My commitment to engaged pedagogy is an expression of political activism. Given that our educational institutions are so deeply invested in a banking system, teachers are more rewarded when we do not teach against the grain. The choice to work against the grain, to challenge the status quo, often has negative consequences. And that is part of what makes that choice one that is not politically neutral. In colleges and universities, teaching is often the least valued of our many professional tasks. It saddens me that colleagues are often suspicions of teachers whom students long to study with. And there is a tendency to undermine the professorial commitment of engaged pedagogues by suggesting that what we do is not as rigorously academic as it should be. Ideally, education should be a place where the need for diverse teaching methods and styles would be valued, encouraged, seen as essential to learning. Occasionally students feel concerned when a class departs from the banking system. I remind them that they can have a lifetime of classes that reflect conventional norms. Of course, I hope that more professors will seek to be engaged. Although it is a reward of engaged pedagogy that students seek courses with those of us who have made a wholehearted commitment to education as the practice of freedom, it is also true that we are often overworked, our classes often overcrowded. For years, I envied those professors who taught more conventionally, because they frequently had smaller classes. Throughout my teaching career my classes have been too large to be as effective as they could be. Over time, l’ve begun to see that departmental pressure on “popular” professors to accept larger classes was also a way to undermine engaged pedagogy. If classes became so full that it is impossible to know students’ names, to spend quality time with each of them, then the effort to build a learning community fails. Throughout my teaching career, I have found it helpful to meet with each student in my classes, if only briefly. Rather than sitting in my office for hours waiting for individual students to choose to meet or for problems to arise, I have preferred to schedule lunches with students. Sometimes, the whole class might bring lunch and have discussion in a space other than our usual classroom. At O berlin, for instance, we might go as a class to the Mrican Heritage House and have lunch, both to learn about different places on campus and gather in a setting other than our classroom. Many professors remain unwilling to be involved with any pedagogical practices that emphasize mutual participation between teacher and student because more time and effort are required to do this work. Yet some version of engaged pedagogy is really the only type of teaching that truly generates excitement in the classroom, that enables students and professors to feel the joy of learning. I was reminded of this during my trip to the emergency room after falling down that hill. I talked so intensely about ideas with the two students who were rushing me to the hospital that I forgot my pain. It is this passion for ideas, for critical thinking and dialogical exchange that I want to celebrate in the classroom, to share with students. Talking about pedagogy, thinking about it critically, is not the intellectual work that most folks think is hip and cool. Cultural criticism and feminist theory are the areas of my work that are most often deemed interesting by students and Ecstasy 205 colleagues alike. Most of us are not inclined to see discussion of pedagogy as central to our academic work and intellectual growth, or the practice of teaching as work that enhances and enriches scholarship. Yet it has been the mutual interplay of thinking, writing and sharing ideas as an intellectual and teacher that creates whatever insights are in my work. My devotion to that interplay keeps me teaching in academic settings, despite their difficulties. When I first read Strangers in Paradise: Academics from the Working Class, I was stunned by the intense bitterness expressed in the individual narratives. This bitterness was not unfamiliar to me. I understood what Jane Ellen Wilson meant when she declared, “The whole process of becoming highly educated was for me a process of losing faith.” I have felt that bitterness most keenly in relation to academic colleagues. It emerged from my sense that so many of them willingly betrayed the promise of intellectual fellowship and radical openness that I believe is the heart and soul of learning. When I moved beyond those feelings to focus my attention on the classroom, the one place in the academy where I could have the most impact, they became less intense. I became more passionate in my commitment to the art of teaching. Engaged pedagogy not only compels me to be constantly creative in the classroom, it also sanctions involvement with students beyond that setting. I journey with students a they progress in their lives beyond our classroom experience. In many ways, I continue to teach them, even as they become more capable of teaching me. The important lesson that we learn together, the lesson that allows us to move together within and beyond the classroom, is one of mutual engagement. I could never say that I have no idea of the way students respond to my pedagogy; they give me constant feedback. When I teach I encourage them to critique, evaluate, make suggestions and interventions as we go along.. When students see themselves as mutually responsible for the development of a learning community, they offer constructive input.

The academy is not paradise. But learning is a place where paradise can be created. The classroom, with all its limitations, remains a location of possibility. In that field of possibility we have the opportunity to labor for freedom, to demand of ourselves and our comrades, an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries, to transgress. This is education as the practice of freedom. (203-205).

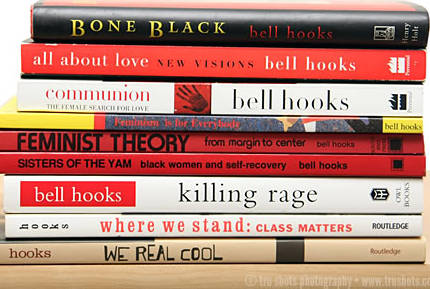

Source – Bell Hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education and the Practice of Freedom, Rutledge/Taylor and Francis, New York, 1994