It was on the fateful day of January 30,1949 that Gandhi was killed. Seventy-five years have passed by and we seem to have reduced the days marking his birth and death anniversaries into mere state sponsored rituals ranging from homages by eminent personalities, inauguration of village industries and routine lectures and seminars on themes surrounding non-violence, truth or gram swaraj. In the intellectual circuits Gandhi continues to excite sensibilities and his ideas are often juxtaposed with prominent others like B.R. Ambedkar around the question of caste, Bhagat Singh whose execution he supposedly did not do enough to stop and Shubhash Chandra Bose valorised as a Bengali icon who Gandhi did not appreciate enough or refused to share the limelight of the nationalist struggle with. In the last couple of years, Gandhi’s version of Hinduism is seen to be diluted against the backdrop of a puritan militant Hindutva dominating the present air of politics today. Controversies, sensationalism, allegations and rebuke are as much a part of the thinking about Gandhi as is the culture of seriously engaging with his mindscape which for many sparks genuine interest and inquiry.

Amid all these social, political and intellectual engagements with the man and his thoughts, educationists and practitioners in the field often engage with his ideas and explore how some of them could be experimented with in real classroom settings. Can Gandhi’s grand landscape be reduced into a couple of references in history textbooks or can random quotations from his works/speeches be enough to understand the complexity of his world view or can Gandhi be reduced into a disciplinarian, puritan-sage who was too harsh on himself and abided by principles too impractical for this world? It is paradoxical that an exhaustive, vibrant and life-affirming engagement with Gandhi’s ideas is missing despite the fact that his relevance is unprecedented as we are conflicted with multiple challenges ranging from communalism, intolerance and inequality to environmental crisis and destruction of nature. Within this scenario, how can we help our children engage with Gandhi and walk with the ideas that he stood for?

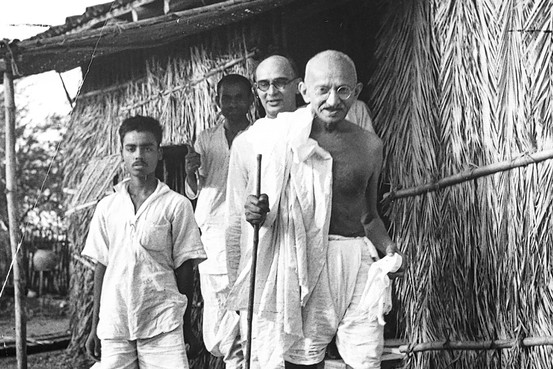

Gandhi was not a scholar, university professor or a mainstream/conventional statesman. Gandhi never refrained from exposing his vulnerabilities or being frank to admit his mistakes and weaknesses and thereby made himself available to criticism. Engaged and reflexive pedagogy that builds on Gandhi’s perspectives and adapts it to the need of the contemporary classroom is what we truly need today. Through engaged pedagogy in the classroom a space could be created where young learners feel excited to explore Gandhi’s life and ideas and it is with this intention that we conducted a couple of experiments in very humble, ordinary and even deprived classrooms in India’s rural hinterland.

Let’s drink from the same glass and eat from the same plate

Rural India is infected with caste consciousness and it presents itself as an overarching reality impacting almost all aspects of life whether it is daily interaction, parameters of association among people, division of labour and associated social status and access to even basic opportunities such as dignified housing, clean drinking water or even educational prospects. Most Indian villages compose of segregated habitats for different caste groups, the marginal castes most often occupying the fringe or extreme outer parts often deficient in basic facilities otherwise available to the more affluent upper caste parts of the village. Working within such groups one walks with Gandhi and Ambedkar simultaneously.One sees how children from the Dalit/marginalised caste groups lack a sense of self worth, confidence due to generational histories of being rebuked, overlooked and ignored. They only develop a trust with enough time and their parents stop seeing you with doubt after you have stablished your intentions beyond tokenism and superficiality. You realise that in all efforts to generate trust you must hold hands with both Gandhi and Ambedkar. Your critic of caste must be strongly articulated and all practices associated with it must be fought against without a minute’s compromise but at the same time you must cultivate the patience and far sightedness of Gandhi. This will help you transform the mindset of the community in the long term, even if this process seems long-term, aspirational and promising slow results. Caste after all is abolished in the legal framework of our country but surely it has not vanished from our deep rooted consciousness, this reminds us that the enemy within must be fought from within and we must not satisfy ourselves merely by the onslaught of the exterior enemy. We shared food and water in our engagements with children in Bihar’s villages and the only condition we put before participants was that they must leave their caste, ego and shoes at the door and that in our time together, we will all be seen as equals with a shared sense of dignity and wellbeing that we would all fight to preserve at all costs. This was a first of its kind experiment for many of the participants as they had never imagined drinking from the same water bottle or sharing lunch boxes with participants from the other extreme end of the spectrum. These gave us occasions to talk freely, chat, laugh and crack jokes and eventually break years of inhibition and cold war like unsaid tensions between us. Of course it took time but what we realised was that something as simple as sharing a meal can be an effective way of conflict resolution. Yes, Gandhi and Ambedkar also accompanied us over delightful conversations as we sat together to enjoy a meal! On an everyday basis we would clean the classroom premises in sessions we called ‘shramdan’. Here all the children and the teachers had to clean up the school campus collectively and nobody could say that they would only clean the library and make posters and others (from specific castes)would clean the toilet or mop the floor. Yes, initially the way boys and girls, upper caste and lower caste children divided work among themselves was problematic but with regular sessions where honest conversations, deep seated social values and prejudices were openly shared, they all gradually agreed that something was not quite right and needed to change. Shramdan became that agent of change and of hope in many senses.

Cleaning the toilet, cleaning the ‘dirt’ in our consciousness

Can a teacher, advocate, doctor, engineer or businessman clean a toilet? In a caste ridden society like ours tasks like cleaning the toilet are often looked down upon and seen as a somewhat polluted and unfit for the educated, privileged or upper castes. It is not enough to theoretically fight the bondage of caste without actually challenging it in real life situations. Taking inspiration from Gandhi when he engaged in a dialogue with his wife Kasturba on why they should be cleaning their own toilets and not think that it is polluted task fit only for a certain caste group, we invited all the teachers to join hands in cleaning up the toilets in our premises. Shocked and taken aback, many of them did display a sense of discomfort. But dialogues, open ended discussions and even debates paved way for at least rethinking the issue and challenging conventional ideas and practices.

With engaging discussions on caste and everyday life, reading passages from Onprakash Valmikis’s Sadgati, an awareness of our fundamental

rights- I saw a small revolution unfolding itself. Children coming from privileged castes started woking together with those from the lower castes, whether it was moping, sweeping or toilet cleaning. I saw Dalit children taking charge of the library and using the computer. The culture of collective labour was taking place, together they were bringing change. They too were debating with parents and generating awareness. Now the classroom was vibrant.Here they had just one identity, and that was of a learner, a seeker. The pedagogical experiment was successful.

Education as a weapon against exploitation

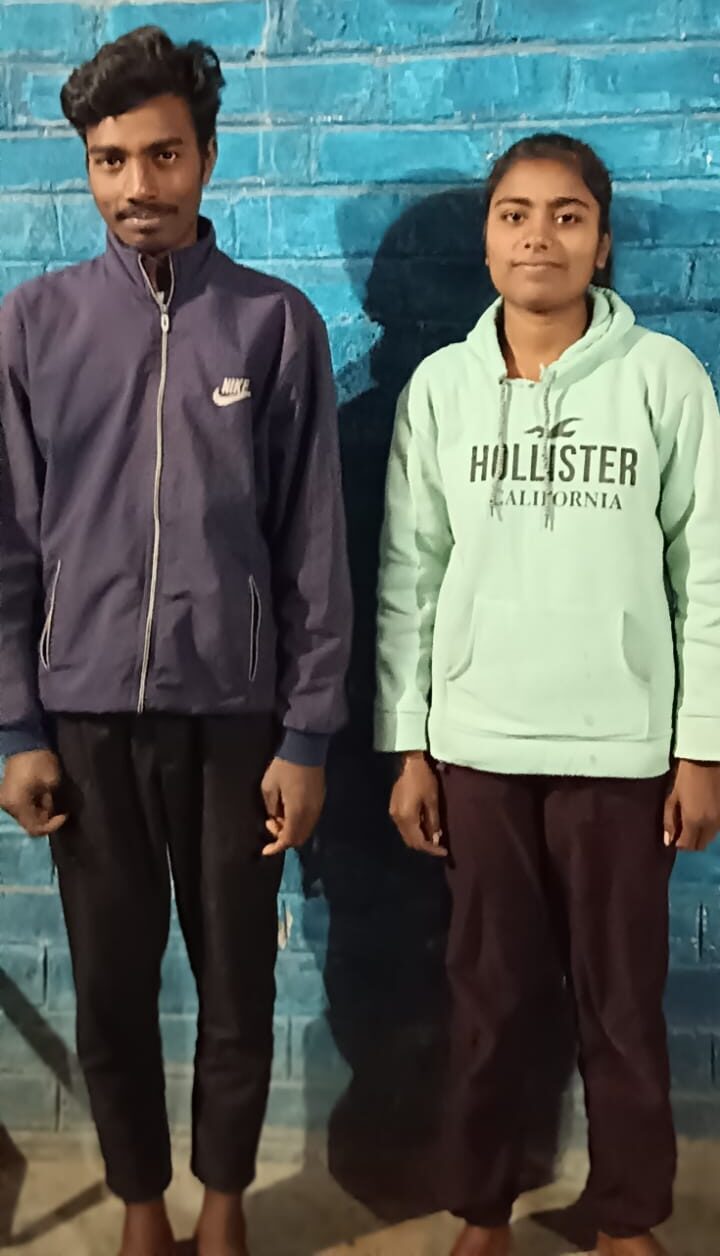

This is the story of Chanda, 14, and Sanjeev, 12, who are siblings and belong to one of the most disadvantaged communities in the village. Their parents are seasonal agricultural labourers and they are both first generation learners. The family income is extremely low and the family lives under several small and medium sized debts taken to meet the essential survival needs. Recently, their father was arrested by the police for having consumed alcohol in the legally dry state of Bihar. He was dragged to the police station and was in the lock up for a few days in which the family faced extreme harassment, rude behaviour of the authorities and a sense of being left out. The children, being exposed to a new sense of confidence owing to their education asked the police for a copy of the FIR. They knew it was their right to have access to this report. With help from well-wishers, concreted elders of the village they eventually were able to have their father released. The paper work and the associated running around was done by the both of them and they bought their father back home.

They experimented with the power of education for the very first time. The importance of literacy was accepted by the whole community who appreciated the alertness of the siblings. Their father was proud but ashamed too, he knew that his children had undertaken so much difficulty to release him. He stoped consuming alcohol. These experiments show how engaged, empathetic and dialogic pedagogy can take us beyond the confines of the classroom or the limitations of textbooks. In fact, they can be life transforming.

Through engaged pedagogy and a belief that change is possible, the classroom could excel far beyond our imagination. Gandhi’s relevance in our classrooms is certainly undoubted and we can experiment with his ideas to generate newer possibilities in the classrooms and beyond.