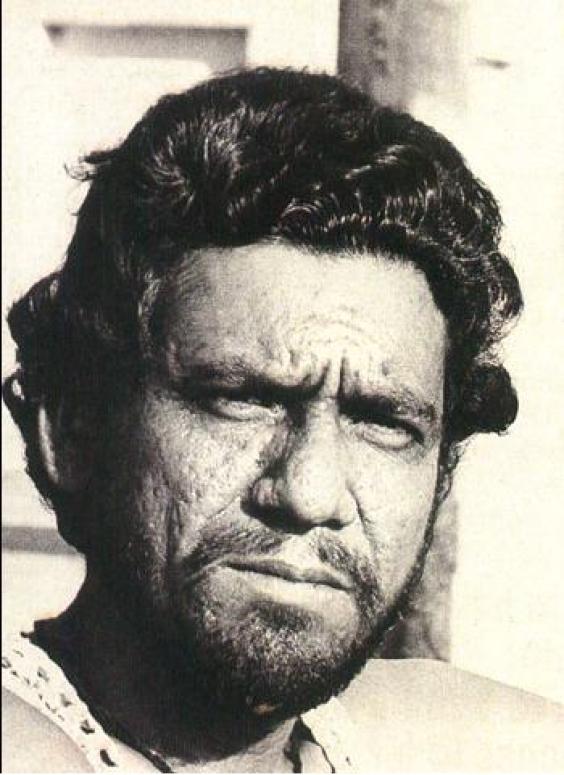

Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017) was one of those rare thinkers who could reconcile serious academic thinking and deep passion for a better world. Unlike many modern sociologists (think of Pierre Bourdieu, Jurgen Habermas and Jean-Francois Lyotard) his distinctive feature was his extraordinary capacity to communicate his ideas in a manner that touches one’s soul. His analytical skill, his beautiful prose and his clarity made him immensely popular amongst students, teachers and researchers. We know that the classical sociological tradition gave us the ‘landscape’ of modern/industrial Europe. Despite the celebration of the new age, we came to know about heightened differentiation , division of labour and anomic disorder; bureaucratization, rationalization and disenchantment; and alienation and class conflict—the social processes that characterized modernity during the late 19th and early 20th century. However, with the passage of time and major historic transformations, we found ourselves amongst a galaxy of thinkers who could see the discontents of modernity, its dialectic and contradictions—the emergence of a society characterized by the onslaught of ‘culture industry’, the ‘colonization of the lifeworld’ and the ‘micro-physics of power’ with its nuanced practice of discipline and surveillance. The fall of the Soviet Union, the hyper-real era of simulation and globalization, and above all, the postmodern debunking of all ‘solid’ foundations of modernity—Zygmunt Bauman was continually reflecting on his times. And his major works gave us a new sensibility—a sense of profound humanism. Yes, he could see the horror of the holocaust as a consequence of a mode of thinking that modernity itself cultivated—instrumental reasoning, dispassionate objectification, science dissociated from ethics and the arrogance of ‘certainty’ that seeks to eliminate all ‘unlicensed differences’. Again, he could engage with postmodernity in a refreshingly innovative manner. Modernity as the Enlightenment project sought to universalize itself with its ‘grand narratives’—the supremacy of modern science, the superiority of western living and its ‘legitimate’ right to impose its gospel of progress on the rest of the world. This ‘certainty, Bauman would argue, was over because of the awareness of the crisis of modernity, the assertion of diverse cultures, and the overproduction of a media-induced consumption pattern that delegitimizes the aesthetic judgment of the classicists and modernists. Under these circumstances, postmodernists do talk about fragments, differences, and end of grand truths. Bauman saw the emergence of a new intellectual tradition—‘interpreters’ of diverse traditions without moral certainty as opposed to ‘legislators’ burdened with the baggage of modernity and its ‘solid foundations’. Even though this postmodern condition or ‘liquid modernity’ creates the possibility of fluidity, hybridity and perpetual flux, it also causes ‘ethical paradox’—a sense of moral relativism , a state of being without solid/enduring relationships. Indeed, Zygmunt Bauman made us think. And The New Leam is paying its homage to this amazingly insightful Polish sociologist/philosopher by publishing select passages from one of his major books—Intimations of Postmodernity.

(I) The Ethical Paradox of Post modernity

The ethical paradox of the postmodern condition is that it restores to agents the fullness of moral choice and responsibility while simultaneously depriving them of the comfort of the universal guidance that modern self-confidence once promised. Ethical tasks of individuals grow while the socially produced resources to fulfill them shrink. Modern responsibility comes together with the loneliness of moral choice.

In a cacophony of moral voices, none of which is likely to silence the others, the individuals are thrown back on their own subjectivity as the ultimate ethical authority. At the same time, however, they are told repeatedly about the irreparable relativism of any moral code.. no code claims foundations stronger than the conviction of its followers and their determination to abide by its rules. Once embraced, the rules tell what one must do; but nothing tells one, at least convincingly, why these rules (or any other rules for that matter) should be embraced in the first place. The deposition of universal reason did not reinstate a universal God. Instead, morality has been privatized.; like everything else that shared this fate, ethics has become a matter of individual disposition, risk-taking, chronic uncertainty and never-placated qualms.

This is because behind the postmodern ethical paradox hides a genuine political dilemma. …If I consider corporal punishment degrading and bodily mutilations inhuman, letting the others to practice them in the name of their right to choose (or because I cannot believe any more in the universality of moral rules ) amounts to the reassertion of my own superiority: ‘they may wallow in barbarities I would never put up with…that serves them right, those savages.’ The renunciation of the monologic stance does not seem, therefore, an unmixed blessing. The more radical it is , the more it resembles moral relativism in its behavioural incarnation of callous indifference.

There seems to be no easy exit from the quandary. Humanity paid too high a price for the monologic addiction of modernity not to shudder at the prospect of another bout of ordering-by-design and one more session of social engineering. …If the civilizing formula of modernity called for surrendering at least part of the agent’s freedom in exchange for the promise of security drawn from (assumed) moral and (prospective) social certainty, postmodernity proclaims all restrictions on freedom illegal, at the same time doing away with social certainty and legalizing ethical uncertainty. Existential insecurity—ontological contingency of being—is the result.

(II) Legislators and Interpreters

The other side of philosophical certainty was cultural self-confidence. It was the latter that gave the unreflective and unyielding resolution to that Europe’s missionary zeal, for which the colonial episode of modernity was so notorious. …The conviction of the objective superiority of the social order formed in the north-western trip of the European peninsula was not partisan in terms of European politics. It united the intellectuals regardless of their political allegiance, or declared class loyalty. Cultural ideology was shared , as was its underlying premise that the human world has been always man-made, that the time has arrived to make it in a conscious, reasonable manner, and the way contemporary society has been organized opens the way to it. To put it bluntly, the intellectuals’ self-identification with what they articulated as ‘western values’ could (and did) remain unfaltering as long as the expectation that the western sociopolitical system would be hospitable to knowledge-based (i.e. ‘rational’) sociopolitical blueprints, could be seen as plausible. This expectation suffered many blows, and finally yielded to the accumulated pressure of adversary evidence; its slow and painful demise was only partly concealed by occasional, always short-lived, resurrections.

When related processually, rather than juxtaposed laterally, ‘legislative’ and ‘interpretative’ strategies can be recast as , respectively, ‘modern’ and ‘postmodern’. Indeed, the recently fashionable opposition between ‘modernity’ and ‘post modernity’ makes most sense as an attempt to grasp the historical legacy of the last centuries, and he most crucial discontinuities of recent history, from the perspective of the changing social position and function of the intellectuals. The post-modernity/modernity opposition focuses on the waning of certainty and objectivity grounded in the unquestioned hierarchy of values, and ultimately in the unquestionable structure of domination; and on the passage to a situation characterized by a coexistence of values and a lack of the overall structure of domination, which makes the questions of objective standards impracticable, and hence theoretically futile.

SOURCE: Zygmunt Bauman, Intimations of Postmodernity, Routledge, London and New York, 1992.

This article is published in The New Leam, MARCH 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.22 – 23) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.