Out of the current spate of movements in India and across the world some have achieved success while many have raised their heads only to fade out. The question naturally occurs as to why this is so. After all, movements are the expression of opinions and feelings of large numbers of people. Possibly an answer can be found if a comparison is made of the two movements led by Mahatma Gandhi – one the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920 and the Civil Disobedience Movement exactly a decade later. The first one was called off abruptly amid violence while the second forced the British to convene a second Round Table Conference with the sole aim of ensuring Gandhiji’s participation.

One important factor may have been that in 1920 Mahatma Gandhi was a beginner in India while over the next 10 years he not only gained in stature but also had a much better organised Congress behind him. But this was not his first shot at movements as he had already gained considerable experience over the years in South Africa where he tried out and achieved practical success by using the method of passive resistance. The explanation may be offered that the difference was in numbers – in India he had to deal with much larger numbers than in South Africa where the Indian settlers were only a few thousands.

During the first Non-Cooperation Movement Gandhiji adopted many of the key ingredients required for movements to succeed – clear and easy to understand issues and a plan of action. Chief among the issues picked up by him were the demands for action against those responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and addressing Muslim grievances against the Turkish Treaty.

If the government did not oblige Indians would non-cooperate in a phased manner starting with the simpler ones of giving up titles and honourifics, not attending official functions (the Duke of Connaught was due to visit India); not entering the legislative councils and moving on to boycott of government schools and official law courts and foreign cloth.

Later it would be ramped up to quitting government and military service and refusal to pay taxes. Yet, despite Mahatma Gandhi’s emphasis on non-violence as the principle underlying the movement, violence broke out and he called it off barely a year-and-a-half after it started much to the annoyance of many of his supporters just as it appeared to be picking up momentum. He himself was sentenced to a longish jail term that threatened to end his career as a political leader in India.

By contrast, the second movement started by Gandhiji in March, 1930 was a resounding success. The civil disobedience and boycott campaign kicked off by the Salt March not just revived the Congress but forced the British to acknowledge that it was impossible to ignore the primacy of the party in any negotiations to frame a new constitution. The Congress had made it clear that the commission for this purpose under liberal politician John Simon was unacceptable to them as it was all-white and ignored Indian opinion. It had also refused to join a proposed conference to discuss the new arrangement unless the British Government announced that the its goal was at least dominion status if not complete independence for India.

No doubt, one of the most important reasons for the great success was that the British had seriously underestimated the influence of the Congress whose popularity was indeed waning in the second half of the 1920s. The radicals were gaining ground everywhere as the Congress found itself at a loose end. Mahatma Gandhi himself had admitted that the party of violence was gaining ground and serious doubts had surfaced even within the Congress about the chances of success of a non-violent campaign. Some sought to shelve non-cooperation in favour of responsive cooperation.

Gandhi was released from jail due to ill health in 1924 but was yet to regain the position that he had acquired after the 1920 Special Session of the Congress in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose had not achieved the status they were to attain later.

In 1930 Mahatma Gandhi not only turned the tables on the British authorities but gained international fame by showing that passive resistance and civil disobedience were not just Henry Thoreau’s dream but could succeed in practice.

So, what was different in 1930 from the previous occasion? Chance and luck may have played a part but they appear to have been minor. Mostly it was planning and preparation in mind-boggling details. This is evident both in accounts that appeared in the media at that time and the eight-volume biography of Mahatma Gandhi by D.G. Tendulkar.

A Ringside View

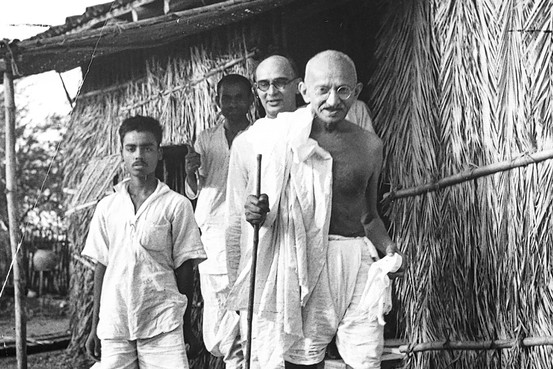

A ringside view of the march can be obtained from the April, 1930 edition of ‘The Modern Review’, a Calcutta English language monthly edited by one of the most prestigious editors of the time Ramananda Chatterjee. Among many photographs, one shows men and women lined up outside the Sabarmati Ashram before the march to Dandi on 12th March. It carried the caption, “The seventy-nine Ashramites who form the vanguard of the ‘Independence Army’ led by Mahatma Gandhi…” The editor wrote further that while it is easy to imagine armies, tanks, bombs and death and destruction, “…it requires some insight and imagination, some spiritual awakening, to understand, appreciate and be impressed by the march of an old unarmed man at the head of a few dozen of unarmed followers to break the iniquitous laws of the mightiest empire in the world in order to gain freedom for his people. However, the enemy may pretend to laugh, the stages and incidents of this historic march are being eagerly scanned by an expectant world, and the cables of the British Empire itself have to convey its news to London and perhaps to all corners of the earth.”

If reverence appears in the tone on the part of Chatterjee, it is to be clarified that he was among the most outspoken and independent editors of his time who did not hesitate to criticise even Gandhi when it warranted. It was very clear that the march was a momentous one even at that time and Mahatma Gandhi raised virtually to the status of a cult figure by Chatterjee who wrote, “Mr. Gandhi’s march is contemporary history. It is taking place before our very eyes. But if in some distant future it takes the shape of a mythical memory in the race consciousness, villages and towns may then vie with one another in claiming that the great-souled and pure-hearted meek liberator of his people passed through their byways and highways in his sacred pilgrimage and made their very dust holy.” Prescient thoughts.

Much more than luck, chance and circumstance, it was the deep thought and preparation ever since the passage of the Congress’s complete independence resolution of January 2, 1930 that went into making a success of the movement.

Gandhiji had in 1928 persuaded radicals like Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Bose to postpone for a year their demand for full independence rather than remain satisfied with dominion status. It is clear therefore that as early as 1928 he had become aware of the strong possibility of this push within the Congress particularly as the youth were getting disillusioned with the party’s inaction. By 1928 Gandhi knew that he knew that there was no escape from action that could ignite public enthusiasm.

Only a few days after the resolution was passed at Lahore but well before January 26, he hinted at how he planned the movement while talking to students of the Gujarat Vidyapeeth. For civil disobedience he would not rely on numerical strength but on the “strength of character of a few men sacrificing themselves for the cause.”

That explains why there were only 79 men selected for the march to Dandi. He was particularly alive to the possibility of the outbreak of violence which is why he was preparing possible volunteers to be prepared to stop violence even with their lives if required.

He also made it clear on February 27, just a couple of weeks before the march, that he would directly involve only inmates of the Sabarmati Ashram who had “submitted to its discipline…” though he admitted that he was hoping for a spontaneous mass response. Nevertheless, he was aware of the risks and issued a code of discipline that was published in ‘Young India’. The Satyagrahi must harbour no anger and be ready to put up with assault refusing to retaliate and must not resist arrest, among other strict rules.

The final 79 belonged to all corners of India and from Nepal and Fiji as well. Two of Gandhiji’s admirers from England – Madeline Slade (Miraben) and Reginald Reynolds – wanted to join the march but were not allowed to do so by the Mahatma who wanted them to stay at the Ashram to make sure that it carried on with its routine activities. Reynolds, a British Quaker and anti-colonial activist had been entrusted earlier with the task of carrying Mahatma Gandhi’s letter to the Viceroy informing him of his decision to start the movement. This he did to show that the movement was free from any racial motivation.

A comparison of the 1930 movement with the one that was started in 1920 shows several striking differences that certainly can account for the success of the former and the relative failure of the latter. For one, 1920 was a year in which the Congress was passing through the process of change of guard as the younger ones led by Gandhiji sought to take control of the grand old party that was already 35 years old. A Special Session of the Congress was held in Calcutta in September just to gauge support for Gandhi’s proposal of non-cooperation.

Though the non-cooperation resolution was passed by the Congress presided over by Lala Lajpat Rai, the vote remained a matter of controversy. In addition, there were many inside the Congress and outside who were not fully convinced that self-rule could be obtained through non-cooperation and non-violence. Two issues proved contentious– first the matter of whether to enter the newly formed councils under the 1919 Government of India Act which nearly caused a split in the Congress. Eventually, a compromise was reached and the Swarajist group formed under the leadership of Motilal Nehru and C.R. Das who decided to contest elections to the councils and fight the British administration from within. The second point in the programme that people objected to was the boycott of government schools.

But perhaps most of all, while the non-cooperation programme appeared to be lofty, the exact way in which it would force the foreign rulers out was not clear. Besides, it barely touched two to three percent of the Indian population since it was this number that could have anything to do with either schools or law courts. It resulted in several prominent Congress leaders giving up their legal practice. Above all, there were diverse agitations by workers and peasants as well as a revolt by the Akalis, and the Moplah uprising during that time, but there was no unifying symbol around which the movement could coalesce.

By contrast, in 1930 Gandhiji clearly specified that civil disobedience would consist of an act of defiance of the law – making salt and trading in it which was an illegal act. Around this single act the entire movement would revolve. Defying the colonial authority could be as simple as picking up salt lying on the seashore and trading in it – so simple that few had any difficulty in grasping it and carrying it out. Along with the action was also specified the consequences that followed this act of civil disobedience – arrest and imprisonment. Police brutality on this account was to be met not with retaliation but with non-violence. Not surprisingly defiance of the salt law spread like wild fire once Gandhi had bent down and broken the law by picking up salt in Dandi.

The Symbolic Selection of Salt

The choice of salt was ingenious because a number of reasons but foremost because it easily captured the popular imagination. First, its symbolism of faith that was recognized around the world. Second, it touched all sections of the people as everyone consumed it regardless of whether they were rich or poor and it brought out in sharp relief the evil of the system of empire that could tax such a basic commodity. Lastly, the march itself acted like a moving social media all through the 25 days that the marchers took to cover the 241-mile (385 km) stretch from Ahmedabad to Dandi.

In other words, it had just the right combination of those elements that make a movement succeed.

Kalyan Chatterjee was formerly Professor at Amity School of Communication, Amity University, India. He has worked as a journalist for over two decades, covering politics and government.