The pandemic led to the closure of schools across the country and as students were deprived of all educational exposure for a prolonged period of time, the idea of taking education online began to be exercised at a bigger level and online teaching-learning became the new normal. Online education in the form of online classes commenced after a prolonged wait all across the country but the inability to make the most of the new normal in education led many students in different parts of the country to take their own lives or to feel left out or distressed.

A Dalit girl set herself ablaze because she didn’t have access to an electronic device at her Wayanad home, and thus was compelled to miss out on her classes. Wayanad is one of the backward districts of Kerala. One of the most progressive states of India, Kerala had gone ahead with online classes in the beginning of June amidst the all pervasive reality that 2.7 lakh students still do not have access to electronic devices so as to be able to attend online classes.

The suicide of the Dalit girl had raised fundamental questions about whether students from the lower sections of the society have access to an adequate learning environment back home and whether they can make use of digital devices for availing online classes. Incidences of students committing suicide are not new to our immediate collective memory since a series of such tragic events have been reported periodically in educational institutions across India.

As was revealed in the Indian Parliament, 9474 students committed suicide in the year 2016 and it was the highest since 2012.

Some of the cases have received wider public attention and featured in the media debates for a long time as they were believed to be institutional murders more than just individual acts of suicide, whereas many others remained unknown and undiscussed.

These cases have reverberated continuous street protests, provoked activists and enticed the academic world.

The recent incident, as the preliminary investigation suggests, is the latest among these episodes of suicide and adds to the sustenance of the epoch of institutional murders.

The new forms of institutional discrimination certainly suffocate the students coming from extremely poor backgrounds, and they are left with no hope for a bright future and are driven into sacrificing their precious lives. This also exposes the everyday experiences of the poor in the so-called modern and enlightened educational spaces and the structural exclusionary practices. The latest issue points towards the discriminatory and exploitative practices entrenched in the institutional apparatus and highlights how educational accessibility has continued to remain a matter of privilege.

At a time when the world is confronting multiple forms of crisis with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government has proposed many initiatives to resume socio-economic activities after a prolonged nationwide lockdown. This out-of-the-box thinking by the regime though appreciated for long-term development, the slew of packages followed by a series of policy reforms are to be assessed with extreme caution. Although the pandemic has shaken the entire humanity, its unintended consequences upon different groups and communities vary depending upon the social and economic security measures available to people in the country with deep-seated structural inequality.

Along with alarming growth of death cases due to the COVID-19 infection, the images of the migrant labourers both alive and dead circulated in the media followed by a public outcry. This was simultaneous with an unprecedented lockdown that had catastrophic implications on the livelihoods of India’s poor. It is this vulnerable group in India which was made to suffer the most and bear the social cost of the lockdown to contain the spread of the virus.

Discourses on governance were brought to the centre stage as the union government faced severe criticism from many quarters after it failed to deal with the complications of the lockdown and this was widely reported by forums across the spectrum. Sensing the significance of immediate political intervention, the union government proposed many policy suggestions to revamp the system. Since the first phase of the first lockdown, apart from closing down the educational institutions affecting 32 crore students to curb the pandemic, the ministry of human resource development pushed the educational institutions to switch from regular classes to the online mode to continue teaching and evaluation, in a fashion that was undisturbed.

Without giving adequate attention to the structural inequalities and especially to the prevalence of educational inequality, the imposition of rules from above to shift from the conventional mode of teaching to the online mode, seemed to be inviting more trouble to the teaching and learning processes.

The Implications of a Sudden Shift: From Offline to the Online Mode

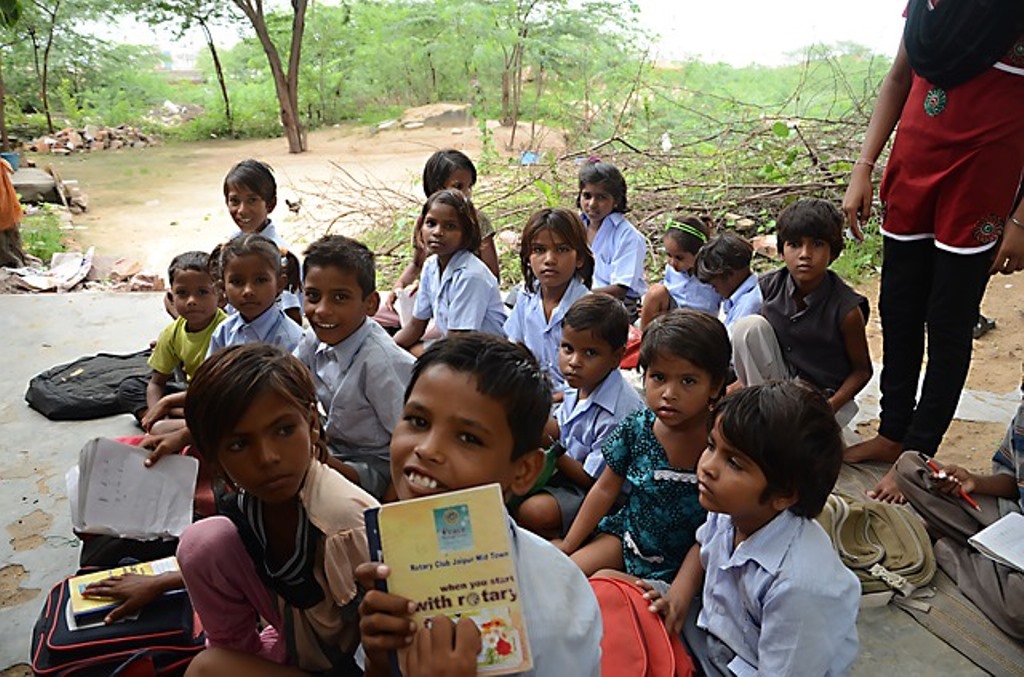

The sudden shift from the concrete/physical site of the classroom to the virtual/online mode unearthed several issues and challenges around the questions of educational accessibility, social hierarchy and differential access to educational opportunities in our society.

Therefore it becomes all the more necessary to take into consideration the existing structural problems embedded in our system. It would not be wrong to say that in the field of education, especially in a democratic society, we need a more critical view of the existing patterns, the complex functions and undesirable outcomes which tend to produce inequality in education.

The pattern of educational inequality and its persistence is a critical site to contextualise the problems, especially the social context of learning and learning processes which permits us to visualise a plan and outline doable programmes. In other words, any new adaptation to the educational system and its success should fundamentally depend on the preamble of social conditions in which the system rests.

Evaluation of the educational policies, practices and their outcomes in the last seven decades show our collective failure, which exposed the growing educational inequalities across gender, caste, tribe and religion as far as educational access is concerned.

This compels us to think about educational inclusiveness as the new paradigm of development that outlines policies for a sustainable future. Not surprisingly, among policymakers and analysts, the discourse on access, equity and quality has become a new political language needed to make education inclusive.

Educational Inequality

The expansion of the educational landscape in the last two decades has led to the growth of institutions and the enrolment rate both in schools and institutions of higher education. There are 1522346 schools in India (from primary to the senior secondary) and the educational statistics reported that the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GRE) has obtained a reasonably good number at the school level regardless of the students’ social backgrounds. But at the level of higher learning, stark differences were observed in the GRE and a low rate was recorded among the lower sections such as scheduled castes (19.9 %) and scheduled tribes (14.2%) against the overall rate of 24%.

Similarly, although the general dropout rate attained the lowest value (4%) at the primary level, it shot up (17%) at the upper primary level. It is to be noticed that the real expansion of the educational institutions was found much more in the private sector. The reason for the exponential growth in the private sector since 1990 was the laxity on the part of the government towards privatisation of education. Of the total 1.7 million schools, 38 % are in the private sector and its growth rate in the last decade has been 20 %. The private sector in India is the largest experimental laboratory of the market for school education in the world.

On the contrary, in government schools, the enrolment of students began to crumble down slowly. For instance, with zero enrolments there were 4464 (0.6 %) in primary and 2702 (0.7 %) in upper primary schools found in 2016. With an enrolment of fewer than 15 students, there were 55996 (7.1%) in primary and 22312 (6.1%) upper primary schools. Similarly, with less than 30 students there were 187006 (26.5 %) in primary and 62988 (17.3%) in the upper primary schools. The cause of the low enrolment rate in the government sector was attributed to the lack of availability of teachers and the low quality of teaching. There were 81459 (11.5%) primary schools and 14786 (4 %) upper primary schools with a single teacher. The elementary schools alone have reported the shortfall of teachers, where there were 9.08 lakh against the strength of 51.8 lakh posts in 2016. To rationalise the availability of the schools ,the government has closed down 31809 schools in the last four years as part of the school merger policy.

Selling the Myth that Only Private Schools Offer Good Education

Interestingly the places vacated by the government schools because of the low enrolment rate were replaced by new private schools. Behind this structural shift, a myth has been circulated among the public, including the poor sections that the private schools can only guarantee quality education. Somewhat, teaching English language and teaching in English became the main criteria to determine the quality of education. Creating such a myopic construct of education in the private sector has threatened the existence of the government schools owing to their low quality. With the changing public perception of education especially about quality, there was a great demand for private school regardless of urban and rural divides. Sensing the growing distress among the poor household to afford the cost of education in the private sector, a policy was framed to reserve 25 % seats in private schools for the backward sections of the society under the Right to Education Act 2009.

The loosely defined rules and regulations of this Act caused a new set of problems as the aim of the private sector was to protect the interest of the rich parents who pay heftily for the private gain of their children. Even if the private schools accommodated the children from the low-income groups , the parents didn’t find themselves in a position to demand improved learning levels, unlike their high-income counterparts. One can broadly dissect two inferences from it. Since the admission is obtained in the private school under the reserved quota earmarked for the poor household without charging a fee, the voices of the poor parents are hardly heard by the school management. Because of the low educational background of the parents and poor infrastructure in the family, the learning environment at home may not be viable for the students figuring under the low-income group.

Other than the periodical announcements of regulation and incentives, the state is left with no power to create enabling conditions of equality in the private schools. Discrimination and differential access on the basis of caste, class, gender or community were rampant. Therefore, the roots of educational inequality are extremely complex not merely because of the diversity and structural inequality in society, but also conditioned by the policy discourses, political economy and narrow ideological preoccupations prevailing within the educational system.

Often, the political interference of the reformist intellectuals, including the policy makers constraint the institutions of learning to perform their critical function. The compounding effect of these structural undercurrents certainly implicate the students who come from poor households the most, and have negative consequences on their learning.

Imposing online learning as a strategy of adaptation in the mid-way of crisis both by the state and private online service providers will complicate the lives of poor children because of their vulnerable living conditions, which have already worsened after the lockdown.

Technological Adaptation

Digital technologies, popularly known as Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are the latest additions in reforming school education. The national policy on ICT in school education underlines the purpose and significance of adopting technology in institutions at different stages. Broadly the policy outlines three major components. First, to establish and maintain the ICT infrastructure in schools and educational institutions. Second, special training for the teachers to adopt technology as pedagogical resources. Third, technology integration with educational institutions. A comprehensive national policy on ICT was initiated in 2012 to improve access, quality and efficiency of education. An integrated e-learning platform called ‘Study Webs of Active Learning for Young Aspiring Minds’ (SWAYAM) offers many courses for students, teachers and teacher educators under online mode along with the transmission of e-content through 32 national television channels under the banner of the SWAYAM PRABHA DTH TV. But it must be underlined that all these initiatives were designed only to supplement the regular teaching and learning processes within the ambit of the institutional spaces. Its mission was to build the capacities of students and teachers in ICT skills through computer-aided learning. Certainly, it is not designed for an online class amid crisis like in the open schooling system. However, neither the central nor the state governments have a better idea about the quantum of ICT infrastructure and skilled manpower and their availability across the length and breadth of the nation needed to meet the new demand of online teaching programme. On the other side of the spectrum, the private e-learning platforms have been using the crisis-time to expand their market opportunities.

India is a highly unequal society, hence access to technology for all young learners especially among the marginalised communities in the remote areas is a challenge for online mode of learning. Although television remains the most penetrated medium in India, it covers 100 million households (51 %) against a total of 193 million households in 2018. Similarly, 31 % of 480 million people are internet users and the smartphone users will certainly be less than this figure. But the usage of these devices exclusively depends on network connectivity across the region. Although diffusion of internet access is fast-growing, the facility access for women in rural areas and marginalised groups remains very poor.

Given such a situation, there is a clear digital divide among various socio-economic groups and geographical areas. Third, the learning atmosphere at home is a serious concern as most of the households in India lack optimal physical space for even basic dwelling.

Since 46 per cent of the households compose of one dwelling room and 31% have two dwelling rooms (Census 2011), one can easily imagine the extent of difficulties that the poor students could face in finding an environment conducive to online learning.

The intention of policymakers to integrate ICT in education is desirable on many counts. Developing several e-course contents in association with a selected number of schools and forecasting through online platforms and television channels are a small portion of the complex stages of adaptation of ICT in education. Though it is necessary but it is not adequate to adapt to the educational institutions to create a new ecosystem. Further, integration demands a participatory approach by involving the teachers in the school, community members and local governing institutions. The approaches and existing practices lack a comprehensive view of ICT in education to create a new ecosystem for inclusive learning. Given that the ICT architecture in education is moving on the opposite direction to minimise the political role of the state and maximise the market logic both in its content and outcome, the so-called new adaptation and integration would subvert the very idea of education as a social good.

In a highly feudal and patriarchal system with institutional and intellectual hierarchy, young learners are often seen at the receiving end of these discourses, no matter whether they are placed in the family or the school. The functional utility of the patron-client relationship is still found to be a comfort zone in the eyes of the administrative authorities and teaching community for discipline and good learning outcomes. In the policy on ICT in education one may sense how young minds get alienated from their childhoods because of these hegemonic impositions of the so-called new architecture of learning.

In a world characterised by globalisation and transformation, fast adaptation to these changes especially technological adaptation is necessary to fit this particular generation into the forces of the global market. Unless such adaptations are not well integrated into the entire spectrum of the population with the aim of expanding the public good, the online mode of teaching-learning will continue to pose new challenges for the poor sections of our society.

Suresh Babu G. S teaches at the Zakir Hussain Centre for Education , Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.