Over the past century half of the world’s ponds and wetlands have been destroyed, with many being filled in and turned into agricultural land. However, all is not lost, and it is possible to “resurrect” these buried habitats from the seeds and eggs stored within their historic sediments. A new conservation approach pioneered by the UCL Pond Restoration Research Group can restore aquatic habitats lost to the landscape for centuries.

Ponds can be extremely biodiverse. They support more aquatic species than any other freshwater habitat and provide important food sources for farmland birds and bats.

At the start of the 20th century there were an estimated 800,000 ponds in England and Wales – now, it is thought that fewer than a quarter of these remain. Similar levels of pond loss have occurred across farmland in Europe and North America, associated with increasing intensification of agriculture. Pond and hedgerow loss are often linked as hedges are uprooted and used to fill in ponds, before ploughing over the entire area.

Emily Alderton, Author provided

Many lost ponds leave behind a “ghostly” mark in the landscape – visible as damp depressions, areas of poor crop cover, or changes in soil colour. Colleagues and I have recently discovered that these buried “ghost ponds” are not completely lost, but can be resurrected from historic seeds lying dormant underneath intensively cultivated agricultural fields.

These ghosts are an abundant yet overlooked conservation resource. Resurrecting them would of course mean more ponds, which in turn links up aquatic landscapes as plants and animals jump from pond to pond and species are able to thrive in larger populations. But the main advantage of a ghost pond, compared to a new pond, is the historic seed bank buried below the surface. This provides a source of local native species, speeding up the process of colonisation, and potentially restoring lost populations or even locally extinct species to the resurrected pond.

We already knew that aquatic seeds were able to survive dormant for centuries within existing lakes and wetlands. Scientists recently tested 13 lakes in Russia, for instance, and found stoneworts (a keystone species in aquatic habitats), could grow from 300 year-old spores collected from lake sediments.

However, our recent paper, published in the journal Biological Conservation, is the first to demonstrate this astonishing survival ability within habitats which had been assumed lost to agriculture. In our study, we resurrected three ghost ponds in north Norfolk, eastern England. These ponds were similar in type, location and surrounding land use to the 8,000-plus ghost ponds buried across Norfolk and many more across the UK. While buried, ghost ponds are subject to the typical stresses of intensive agriculture (soil compaction, fertiliser and herbicide use), making the long-term survival of their aquatic seed banks particularly astonishing.

Our three study ponds had been buried for around 45, 50 and 150 years. Each was re-excavated down to the pond’s historic level, which was easily distinguished from the overlying topsoil by its dark colour, silty texture, and even its distinctive “pond smell”. This layer of sediment was left mostly undisturbed to provide the source of historic seeds and eggs within each pond.

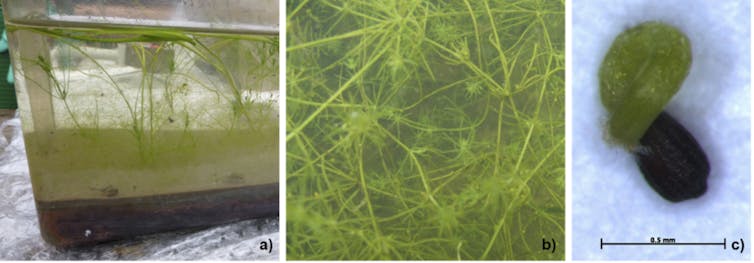

All three ghost ponds were colonised within six months by native plant species. In total, 12 species of aquatic plant colonised the ghost ponds and eight of these species proved to have originated from the seeds that had lain dormant below the ground. To check these plants really had grown from the ghostly remains of the previous pond, and hadn’t been carried in by the wind or seed-eating birds, we kept some of the historic sediment in sealed aquariums. There, even under controlled conditions, the same species still grew out of this centuries-old sediment.

Species recolonising from the historic seed bank included stoneworts, which are important for maintaining water quality but are increasingly threatened in farmland, and floating leaved pondweeds, which provide key habitat for dragonflies and damselflies. We also found crustaceans including Daphnia (water fleas), and copepods (tiny invertebrates which swim in a jumpy motion using their antennae), were able to hatch from eggs buried in the ghost pond sediment samples.

Although only common species were resurrected from the sediments of our three ghost ponds, these included seeds of all different sizes and types – from a variety of aquatic plant species. This suggests that a wide range of plants, including potentially rare or even locally extinct species, could potentially survive within the buried sediments of ghost ponds. The boost to recolonisation speed and diversity from the historic seed and egg bank may also reduce the risk of invasive species becoming established.

Ghost ponds represent abundant yet overlooked biological time capsules. Their restoration could facilitate the rapid return of wetland habitats and aquatic plants into the agricultural landscape. This process could play a significant role in reversing some of the habitat and biodiversity losses caused by the global disappearance of agricultural wetlands – and I urge conservationists to make use of this valuable yet hitherto little considered resource.![]()

Emily Alderton, PhD student in Aquatic Ecology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.