of holism and of all true education.

What does it mean to care for the whole, to care for the land and for other human beings? In the first place, it means that I do them no harm, that I think of them as integrally linked to myself. It also means that I must “start near”, with my local landscape, my own backyard; with my wife, my family, the people living near me. For, in this relationship lies the seed of whatever may grow in terms of the world, that is, the natural and the human environment. It is not a matter of a grand design, some blueprint for the planet or the brotherhood of man, but of developing a sense of deep connection, the endemic feeling that whatever I do—indeed, whatever I think and feel—is affecting the atmosphere we all live in and is therefore contributing to its value or its loss. This demands an act of complete attention, an awareness of everything in me and around me. For, indeed, in a deeper sense the world is me.

We have been trained to be positively self-assertive, in the name of our nation, our religion, our class. As an attitude of mind, it is this self-assertiveness that is the bedrock of individualism. The self, the ego, is the real enemy. It is not enough, however, to acknowledge its existence or to identify it as the root of the problem. We need a new and different way of thinking—what Krishnamurti calls negative thinking—to begin to unravel its intricate complexities. Positive thinking fixes and asserts: it establishes procedures, writes laws, builds dogma; ultimately, it is the backbone of the “me”. Negative thinking, on the other hand, has no fixed point or purpose in mind: it is fluid, non-assertive and does not within its field create an object which then becomes its focus. It is still in movement but without the attachment which is the very pith, the core, of the ego.

Negative thinking is a vital clue to the necessary work of unravelling. It loosens the mind from its inveterate tendency to fix on something and to live/ move from there. Once the mind thus sees its own operation—the mind seeing itself, as it were—it is liberated, at least to some extent, to look at itself as a whole operation, that is, non-fragmentarily. With the curtain of the self drawn back for a moment, we can begin to contemplate the open stage of observation without the observer, a looking and a seeing without distortion which is in itself the beginning of intelligence.

We do not realise, most of us, how distorted our view of reality is. It is not merely a matter ofprejudiced opinion—the inevitable colouring of “my tribe”—but, at a deeper and more significant level, the very process of consciousness itself. We know the old-colonial divide and rule, but do we see it within ourselves—the way one fragment dominates others, the aggressor and the victim—the war within ourselves? Are we aware of our own conflicted nature? When things are running smoothly we may not be; but let there be a crisis, a sudden demand, and we quickly discover how ill-prepared we are, how much we soft-pedal our way through life.

This is where, and why, we need an approach that begins with the whole and not the part—with attention and awareness, not analysis and thought. Krishnamurti sometimes alluded to this as “starting from the other shore”. One does not have to be enlightened to do it, which is the assertion of a sterile mind. It is enough to see the curve of a road, the contour of a cloud, the movement of a leaf. Just to see it without adding to it, without saying it is ugly, it is beautiful, whatever. It is tantamount to shifting the seat of our learning from the reflective/ thought-centred to the observational/ seeing mode. For in so seeing, not operating on, we dissolve the distance between ourselves and the object; we begin to break down within ourselves the fatal division between myself and the world, that is to say, consciousness as essence (cogito, ergo sum) and the world as an independently-functioning machine. That this division is false has been amply demonstrated by the extraordinary findings of quantum physics where the presence, or absence, of the observer has a crucial impact on the behaviour of particles.

Somehow, however, this discovery has not yet found purchase in the realm of the psyche. Is it because we are, at bottom, convinced that we are individuals? We are unready, or unwilling, to take the next step. Even if we see that the world is in crisis, and are perhaps active in one sphere or another, we cannot—or we do not—make the link between the world without and the world within: it is our own selfishness, ultimately, that is the cause of suffering both within and without. And without seeing that fact, we can, at best, bring about piecemeal solutions, ameliorate but not heal. The solution to our problems lies within ourselves, and it is only by going to the source, within ourselves, that we can come upon an action that is whole, true and meaningful. We need a different tool from the worn-out tool of thought—something much quicker, more compassionate, more incisive; something that speaks to the immediate moment in a way that thought, however sharp, cannot. Using Krishnamurti’s language, we may call this tool intelligence. This intelligence has no pre-scripted agenda: it is the active component of awareness/ observation, knowing what to do by being fully present. In this sense of “full presence”, it is also free of time, which releases action from the trammels of conditioning. For conditioning is in itself thought-time, and within its grasp there can be no freedom. When we begin to see this fact for ourselves, we are already setting forth, already breathing in the fresh, clean air of the self-generating Whole. The journey that has no ending has begun.

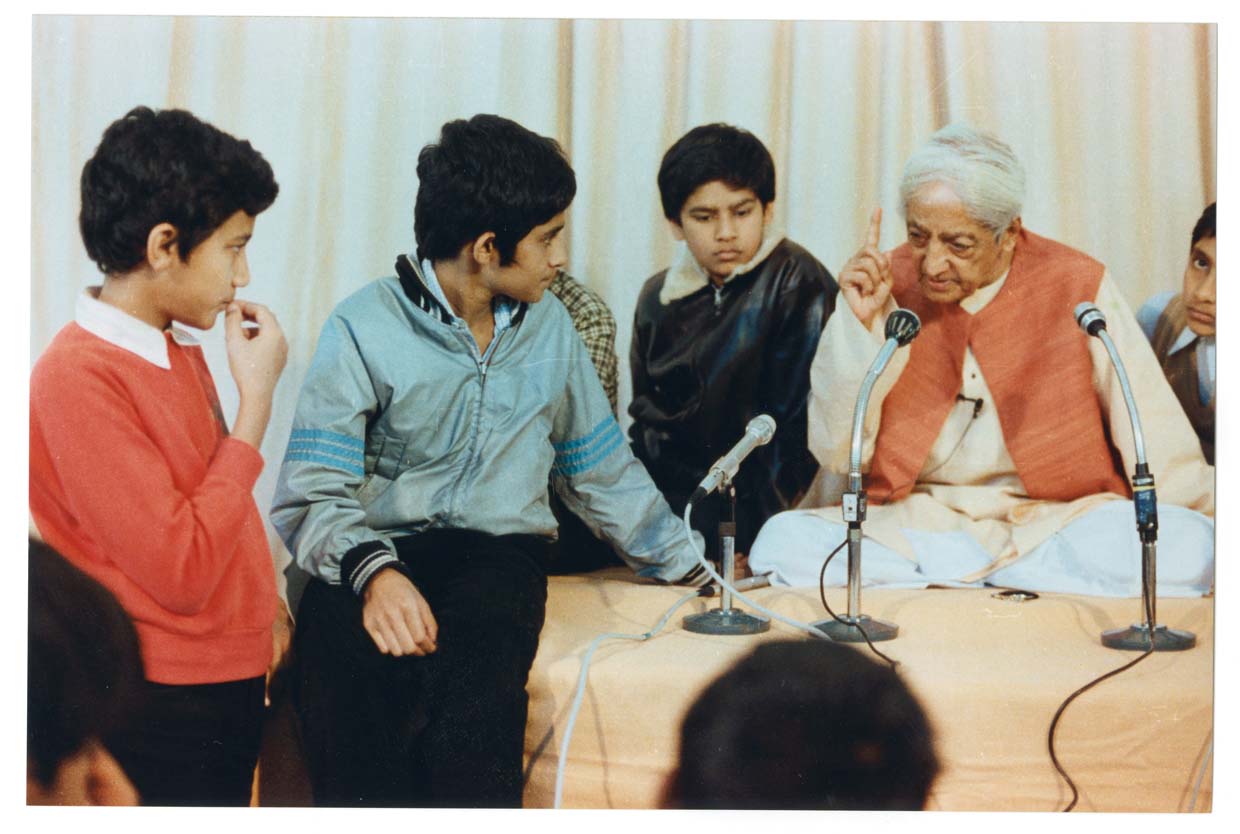

Stephen Smith was the Acting Principal/ Academic Director, and a teacher at the Krishnamurti Brockwood Park School in England with twenty years of experience in the field. While living in Ojai, California, he was the Centre Coordinator for the Krishnamurti Foundation of America, organising events and facilitating dialogues. He now divides his time between his home in England, Ojai California, and various places in India where he continues to give talks and facilitate dialogues.