SPECIAL STORY

In this exhaustive piece, the author has revisited Tagore’s novel Ghare Baire and Ray’s cinematic representation of the novel; here is an attempt to understand the tales of human emotions and aspirations.

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.

Engaging with a great piece of literature is not like covering the syllabus. It keeps calling you repeatedly. Ghare Baire ( The Home and the World)—a classic novel written by Rabindranath Tagore in 1916 in the context of swadeshi movement in Bengal—does not seem to disappear from my life. I read it again; and with the totality of my being, I felt it. With historical imagination, I felt the context—the political turmoil because of Viceroy Lord Curzon’s move to divide Bengal in 1905; and with empathy, I entered the inner world of Bimala, Nikhilesh and Sandip—the three characters Tagore portrayed with extraordinary sensitivity to human emotions, psychic/existential turmoil and spiritual longing. Reading is also like seeing. As I read the novel, it unfolds itself, and I begin to see them. I create my own Bimala, Nikhilesh and Sandip; I see Bimala playing the piano, Nikhilesh in deep communion with Bimala, and Sandip delivering a fiery speech on swadeshi. This seeing, however, gets another dimension when I watch Satyajit Ray’s film based on the same novel. While printed words make my ‘seeing’ deeply personal, the visual narrative of cinema is a public document created through the imageries of the filmmaker. Bimala is Swatilekha Chatterjee, Nikhilesh is Victor Banerjee, and Sandip is Soumitra Chatterjee; and when the filmmaker is no less than Satyajit Ray, the actors tend to merge with the characters, and a creative conversation begins to take place between these two modes of seeing, reading and experiencing.

The Subtlety of Tagore’s Literary Landscape

It is a great novel. Its every word, I believe, is written with poetic sensibility, deep psychic insight and profound philosophic vision. Like a great piece of literature, it is transcendental; even though written in a specific politico-historical context , it is essentially about love and freedom, desire and intoxication, rajos and sattwa, calmness and aggression, politics and ethics, the gross and the sublime. Furthermore, as it enters the deeper layers of consciousness of each of them, the experience of reading the novel is not merely descriptive or analytical; as a reader my heart aches; tears flow; I hear my heart beat; I become Bimala, Nikhilesh and Sandip simultaneously; Tagore ignites me.

Yes, here is Nikhilesh. He is a zamindar. But then, Tagore sees him beyond his class privilege. Nikhilesh is deeply humane—soft, calm and genuinely concerned about the well- being of people. The instantaneity of any magical solution in the name of the nation does not have much appeal to him. He sees the danger of this intoxication, its potential violence. His humanism transcends the idolatry of the nation. No wonder, even when the chanting of Vande Mataram, the euphoria of the swadeshi movement , the excitement of the crowd, and the passionate urge to boycott foreign clothes and goods come as a storm, like a sattwic yogi he remains calm; he refuses to be carried away. Yes, Nikhilesh marries a woman—Bimala—from a relatively simple background. But then, he is no patriarch. With tenderness and soft love, he wants Bimala to unfold her potential. She learns to play the piano; she learns English music from Miss Gilby (Jennifer Kendal)— a British lady. This openness leads Nikhilesh to persuade Bimala to cross the boundaries of the domestic domain, feel and experience the outer world. Nikhilesh believes that only after seeing the larger world if Bimala finds him, it would be the taste of real love; it would no longer be compulsion. His friendship seems to be unconditional. Even though his worldview differs from that of Sandip, they are friends. Sandip is the charismatic leader of the swadesshi movement. Finally, he arrives and becomes Nikhilesh’s guest.

What characterizes Sandip is his immense vitality—his rajosic urge to possess, conquer and dominate. Politics fascinates him; the sanctity of the ‘means’ makes no sense to him for achieving the end. With this recklessness, he becomes a charismatic leader of the swadeshi movement. His ‘aura’ has its appeal. He loves the pleasures of the world. Despite being a champion of swadeshi, it is impossible for him to give up his addiction to foreign cigarettes. In a way, he is strikingly different from Nikhilesh—the way calmness is different from aggression, narcissism from silent action, intoxication from meditativeness. Sandip knows that Nikhilesh does not agree with his political doctrine, his mode of being. Yet, they are friends; Sandip does not hesitate to receive financial help from his friend for the movement.

And Bimala is a woman torn between her devotion to her husband and fascination with Sandip. From the core of her heart, she knows the gentleness of Nikhilesh, his humanism, his expanded horizon and his openness. However, this peace in her life is severely disrupted as she crosses the walls of the domestic domain, and enters the world. The world comes to her as a storm with the presence of Sandip. In him Bimala discovers what she misses in her small world—the passion of the swadeshi movement, the magical vibrations of Vande Mataram, the life-energy of a charismatic hero. It becomes difficult to come out of his influence: the way he made her believe that as a woman she is special, and she can give new life to the movement. Without her husband’s consent, Bimala gives money and ornaments to Sandip for the movement. As they come closer and intimate, a psychic separation from her husband begins to inflict deep pain. Like the storm in the larger world, Bimala’s inner world too is disrupted. Is it like living with a sense of guilt and shame—the unresolved tension between the home and the world?

Nikhilesh sees and feels everything. He lives with his own pain; he does not impose his will on his wife because he believes that true love ought to emanate from the spirit of freedom; it cannot be imposed. Meanwhile, Nikhilesh’s refusal to cooperate with the militant protagonists of the swadeshi movement in his area (he knows that the poor people in his area—primarily the Muslims—cannot bear the cost of swadeshi; swadeshi products are costly; their economy survives on the basis of cheap foreign goods) makes Sandip restless. With his Machiavellian instincts, he succeeds in erecting a wall of separation between the Hindus and the Muslims. As communal violence erupts, Sandip leaves for another destination. It is Nikhilesh who enters the turbulent domain to restore peace; but then, he gets severely injured. Will he survive? The novel ends; the reader gets no answer. However, in this cycle of stormy events Bimala’s urge to return to Nikhilesh and merge with him once again remains unfulfilled. Moral virtues, or feminist assertion—did she lose both?

The Expressiveness of Ray’s Visual Narrative

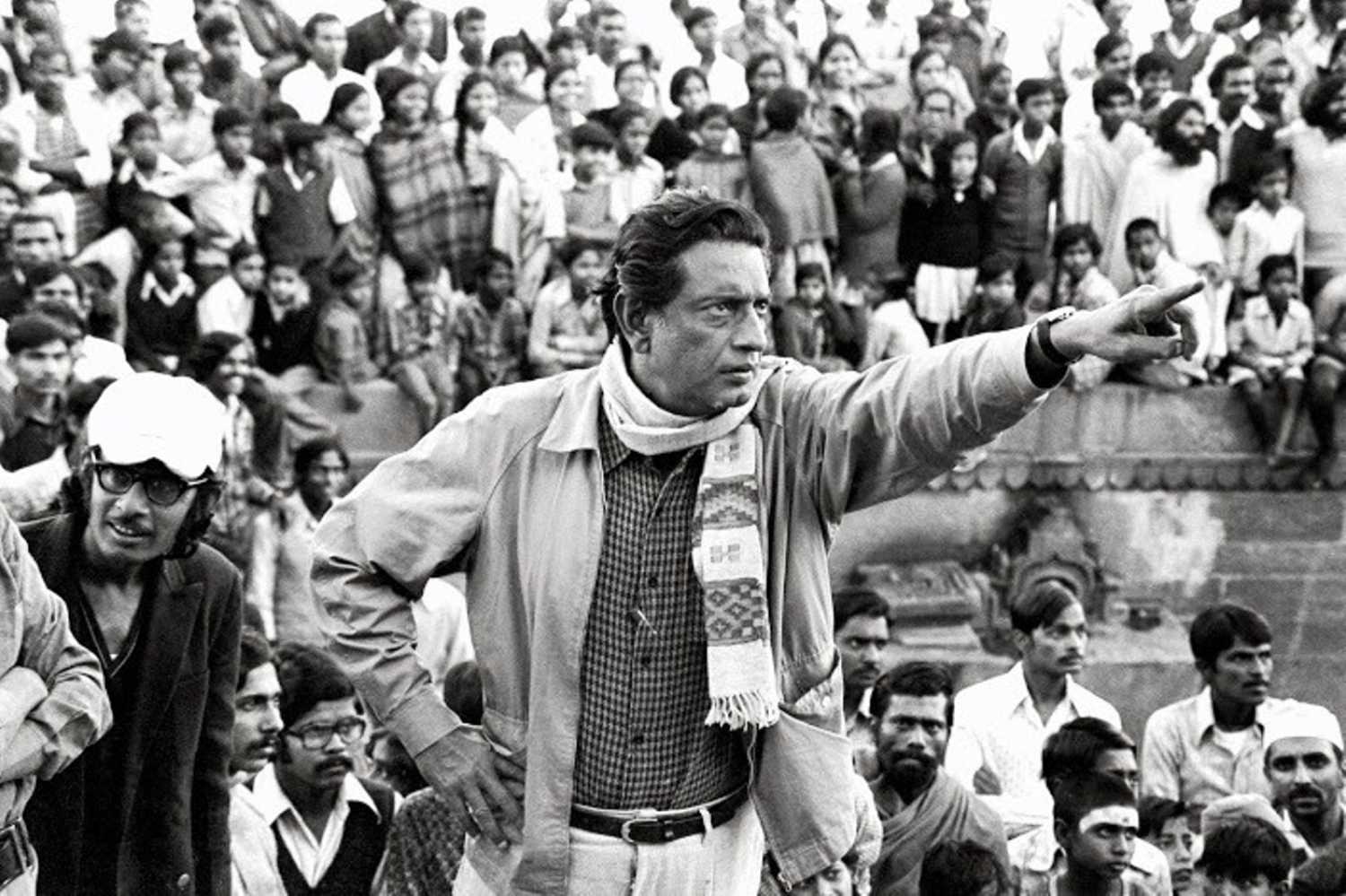

I know that this remarkably intense novel that draws the landscape of the interiority of these three characters is not easy to be translated into the language of cinema. Yet, when Ray— yet another classicist— chose to make the film, it aroused a great deal of interest. I saw the film when it was released in 1984. And the other day I saw it again. The visual narrative absorbs me. The film begins. Amidst the chanting of Vande Mataram I see Bimala (Swatilekha). Ray’s camera captures her remarkably expressive facial expression; it takes me to the inner turmoil of her mind: her pain and loss, her guilt and suffering. Slowly the film takes me to her golden days—her marriage, the slow and beautiful rhythm of her safe/secure world—the songs she sings, and the moments of tenderness and communion she shares with her highly sensitive husband Nikhilesh (VictorBanerjee). In their room which with its furniture and bottles of perfume (all foreign products) indicates the distinctive taste of her husband, I see a portrait of Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee)—Nikhilesh’s friend. Yes, he is coming. Like a gifted filmmaker, Ray captures the moment of arrival. Amidst the chanting of Vande Mataram he arrives with his disciples. As Bimala sees him from the balcony, listens to his fiery speech on swadeshi, something happens. Ray’s camera does the wonder. Once again I look at Bimala’s eyes; in those eyes I see what Tagore was revealing in his novel—her wonder, her infatuation. It is like the storm. With Nikhilesh her journey to the outer world is captured with great photographic delicacy. As she is introduced to Sandip, his eyes reveal everything—his charisma as well as his desire; his beard and shawl, and his ability to win a woman’s heart help us to know the character. Yes, the smoke of the burnt foreign cigarette seems to indicate his restless masculinity.

With great care, Ray shows Bimala’s tormented self, her dilemmas, her moments of intimacy with Sandip, her guilt, and eventually her realization, her ability to see the falsehood implicit in Sandip’s indulgent life and instrumental politics. With remarkable sensitivity, Ray captures her return, her urge to come back to Nikhilesh, and her final moment of surrender. The flow of her tears like the fountain of sorrow and self-purification, Nikhilesh’s tender touch, his wisdom and forgiveness emanating from the depths of his being—Ray’s visual narrative meets Tagore’s literary creation.

However, the world outside is burning. Nikhilesh cannot escape it. Bimala cannot stop him; he rides his horse, undertakes a journey; he has to save people from communal violence engineered by Sandip’s instrumental politics. Bimala’s union with Nikhilesh does not last; with agony, guilt and apprehension she waits; Ray takes us to that melancholic moment— people moving slowly towards their residence. Is Nikhilesh coming back? Is he alive? For Ray, Nikhilesh is no more. No words. The play of the camera makes it possible. It transforms her into a traditional Bengali widow with short hair and white sari.

As I write this piece, I see the world around me: the intoxication in the name of nationalism, the violent politics in the name of honouring the nation. I rediscover Tagore; I begin to realize the depths of his penetrating insights.