In this remarkably sensitive piece the author has reflected on the meaning of his journey towards a Himalayan village, his relationship with the vitality of the city, and his existential quest.

Avijit Pathak is Professsor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.

I live in a city. There was a time when Kolkata fascinated me. Yes, it was my first city—my remarkable journey from a small town to a huge city. I was young—a college student. Kolkata became my addiction. Its bookshops and coffee house, its theatre and cinema, its political vibrancy and its immense vitality—everything aroused my imagination, opened the windows of my mind, and enabled me to see and experience life with all its thrill, mobility and performance. From Kolkata to Delhi—there was yet another journey. The capital of the country further enriched me. Its vibrant university culture, its multiculturalism, its historic memories and its continual growth and development made me feel the meaning of living in a city—its speed and mobility, its utility and economic possibilities. In a way, these two cities gave me the taste of modernity: the process of individuation, achievement-orientation, social mobility and cultural experimentation.

Moreover, I got my livelihood and vocation in the city. I found people of my kind—students and young learners, teachers and intellectuals; I found theatre, cinema and music. With good schools, good colleges international conferences and seminars, mega hospitals, flyovers, expressways, market complexes, metro railways and airports—the city aroused a notion of ‘good living’ and ‘security’. Jobs are here; newspapers and television channels are here; doctors are here; new opportunities are here, political decision-making is here. It is difficult to believe that one who has got the taste of a city can think of any other mode of living.

Yet, life is never straight forward and unilinear. Even though I continue to live in a city, I hear yet another call. Possibly, something is happening inside me. For instance, I ask myself: Is it that God has given me a pair of eyes only to see the traffic light, the movement of the vehicles, the glitz of the malls, the imageries in the mobile/computer screen, the billboards, and the cage like flats and apartments in the gigantic towers? Or is it that my ears exist only to receive the noise of television channels, loud music, the horn of cars, buses and local trains? Do I exist only to be a prisoner of time—measuring it, fragmenting it into hours, minutes, seconds, and using it for ‘productivity’ and ‘efficiency’?

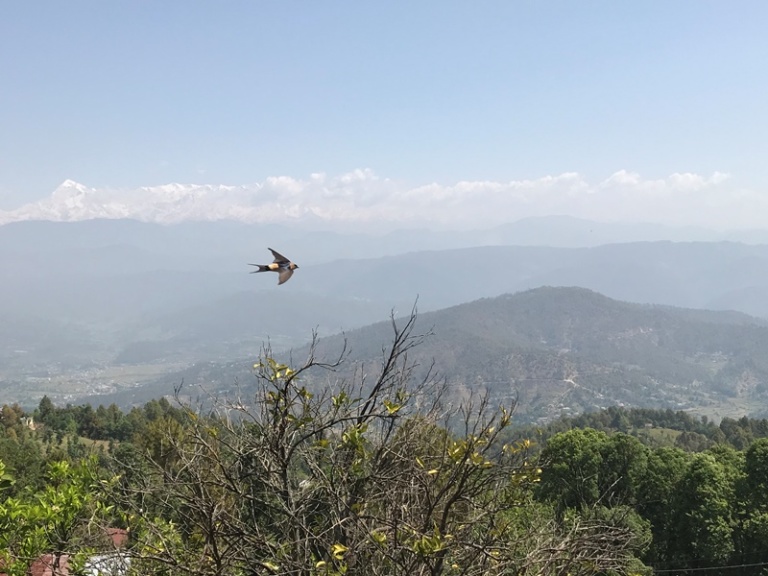

At this juncture, I enter a domain of ambiguity. The pragmatism of city life or its utility fails to satisfy me fully. I begin to strive for something else. My eyes want to see the vastness of the sky, the snow clad mountains, the colourful butterflies roaming around; my ears want to receive the whisper of pine and oak trees, the music of silence in a rhythmic walk through the curved roads of the hills; and my existence needs the experience of surrender—not conquering the world with a sense of being a ‘proud doer’, not rushing for reckless achievement, but living in the moment and experiencing the joy of ‘idleness’, and allowing the mystery of the next moment to envelop my being. It is at this juncture that I come to a Himalayan village.

Well, I used to come to this village in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhad, and then my identity was that of a tourist. I used to come, stay for three/four days in a guest house, move around, and then leave. Naturally, for the villagers, I was a city dweller—possibly a sensitive tourist striving for a change from the busy life of the city. Beyond that they would not show much interest in me— the interiority of my personal life. But then, as I become more serious about my plan to stay in the village for a longer time, and plan to rent a house within the village, things begin to take a turn. This turn is interesting and existentially puzzling for many reasons.

First, I see the power of the local village community as enabling as well as constraining. It is enabling because unlike the heightened anonymity that exists in the city space, here are people who acknowledge your presence; they smile; they talk; they relate more easily and comfortably. In a way, unlike sophisticated city dwellers they have no armour. However, at times, it is constraining. They would ask you all sorts of questions: Why do you want to stay here? What is your daughter doing? What is her age? When will she get married? Their eagerness to enter my inner world is somewhat perplexing. One reason is that in the city we are used to something else—indifference to others. Well, at times, this indifference or non-interference enables you to live as you wish. I keep asking: Which is better—utter indifference or undue interest? Is it possible to find something else—neither the anonymity of the city nor the communitarian invasion in one’s private life, but genuine art of relatedness with one’s autonomous space?

Second, they now confront me with another question. Why do I plan to leave the city and intend to stay in a lonely Himalayan village? I guess there are two reasons why they have this sense of wonder. Possibly, in this age of mobility, migration to cities in search of jobs and education, and the spread of consumer culture and the mythology of ‘good living’ through television channels, many of them have begun to believe that hope lies in the city which is a site of modernity, economic opportunities and human possibilities. They begin to see their own land as a place of difficulties and all sorts of constraints—no good school/college, no economic vitality, no job opportunity, no hospital, and everyday difficulty of transportation and movement in a complex mountain terrain. No wonder, they are surprised. When everyone loves to migrate to cities for better fortunes, why am I planning to undertake a reverse journey? Should not I miss the comforts of the city, its fast life? Should not I be bored in this ‘non-happening’ place with its ‘slow life’?

Furthermore, as I guess, they feel that possibly it is some sort of temporary romanticism on my part, and eventually I would realize my mistake, and go back to my city. Or is it that they think that I am privileged, I have got all the benefits from the city, and now I can afford to idealize the rhythm of a Himalayan village?

Do I denounce the city? Not really. Nor do I devalue the longing of these villagers for the city life. They have every right to see the limits to a static village, and strive for a good college for their children, a good hospital for medical emergency and economic opportunities for their dearest ones in a dynamic city. Moreover, who am I to degrade it when I have not yet been able to come out of it? As a matter of fact, when I go deeper and look at myself, I see the constant interplay of the two gunas or qualities of my being—rajas and sattwa. My rajas takes me to the city—its tremendous kinetic energy, its achievement and vitality, its speed and mobility, its market and competition, its performance and success. Yes, it has its role. It keeps the earthly existence alive. Even now when I am writing this piece from my Himalayan village, I can see my university—the packed library, students and teachers arguing, debating and learning; I can feel the vibrancy of the Connaught Place—its constant flow of people, its food joints and coffee shops, the activism of the Rajiv Chowk Metro station; I can feel what it means to be at India International Centre and watch a marvellous performance by a Bharatnatyam dancer. The city lives within me.

However, my quest for sattva takes me to this Himalayan village. Its calmness softens me; its silence purifies me; and its expanded range of mountains inspires me to build a bridge between the finite and the infinite. I experience a sense of humility when some old ladies of the village tell me that they are contented here, and the noise of the city tires them. When with absolute joy and ecstasy they show me the majestic Trishul and Nanda Devi peaks from their tiny pieces of agricultural land, I find yet another aspect of my being—my need for merger with the infinite, my longing for austerity and egolessness, and my quest for the ultimate surrender before the extraordinary mystery surrounding our existence. If the city is my outer self, the Himalayan village is my inner self. If the city is my career, the Himalayan village is my mother’s womb. If the city is my insurance for medical care and bank interest, the Himalayan village is my realization of the futility of egotistic pride.

I live with this dynamic interplay. I live in this fluid zone. Meanwhile, as I conclude this piece, from the windows of my village hut I see the clouds surrounding the mountain peaks; I see the distant valley; and I see a tiny bird flying into the sky. Is it the way God speaks to us?

***