The New Education Policy 2020 states,“Education is the single greatest tool for achieving social justice and equality”. As per the NEP 2020 inclusive and equitable education is critical to achieve an inclusive and equitable society in which every citizen has the opportunity to dream and thrive. Here one must understand that a citizen is not a singular and independent identity. For an educational policy, a citizen is the learner or a student present inside the educational institution or the School. The school is a space shared by learners from different class and caste groups, gender and ethnicities. This article attempts to shed some light on the education of girls with a special focus on caste and religious locations and identities in the context of social and educational inequality in contemporary India. It also asks some questions to understand the stand of the state on education of women/girls and what it recommends to improve the present situation.

What does it mean to be a Girl and a Woman?

Let us begin with a few questions a woman or a girl might have in mind in relation to identity. Who is a woman? Who is a girl? What does it mean to be a woman or a girl? What is the identity of a woman or a girl? With identity one can understand the aspirations, the relations and the positions of the individual within the society. Being a Dalit woman from an urban middle class family I see various identities of women around me. I see individuals playing diverse and difficult roles like a partner, teacher/guide, employee, labourer, mother, daughter, daughter-in-law, sister, friend, and mother-in-law. Hence I believe and I quote “woman or girl is not a singular identity. It is enmeshed in social structures, practices, rituals, cultures and customs. It is reproduced and legitimized by institutions like family, religion, caste, education, law, media and state”. If there are points of divergence then there are some points of convergence as well. Womanhood is a temporal and spatial dimension. It is diverse with spaces be it public or private & urban or rural, with socio-economic class, with religion and caste. Now it is important to look at the childhood of a woman. The question arises, how and why is it different? To find the answers, we can observe the restrictions which have been put on girls in terms of boundaries to control their physical mobility, free time, interactions, desires, decision making, and by moral policing and to respond to the question of ‘why’ there are social & cultural norms, growing patriarchy and control. I find it difficult to use the term ‘childhood’ with reference to ‘girls’. There are some very significant dimensions regarding the upbringing of girls in families as well as society i.e. it is not universal for all. It is in the routine of a girl’s upbringing to behave in a certain way to mould them into being able to fit in a predefined role. The term ‘girlhood’ refers to this mould, shaped through culture over the ages, that imprints on the mind of the female child from the earliest stages of development. The imprinting is about forcing certain ideologies, putting certain patterns about one’s expected role, responsibility and status. Hence, it would be only following a pattern when we incorporate girlhood into childhood. Girlhood is a stage of preparation for womanhood. Girls are socialized at their ‘temporary’ homes to behave in a certain manner to reproduce that skilled and cultured behavior in their permanent home after marriage. For a socially sanctioned girlhood it becomes important to be prepared from certain fears. These fear functions at both the places inside and outside the home. There are three levels of fear. One is fear of bodily injuries while playing sports. This creates an anxiety about a distant consequence. Second is sexuality, there is a communicative gaze of adults to control a girl’s sexuality to force her to achieve an identity of an acceptable woman. Third is fear of freedom from a fully merged/dissolved into socially authorized identities. Since the very beginning they are learning submission to be at inferior status. The idea of freedom (freedom from fears) arises from the idea of child rights. The idea of freedom, enjoyment, free from boundaries is absent from the lives of girls. Besides family various other institutions affect the upbringing of a young woman like education, religion and caste. Hence it is important to throw some light on the education of girls inside and outside institutions such as school and family in the context of caste and religious groups.

Education for girls and its goals

Why do we want education for girls? What kind of education will be important and useful for girls and who will educate them? What kind of institutions are safe spaces for girls? All of these questions impact the larger aim of girls’ education. One can find many possible answers to these questions if one understands the goals of education. In context of Muslim women Zoya Hasan, an Indian academic and political scientist (2008) shares that besides sending children to Madarsa muslim women recognized the importance of school education especially for their girls. They desire a change and they believe education could give them a better chance for upward mobility. One can understand that muslim women recognize the absence of education in the lives of their children. For brahmin families educating young women improved the social outcomes of their children and families. It also serves as a status achievement to secure higher ‘bride price’ and related social benefits. On the other hand, provision of schooling for Dalits was an important and positive step toward challenging the caste system oppression. So one can observe the goals are different for different social groups belonging to religion and caste. Here comes the role of the state to take some actions for education for girls. State makes a policy to communicate what all it is planning to do in the future which has not been done in the past.

National Education Policy 2020 on Girls’ Education

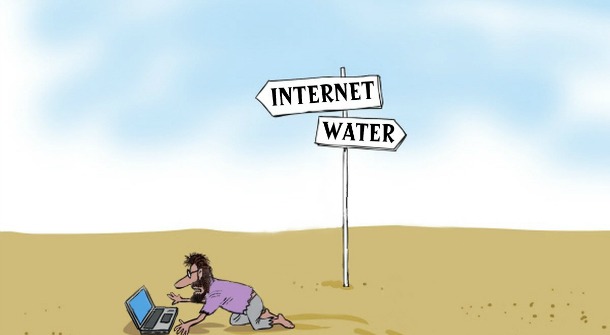

The National Education Policy 2020 has a section called Equitable and Inclusive Education: Learning for All (Section 6). It is important how policy takes into account the different realities of a woman or a girl. The NPE also mentions goals of education. The very first goal is to achieve social justice and equality through an inclusive and equitable education. Second policy talks about in section 6.1 “The goal is to benefit all of India’s children so that no child loses any opportunity to learn and excel because of the circumstances of birth or background” (NPE, 2020). Here the aim of the policy is to provide benefits to all the children of the Indian nation. The aim is universal and uniform. It definitely considers the social background of the individual and prejudice and biases but assures the same kind of opportunity because the lack in education due to biases and prejudice on the basis of gender, caste and religion is holding the nation back from growth, innovation, and progress. Here I want to recall what I have mentioned earlier, girlhood is different from an ideal childhood and the very first step should be to consider this. In addition to that in section 6.2 policy includes women, transgender, SC/ST/OBC, learning abilities, urban poor in one group called Under Represented Category. Policy accepts that despite steady progress due to efforts taken by Indian education system and successive government policies, large disparities still remain at secondary level especially in underrepresented groups. One can assume a possible decline in girls from a particular socio-economic background with religious and caste identities. It is important to identify what are the reasons due to which the girls could not enter the school or they stop going. There are financial constraints, poverty and inaccessibility, lack of financial resources in a family. It all directly affects the education of girls in the family. Let us discuss some major reasons in this section. First is the boundary a girl sees around herself in terms of space and time. How far is the school and in what locality? What is the geographical location of the school? What are the timings? It all impacts the mobility of a girl. It restricts and sets limits. It applies differently for different identities. Parents are concerned with girls’ sexualities when they cross the boundaries of the village. It is not only a gender issue it is a caste issue because the regulation of women’s sexualities is intertwined with the maintenance of caste order. For a Dalit girl it is about belongingness, attending a school but face gender-streaming. We can not deny the reproduction of untouchability in the formal education system. Through visible identities Dalit girl face ill treatment by the more privilege upper caste students as well as the only adult, teacher. The drop outs are also perpetuated through various interlocking systems of power that are based on hierarchies of gender, caste, religion. Zoya Hasan interviewed Muslim women and girls and the sharing from the past were experiences of pain, suppression and oppression. In contemporary India there are various factors acting at multiple levels. There are social norms such as early marriage, managing household and restrictions from family.

In most of the sections (6.3-6.8) policy talks about providing scholarships, incentives to parents and children, providing transport to motivate and enhance the participation of UGRs. To ensure the safety of girls there is a provision of bicycles and group walks. To provide academic support there is peer tutoring, open schooling and councilors. A gender inclusion funds to provide a quality and equitable education for girls which include provision of sanitation, appropriate infrastructure. The larger focus or aim here is to provide access to students coming from UGRs. The problem identified by state is that school is not reaching to the public and the solution is to provide materialistic aids. It seems like policy assumes that gender relations and oppressive structures are same and uniform for everyone and completely depends on the accessibility. Hence there are aspects which policy overlooks. Who are these peers who will help the students in need? One cannot ignore the hierarchies in a classroom on the basis of intellectual capabilities. What about the teacher’s conception about the education of children’s ability dependent on their social background. To identify who needs help in class can also act as marking, discrimination, labeling, leading in segregation. What is required here to focus upon individual ability and to imbibe an engagement with respect. Promoting open schooling has its own disadvantages. Zoya Hasan (2008) shares that girls are more likely to step out of the school to accompany their parents in family earnings. Sometimes they work at home on farms and sometimes outside the house as laborers. Open schooling will allow them to continue doing work and it might push them to drop out.

The next aspect which policy talks about is recognizing women as a significant social asset who needs quality education for a better present and future generation. It ignores the struggles, pain and violence faced by women in the past. There is physical violence and psycho-emotional violence which women face and bear in daily lives. At schools girls face symbolic violence and epistemic violence. These are violence of knowledge and violence through knowledge. Many times we hear that girls are not good at mathematics and science. It is corrosive and harmful and it is deeply permeated which affects the voice and choice by instilling a sense of inferiority and insecurity. There is no mention of the daily accounts of the women or girls who face this at different institutions. How to equip the teachers to handle such situations is not mentioned or suggested in the document. How can we assure a better present if we are not talking or helping to heal the past and for that matter it is not so much in the past. The teacher-student interactions and relationship is a significant aspect to look into. There is no active participation, no reciprocity, lack of dialogue with students, which is like the banking concept of education by Friere where the teacher is only pouring all the knowledge in an empty vessel like students. In result girls from Dalit background feel scared to voice the questions. All these reasons play an active role for a larger dropout rate.

In the last two sections policy proposes a change in school culture and enables a sensitive environment to develop the notions of inclusion and equity. It also mentions a change in school curriculum focusing respect for all, empathy, tolerance, inclusion and equity. One should ask questions: what is policy doing to empower girls against social norms? We require psychosocial skills to effectively deal with demands and challenges of everyday life. It is also important to note that the requirement of these skills and the curriculum could be different for every individual. Next there should be plans to engage with other sex in the schools via curriculum. Adding on to that the policy does not hold governance and community structures accountable in keeping public spaces safe for all castes, nor does it create opportunities for any change in gender norm. It is important to involve parents in interactions with them regarding the specific needs of their child. Many times mothers want their girls to continue going to schools but they are not the ones who make decisions at home.

If we talk about girls’ education there are contests at work. There are social groups i.e. caste, class and religion. There is a binary of male and female. It becomes important that a National Policy of Education incorporate them and plan a framework to consider and represent different social groups. The complete policy takes an economist and liberal stand by assuming that if school and education is accessible girls would not marry early and they would have increased opportunities for future work and education. It ignores how caste and religion relations affect girls’ engagement with the policy.

Isha Anand completed her Post Graduation in Education from Ambedkar University, Delhi.