It is not easy to engage with a saint-activist like Swami Vivekananda because from the oceanic current of ideas he represented, we often choose a fragment of it—and that too according to our politico-historical convenience. Not surprisingly, a charismatic figure like him with immense zeal and profound intelligence is often reduced into stereotypes: a ‘Hindu’ saint— an early ideologue of ‘cultural nationalism’; a ‘socialist’ wearing saffron—an inspiration for the revolutionaries in colonial India, or an icon for the youth; and an ‘organization’ man who put great emphasis on what these days NGOs regard as ‘social service’.

True, stereotypes are not unreal because they emerge out of some experience; yet, all stereotypes are partial, narrow and fragmented because human figures—particularly, creative personalities—live with contradictions, ambiguities and multiple possibilities. It is really a challenging task to have a nuanced engagement with Swami Vivekananda, especially because we live in a politically charged environment with strong emotive reactions. Yet, we ought to try.

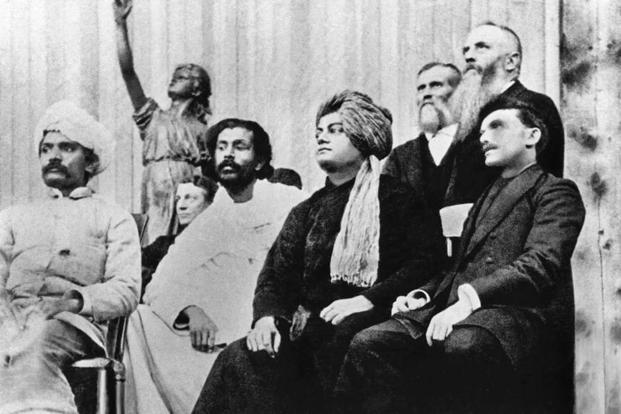

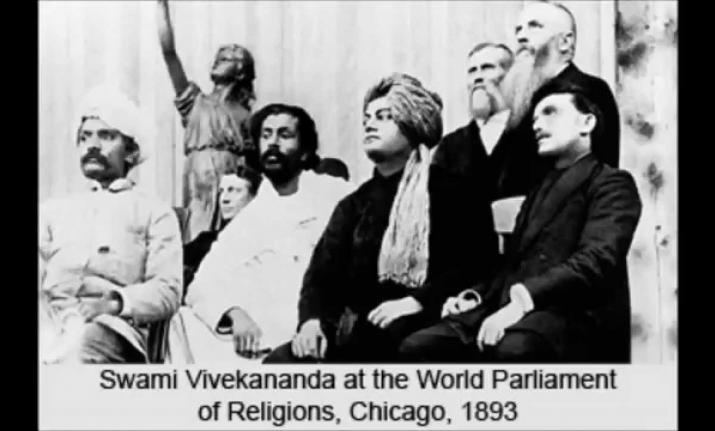

A section of the secular/liberal/left intelligentsia is not entirely wrong in pointing out some elements in the monk’s otherwise syncretic thinking (recall his Chicago speech: ‘As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee.’) that might have stimulated the Hindu Right to appropriate him. Take, for instance, his pride—even though very subtle—in ‘Hindu superiority’: why Hinduism, unlike other organized religions, is more accommodative, and why ‘our religion is truer than any other religion, because it never conquered, because it never shed blood, because its mouth always shade on all, words of blessing, of peace, words of love and sympathy’. If this ‘Hindu superiority’ is seen as a marker of our secularism, the fear is that it will always remain paternalistic and hence problematic.

Likewise, in the context of colonial politics that stigmatized and degraded the colonized, Vivekananda needed a distinctive Indian nationalism which, unlike the ‘economic’ nature of British nationalism or the ‘political’ character of French nationalism, would find its soul in religion. “ This is my method to show the Hindus that they have to give up nothing, but only to move on in the line drawn by the sages and shake off their inertia, the result of centuries of servitude”, said the passionate monk. Possibly, the equation that he established between religion and nationalism was not something that secular nationalists guided by the ethos of multiculturalism would plead for; instead, as the anxiety goes, it might have created the ground for the cultivation of the ideological roots of ‘Hindu nationalism’. And even modern feminists would feel rather uneasy with Vivekananda’s idealization of womanhood because in such idealization they would find neither equality nor the spirit of autonomous self-discovery but the essentialization of womanhood marking the moral character of the nation: “fearless women—women worthy to continue the tradition of Sanghamitra, Lila, Ahalya and Mira Bai, women fit to be the mothers of heroes!”

Yet, we would do injustice to the monk if we refuse to see anything beyond this because he was also the one who, like his master Ramakrishna, sought to go to the ‘mosque of the Mohammedan’, enter the ‘Christian’s Church and kneel before the crucifix’, and visit the ‘Buddhist temple’ to take ‘refuge in Buddha and his Law’ at his deep moment of longing and prayer. Moreover, to use Nehru’s language, he wanted to transcend the ‘dead weight of tradition’ through ‘Practical Vedanta’—a form of religiosity that finds itself beyond ‘forests and caves’, sees beyond mindless ritualism and orthodoxies, and , instead, seeks to awaken the innate potential in each of us.

Beneath our temporal/phenomenal/embodied existence lies the eternal energy—the all-pervading ‘Brahma’; and its realization makes one fearless because ‘all the powers in the universe are already ours’, and gives one immense energy to bloom like a flower. Yes, Vivekananda’s religiosity generated strength, not the tyranny of fear caused by the priests. It was this religiosity that inspired him to live like what Krishna in the Bhagavadgita pleaded for: an engaged karmayogi. It was a meaningful answer to Max Weber’s somewhat Eurocentric critique that, unlike Protestantism, Eastern religions are essentially ‘other worldly’. With his missionary zeal and action plan he could see the true affirmation of religiosity in one’s empathic understanding of people’s misery and suffering, or in selfless work for the liberation of the marginalized. No wonder then, in his writings and speeches, his sensitivity to the ‘coming age of socialism’ was distinctively visible.” Forget not”, said the monk at his most radical moment, “that the lower classes, the ignorant, the poor, the illiterate, the cobbler, the sweeper are thy flesh and blood, thy brothers.”

As we look at our times, we realize that Indian secularism is immensely vulnerable. If with a mix of ahistorical positivism and reductionist Marxism it negates the living tradition of an old civilization, it would remain elitist—confined to the charmed circle of the left/liberal intelligentsia. However, if it becomes too indulgent with ‘Hindu’ traditions, the result would be disastrous—the revival of Savarkar’s militarized Hindutva or Jinnah’s militant Islamic nationalism as a reactive gesture. Hence, Swami Vivekananda ought to be filtered and understood with great care and alertness. Only when we take his libertarian theology and reconcile it with Gandhi’s ‘experimental’ Hinduism, cross-religious conversations and spiritualized modernity can we move towards the making of a compassionate society.

Uttam is a theatre activist located in Siliguri, West Bengal.