A new study reports that, at the current rate of progress, the National Nutrition Mission, India’s latest strategy in fight against malnutrition, will not be able to meet its 2022 targets to reduce malnutrition in India. And this is despite the reduction in malnutrition achieved by India in the 27 years up to 2017.

According to FAO, India had 195.9 million undernourished people-or people with chronic nutritional deficiency-in 2015-17, which had come down from 204.1 million in 2005-07. Moreover, the prevalence of undernourishment had gone down from 20.7% in 2005-07 to 14.8% in 2015-17 as well.

But India, FAO added, still accounted for 23.8% of the global burden of malnourishment, and had the second-highest estimated number of undernourished people in the world, second only to China.

In December 2018 IndiaSpend also published an analysis that India was not on track to achieve its 2025 nutrition target which was crucial to achieve its zero hunger by 2030 target. The analysis was based on the data from the 2018 Global Nutrition Report or GNR 2018.

The GNR 2018 had highlighted that although India had shown improvement in reducing stunting in children, the country was still home to over 30.9% (about 46.6 million) of all stunted children under the age of five – the highest in the world.

With this on-going crisis and continued debates over the negative impact of malnutrition on the population’s productivity, and its contribution to mortality rates in the country, across generations, the NITI Aayog in 2017 had released the National Nutrition Mission. The aim of the strategy is to achieve “Kuposhan Mukt Bharat” or malnutrition-free India.

Under the new strategy, the National Nutrition Mission or Poshan Abhiyaan set an annual target of 2-percentage-point reduction in the prevalence of low birth weight and child underweight, a 25% fall in the prevalence of child stunting and a 3-percentage-point annual decline in the prevalence of anaemia among women and children under five years of age.

According to the latest statistics published in The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health journal, however, if the National Nutrition Mission continues to progress at the set pace, relative to the 2022 targets, there will be an 8.9% excess prevalence in low birthweight, 9.6% in stunting, 4.8% in underweight, 11.7% in anaemia among children and 13.8% in anaemia among women.

In simple terms, the mission will fail to achieve even its set targets.

But why is malnutrition so problematic?

Malnutrition indicates that children are either too short for their age or too thin. Children whose height is below the average for their age are considered to be stunted. Similarly, children whose weight is below the average for their age are considered thin for their height or wasted. Together, the stunted and wasted children are considered to be underweight – indicating a lack of proper nutritional intake and inadequate care post childbirth.

In 2017, Malnutrition was found to be the predominant risk factor for death in children under five years of age in every Indian state, accounting for 68.2% of the total deaths in that age group, according to the researchers.

Malnutrition has also been the leading risk factor for health loss across all ages, responsible for 17.3% of the total disability-adjusted life years that denotes the years of potential life lost because of disability.

The major factors contributing to the country’s malnutrition problem have been found to be Low birth weight, premature births and poor exclusive breastfeeding habits. The study also highlighted the biggest factors that lead to higher malnutrition in children were low birth weight and poor exclusive breastfeeding. One in five children (21.4%) was born with low birth weight or under 2.5 kg, and only half of all children were exclusively breastfed (53.3%).

The most crucial factor however is the vicious cycle of poverty and malnutrition, passing on from generation to generation. Mothers who are hungry, anaemic and malnourished produce children who are stunted, underweight and unlikely to develop to achieve their full human potential.

The lack of nutrition in their childhood years therefore reduce their mental as well as physical development.

These disadvantaged children then do poorly in school and subsequently have low incomes. Further, providing poor care for their children continuing the intergenerational transmission of poverty and malnutrition.

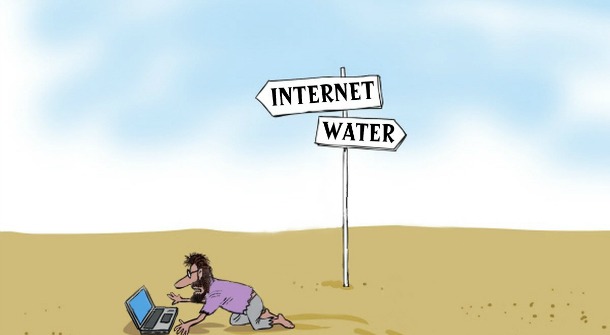

Malnutrition is however a complex and multi-dimensional problem. It’s causes are several factors, which included poverty, inadequate food consumption, inequitable food distribution, improper child feeding and care practices, inequity and gender imbalances, poor sanitary and environmental conditions, and moreover restricted access to quality health, education and social care services.

The study has thus stated that the malnutrition indicator targets set by the National Nutrition Mission for 2022 are rather aspirational and the rate of improvement needed to achieve them is much higher than the rate observed, making it difficult to reach the targets in short period of time.

This is, however, not the first time a scheme is faltering to accomplish its objectives.

Since independence, various government initiatives have been launched over the years seeking to improve the nutrition status in the country. These include the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), the National Health Mission, the Janani Suraksha Yojana, the Matritva Sahyog Yojana, the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, and the National Food Security Mission, among others. However, concerns regarding malnutrition have persisted despite improvements over the years.

The latest in the line, National Nutrition Strategy, had therefore been released in light of the previous schemes’ failures. But the statistics predict another faltering future.

India had been increasing food self-sufficiency and food security with the Green Revolution that since late 1960s. Despite that India continues to have a high prevalence of malnutrition, combined with an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in a subset of the population. Addressing this persistent development problem would therefore require India to ensure implementation of practical and effective policies and interventions. Robust estimation of malnutrition indicators and their trends over time would also be needed at the district level to understand intra-state variations.