The Portrayal of Women in Satyajit Ray’s Films: Not the Usual Brand of feminism

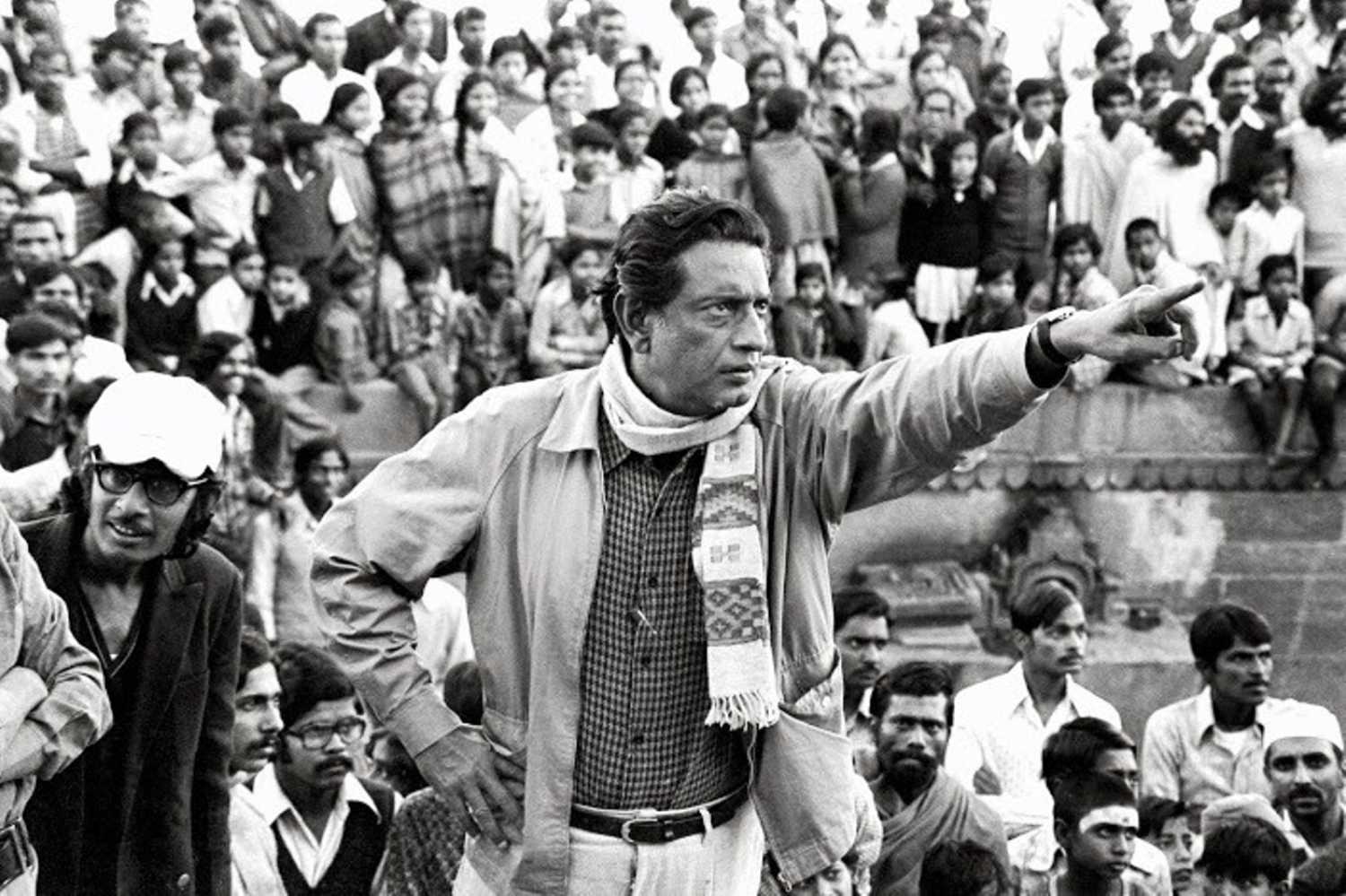

The artistic genius of Satyajit Ray lay in his ability to deal with very sensitive themes of collective concern yet without ever compromising on cinematic aesthetics. His films captured the essence of his times and are remembered for some of the most iconic moments in world cinema. Here, a researcher shares her insights on Ray’s genre of cinema particularly, the way he portrayed of women’s issues, and gave a more nuanced understanding of feminism.

By Writaja Samsal

As the film critics have said often, Satyajit Ray was ‘true to his times’. Indeed, Ray would perfectly capture in his films the 20th century ‘public’ panorama and people in their ‘private’ contexts. The master craft that Ray meted out focused more on the interplay of various characters on the screen, than the words they spoke. Most of Ray’s films are inherently simple, yet carried deep yet aesthetic messages. Although he was in a sense a regional film-maker, Ray’s appeal went beyond geographical or linguistic borders – due to the pervasive ability of his art to create a linkage between the local and the global.

Satyajit Ray was also well ahead of his times. His films, particularly between 1960 and 1985 reflected contemporariness in the sense that while the society was not yet able to fathom a separate existence of women other than in relation to men or the struggle inherent in such dynamic existences, Ray portrayed these images successfully in his various narratives – be it in Ghare Baire, Pather Panchali or Charulata. Yet neither of those films are aggressively women-centric or spew hatred against men, nor can they be labeled as representing any one ideological standpoint. Instead, in a very subtle manner Ray’s work proved that for the portrayal of women’s perspectives one need not necessarily undermine the contributions of men. In his films, female characters were usually carved out with special care. While the Apu Trilogy was mainly centered around the joys and struggles of a poor Bengali boy called Apu – the series stands true only with regard to its other characters, which are predominantly female.

Ray chose to show the ‘yatra’ or journey that women make under the gaze or threat of the male or Bengali society.[1] Therefore, Ray’s films were truly but not determinately feminist. This is to

buttress the fact that true feminism upholds women’s rights not at the expense of that of men. The feat that Ray achieved by recognizing the dualistic nature of social institutions as marriage, that often form the bedrock of feminist

argument – is reckoned in films as Kanchenjungha versus Apur Sansar. In the first, Ray brings out a light sarcastic view of arranged marriages, whereas in the latter, the type of marriage that primarily sets off Apu’s conjugal life is arranged. Thus, it can be safely said that Satyajit’s feminism did not take a biased, radical stance yet.

Ray’s vision of human relationships, in which women constitute an important part, was different from his contemporaries in the film world. Rather than trying to show men and women as equals or the opposite, Satyajit showed them as complimentary to each other.

His films as Mahanagar ought to show the real questions and challenges a woman faced in her life and how she would find solutions to them – while also bringing out the difficulties in reconciling various aspects of life – family and traditions, with individuality and career under the overtures of a rapidly changing society. Women on one hand were portrayed as simple yet latently complicated; on the other hand, they were powerful anchors yet ultimately vulnerable individuals.

While Ray’s films meant something special for women from all socio-economic classes, all the women characters in Satyajit’s films were also relevant to their historical and social contexts. Charulata showed the duality of the young educated Bengali woman who had to live within the ‘private’ sphere, four-walled domesticity while around her the world, the ‘public’ sphere was changing rapidly, demonstrated by her husband and her brother-in-law. In Mahanagar, Arati comes in slow contact with the urban culture influenced by the remnants of our ‘ex-rulers’, the Anglo-Indian Edith. In Pather Panchali, Apur Sansar and Mahanagar, the female characters belonged to lower-middle class households but in Devi and Ghare Baire, the characters lived in Zamindar mansions. In addition, in Aranyer Din Ratri, Ray explored the experiences of both urban upper middle class and rural, uneducated women in the backdrop of a tribal hinterland.

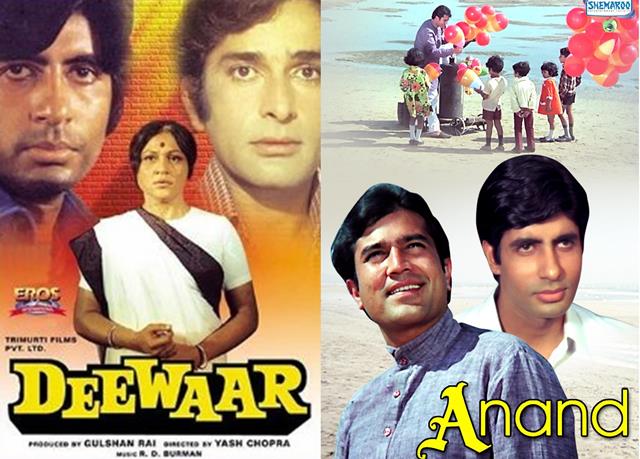

As Sudhir Kakkar has documented in his book Intimate Relations, commercial Indian films have traditionally portrayed women as either a ‘body for display’, colloquially known as the ‘eye candy’ or the good-natured, ritual-bound woman whose sexuality is uncomfortable, and liberality is unacceptable. However, reasons for such a stature of women in the society were never explored sociologically to the extent that the audience would be scandalized. Anecdotally, the Indian censor board had initially refused to authorize Devi’s international release ignoring the fact that in that film Ray’s illustration of the Hindu patriarchal ritualistic traditions and its impact on ordinary woman was meant not to expose India as superstitious and backward, but to show a ‘dialectical’ reality manifesting itself in a more complex way. This is to mean that the more matter-of-fact way of showing the reality without focusing on any one approach, viz., traditionalistic or modernistic.

No human being, man or woman, is always either black or white and the acceptance was made by Ray that there were grey areas of confusion and misperception enunciating behavior, something he was not afraid to show in his films. Both Charulata and Ghare Baire illustrated the dilemma women face between fulfilling the domestic role in the face of increasingly strong emotional and sexual feelings as they remain dissatisfied in their marriages. On the other hand, Manimalika in Teen Kanya was as real as an insecure and neurotic personality combined with material greed would be. In the same film, Pooty of Samapti demonstrated the wild, rebellious character a girl would have before society turns her into a woman.

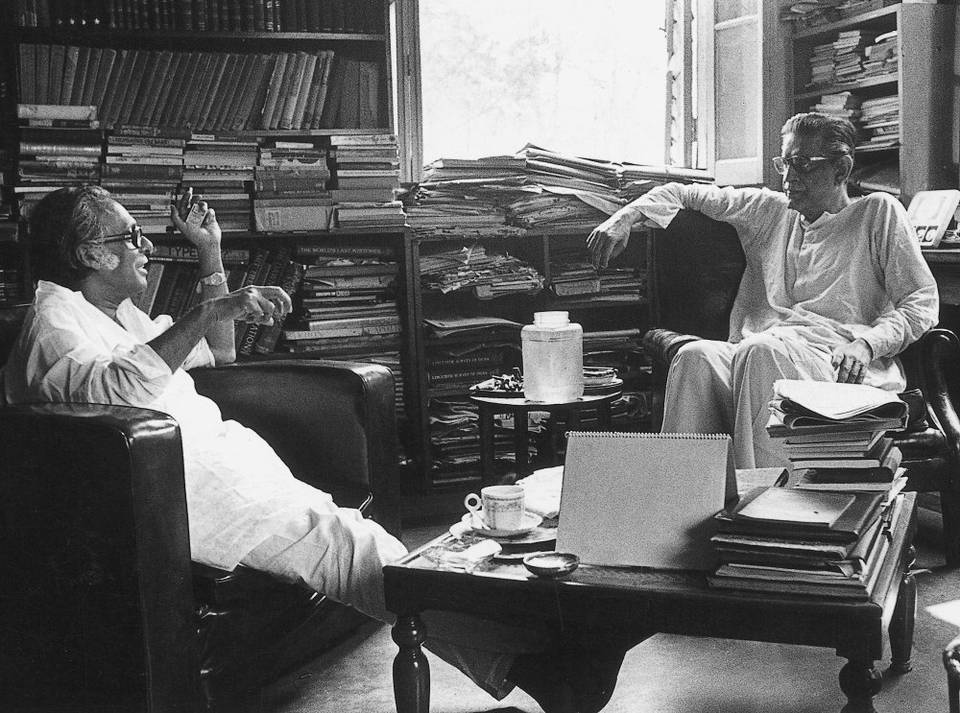

Ray effortlessly showed the multifaceted woman in both rural and urban settings – as a mother, a wife but also as a decision maker or a social butterfly. She was not secondary to, but also did not compete against men. The woman is effervescent, and complete in herself. Such portrayal of the female character by Satyajit can be attributed to his own experiences, his historical memories of belonging to one of the progressive Bengali families at that time. Being the grandson of Upendra Kishore Roy Chowdhury, the leading figure of Brahmo Samaj – Satyajit’s perspective was shaped by a free, independent image of a woman. But he skillfully recognized and recreated the vulnerabilities that come with power, the familial trade off that come with economic independence. Ray’s trilogy for children, however were stingy in incorporating women’s characters – for example, in the Gupi Bagha or the Feluda Series. His portrayal of women was mainly in family life, and around interpersonal relationships. In a sense, an oblivious bias towards the men to public and women to private life dichotomy is highlighted. Nonetheless, the fact that he made films sufficiently versatile to suit every audience, and his specific focus on a slew of films made especially with women at the centre of emancipation – make for this limited poverty of representation.

[Writaja is currently pursuing her master’s course in Strategic Studies at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore]