The decline in women’s participation in the Indian workforce reminds us of the importance of ensuring policy implementation at the grassroots and the critical significance of building conducive and equal work cultures.

Indrani Rai is a Women’s Rights Activist and Writer – based in Bhopal.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]omen are an important component of the workforce around the world. Their participation in the workforce is a widespread phenomenon of the modern times but what is paradoxical is the fact that women as part of the global workforce face the challenge imposed by inequality.

It is not a long time ago that many cultures and rituals around the world, discouraged women from taking part in the workforce. Women across the world continued to remain financially dependent on male members in their families in most parts of the world until much of the 19th century.

One of the reasons that excluded women from the workforce was the fact that for a long time women have been excluded from attaining the light of education and thereby have faced deprivation from high paying jobs in the economy. Even in the well-known universities like Cambridge, it was only as late as 1947 that women were admitted for higher degree in medicine and law.

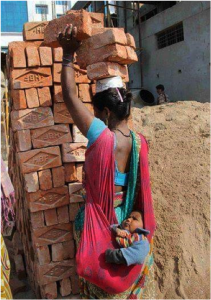

For the larger parts of the 19th and 20th century, women were limited to the low paying and low skilled jobs of the economy and were often given lesser pay than their male counterparts for the same amount of work. Even today, women’s participation in the workforce tends to be much below that of men around the world and it cannot be denied that unequal incentives, unequal access to promotion and credit, a safe and conducive work culture along with unequal access to education and opportunity are to be blamed f0r the disparity.

According to the World Bank Report (2017), India has one of the lowest participation of women in the workforce and ranks 120th among the 132 nations documented. India has 42% women who are graduates but despite this affirmative aspect, women’s participation in the workforce has been declining consistently since 2005. The report also brought to light that India’s GDP can be enhanced if it could enhance the number of women in its workforce. Most of the women who work in India’s workforce are employed in the agricultural sector and women’s participation in the service and industrial sectors is less than 20%.

There were myriad reasons that the report asserted could be leading to the fall of women’s employment and their participation in the workforce, these ranged from low incomes and associated drop-out from the workforce, lack of job opportunities, concerns about safety, lack of child care, enough payment and the absence of conducive norms that encourage women to participate in the workforce and reconcile work and home duties.

If we look at the statistics from India and compare it to other developing nations like Brazil, it is just 27% but in nations like Brazil it is 65-70%. The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) has produced its latest report which asserts that women merely composed 23.3% of India’s workforce between 2017 and 2018. One of the major reasons for this could be the aspect that there is an increased mechanisation of the framing sector and therefore a drop in the number of women employed. Agriculture is the sector in which we see most of India’s women workforce.

However, if we were to look at Bangladesh, we would be surprised to find that women’s participation in the workforce has increased because it has been able to strengthen the fabric manufacturing sector which has absorbed large number of women and given them widespread employment.

It is important that India creates decent work for women or else it will risk wasting half of its workforce and the opportunity to multiply its GDP. It is time that the nation took its women labour seriously and created work cultures that are suitable to encourage further women participation.

Of utmost significance in this entire project shall be the need to provide healthcare and maternity benefits to women across sectors, this will ensure that they don’t feel alienated and have a sense of dignity at work. Maternity entitlements in the form of compensatory wages and leave during pregnancy with adequate pay are recognised as part of women’s rights across the world. It must be acknowledged that only when such a mechanism is in place can we ensure that the mother has time and scope of feeding the young through breastfeeding and ensuring high levels of child nutrition.

It is ironic, that the legislative framework to ensure that women have a fair share in the labour force through a series of protective measures is quite weak in India.

The Maternity Benefit Act (1961) had been recently amended to increase the maternity leave period from 12 to 24 weeks. But what is ironic is that, while the act does seem like a positive step in ensuring that woman at work get dignity but the act leaves behind all those women who work in the unorganised sector- on the streets, as domestic labour, in farms and in many such spaces.

What is crucial to understand is the fact that more than 90% of women in India’s workforce are working in the informal sector and thus are not in the ambit of this act. Other legislative measures such as the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act (2008) does include maternity benefits for the unorganised sector but it has done little to link wages to the scheme of maternity benefits.

Under the purview of the Janani Suraksha Yojana(2005), an incentive has been added to institutional delivery but it says nothing beyond that. The only provision that can be seen to be enabling for pregnant women in contemporary women is under the Food Security Act (NFSA) that has assured that pregnant and lactating women get at least Rs 6,000. What must also be understood is the fact that while many of these policies do exist in terms of legislations, they are not implemented at the grassroot level.

To be able to get oneself registered for such benefits is a difficult proposition because in many places the labour laws are not stringent enough and labour unions are either not strong or unable to assert pressure on the employers. Moreover, being eligible for any policy demands tireless maintenance of documents and renewal that many workers find difficult to maintain. Given the fact that most workers in India’s informal sector are fleeting and do not works in the same place for long, the requirements have become difficult.

The fact remains that there are no bodies to ensure that women are getting maternity entitlements despite an array of legislation and policy interventions. It is time for the nation to rethink its maternity entitlements and ensure that women across sectors get such entitlements. There is also a need to ensure that maternity entitlements are unconditional, linked to wages and are applicable even when the employee begins work with a different employer. Moreover, the state has to play a more active role between the employer and the employee and ensure that maternity entitlements may be implemented.

The need for gender equity in employment too is crucial. Lastly, the delivery of maternity entitlements should be decentralised and labour boards should be taken on board at state and regional level. We also need to work towards creating awareness throughout the nation for women’s maternity entitlements and encouraging women participation in the workforce.