Charity begins at home, so does activism and the learning/conditioning that calls for activism. These were my first thoughts as I finished watching a 90 minutes long panel discussion hosted by one of the most honest journalists of our times. I refrain from watching news these days and have consciously uninstalled Facebook from my phone. But this panel discussion was not like the ones you see on news channels wherein the question is repeated a hundred times in hundred different tones with an intent to intimidate the speakers and people only bark at each other with nobody willing to listen. This discussion was an attempt to ensure that the space is appropriated by the ones with the lived experiences of what they are talking about. Consequently, there were three Dalit women speaking for more than an hour about how their caste played a role in shaping their lives, how they can only speak for themselves and not for other women in their community because they cannot possibly understand what these women go through- a reminder for all of us that we need to shut our mouths, open our ears and our hearts and truly listen if we genuinely wish to understand what is happening to different people in our own society. We ought to read more and more, observe the different movements taking place and engage in genuine dialogue with people around us. We need to pass the microphone on and let different people appropriate the place meant for them. But most importantly, we ought to acknowledge the privileges we carry right from the time we are born because of the family we are born into.

The virtual space was hosted by journalist Faye D’Souza and the panel included Dalit rights activists, journalists and scholars among others. The discussion went on for almost 90 minutes wherein they shared how they lived their caste in different aspects of their life. While listening to them I couldn’t help but recall my childhood memories as a person growing up on the other side of the fence. This article is an attempt to share how I developed my understanding of caste even before the word was formally introduced to me. It’s a reflection of how different social institutions including my own family (immediate and extended), my community and school reinforced the idea of the ‘other’. It’s an invitation for the readers to pause, think and reflect how knowingly or unknowingly we are still practicing what has been abolished by our constitution. Finally, it’s a reminder that law can only dictate what is right or wrong but the change begins and ends with a shift in our mindsets.

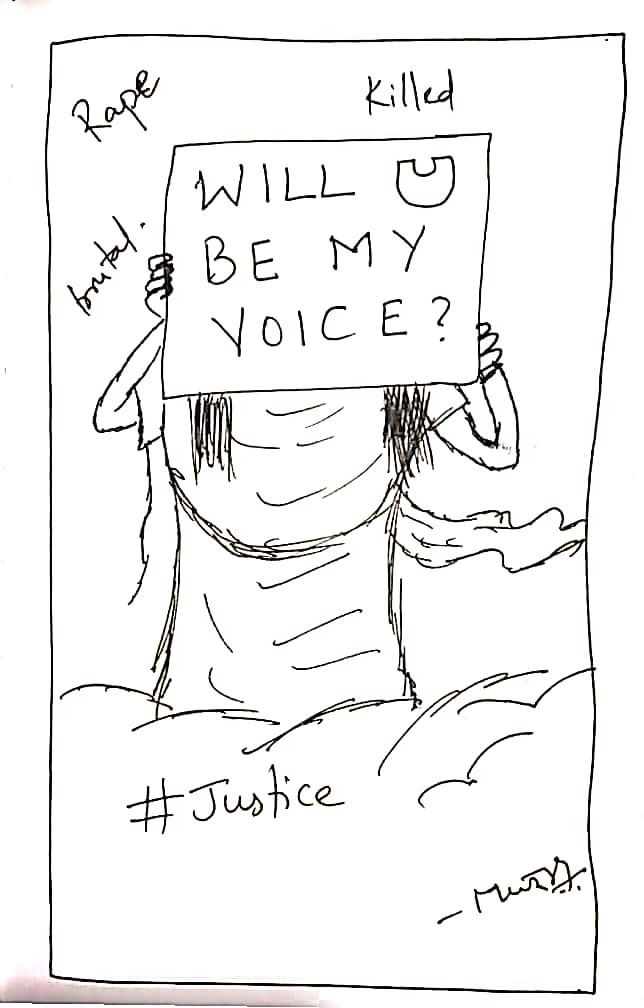

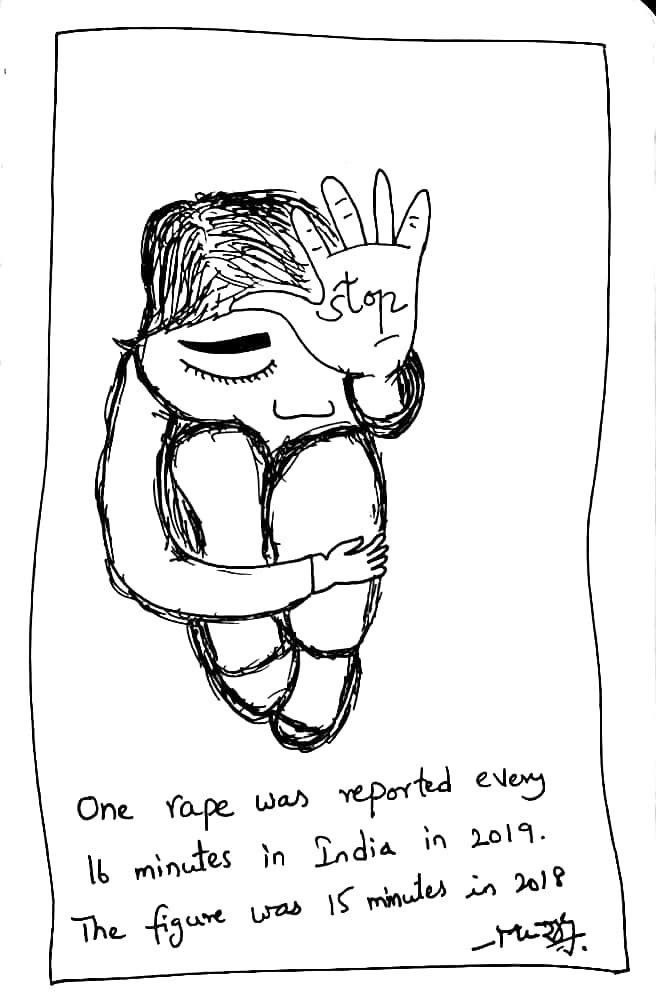

Born in the capital of the country in the year 1993, I belong to an upper caste Hindu family- a Brahmin family. I grew up hearing this often that we are “ucchh koti ke brahman, we are naulakhiya brahmin” something that didn’t really make sense to me but I knew that it was something to be proud of. I remember the different ways in which this Brahminical pride was constantly reinforced over the years- overtly or covertly. And different forces around me- starting from my family to the school I went to and the books I read- played a role in shaping an identity that I didn’t have to spell out as my demeanour, my confidence did that for me whenever I spoke. While I have had my own challenges being a girl starting from being groped in the bus to a constant fear of facing something much worse, I can never imagine going through what happened with a 19 year old in Hathras. It would be unfair to call her a victim of men’s atrocities when she was actually betrayed by the system. I can say for certainty that no policemen can get away with burning my body on record and that confidence I have attained with no cost paid- this is what one’s caste brings with it. Sure I might become a victim due to lack of financial capital but I will have my social capital to compensate for it. Hence, the need for this open-discussion.

What’s there in the Surname? Everything.

The surname I carry explains who I am and in most cases how I am “socially”. I starkly remember one particular conversation that I had a long time back with my cousin about surnames. I was a school going teenager and was writing my name on a notebook. I had only written my first name when she asked why I was not writing my full name. Then she told me that the only people who don’t write their surnames are those who are from the lower castes. I didn’t understand the gravity of the situation back then and I am sure nor did she. She was certainly not a casteist person- definitely not consciously- because she had friends from all backgrounds. As we grew older I saw her openly engage in arguments around casteism in the family discussions. But

this incidence somehow came back to me today when I watched that panel discussion probably because I happened to read several papers around casteism in India and how it operates in different forms- one of them being people hiding their surnames or using surnames like Kumar or Verma to avoid the question around their caste.

A similar incident happened when I was in grade X or XII and my school principal came to our classroom to bless us for our board exams. All of a sudden she asked if anyone of us knew our Gotra. (A Gotra is a Hindu clan tracing its paternal lineage from a common ancestor, usually a saint or sage.) Strangely, or not, I was the only one in that class of forty people who knew my gotra and was appreciated for knowing that. Later, we received a lesson on the importance of knowing our gotra- something I haven’t really used anywhere in my life like most of the other things I learnt there. This should not come as a surprise that I had no friends from the lower caste while growing up. I wouldn’t say it was a conscious choice as I barely had five or six friends in school but somehow I cannot deny the possibility of it being a subconscious decision either.

Children’s literature and media: The subtext offers more than the text

I was always fond of reading and I remember reading stories in panchatantra some of which started as “Ek baar ki baat hai. Ek garib brahmin parivar..”. I never really understood the invisible riches a family could possess that couldn’t be seen in the form of tangible assets. For instance, that Brahmin character would never do menial jobs like cleaning drains or removing animal carcasses to survive. He would rather die of hunger and strangely enough that situation wouldn’t arrive. Some or the other member from the community would come to his rescue because he’s a Brahmin- a devta admi. It’s strange how I read so many stories but it took me all this while to read between the lines.

For the longest time while growing up I believed that words like “choodha, chamar, bhangi” are abuses or slangs. It was much later that I understood that they are particular castes. Interestingly, I never saw my own surname being used without a “ji” as a suffix attached with it. I remember I used to watch a show on Doordarshan in which a character (a peon in a government office) used to emphasize being called as “Pandey Ji, and not Pandey”. What appeared humourous back then makes more sense now. Our class and our caste are two very different aspects of our realities. While we can try to change the former, changing the latter is not possible.

Always Respect Your Elders, But Pay Attention to ‘Conditions Apply’

I remember how caste played out in our home on a daily basis. As a child I was taught that one should always touch the feet of the elders to seek blessings. But such a rule was not to be applied without conditions.

I was often called out and given additional instructions that “we” are not supposed to touch every one’s feet. Strangely enough sometimes the guests used to stop me midway for trying to touch their feet- since they were also part of the same community and knew the caste dynamic at play. Now, this used to happen not just in my maternal grandmother’s house located in a village in Uttarakhand but also in my paternal house in the capital of the country. The difference was that in the village I saw people sitting at a lower position and at a physical distance from my family members but in cities the distance was mostly social and got reflected in a general demeanour and hesitation with which people interacted and was constantly reminded that “we” can only marry in another Brahmin family.

It might be interesting for some people that even within Brahmins I could marry only certain kinds of Brahmins and that was an understanding I had even as a child. I just found these absurd but never really questioned them for logic because you know good children are obedient and never question the elders. The practices like separate utensils for maids or workers were “normal” for our families. When I was an adolescent, my grandmother used to tell us very strictly as to which houses to go to in order to fetch little girls for kanya pujan and which houses to not go to.

I didn’t know that Brahmins had Brahmin Gods only and used to have heated arguments during festive seasons till I grew up to learn the heavy words like conditioning, oppression, endogamy and hegemony.

Choose Your Teachers, Choose Your Lessons.

But it was also in my family that I learnt to respect people for who they are. I was fortunate to spend most of my time with my uncle who had read about Gandhi and Ambedkar and interactions with him helped me look at the world differently. I was mostly his shadow and I realized it when I started getting scolded for arguing with elders and questioning the “normal”. My intent to write this is not to demean my family or any other family of what they believe in. In fact, if anyone feels disrespected that would mean this piece has some truth in it. What I experienced is what every child in families like mine experiences while growing up. I was just fortunate enough to read more than many can. I was fortunate to receive liberal education amongst people from different backgrounds.

And hence I write this today to express my gratitude towards people who encouraged me to question my own beliefs. I also write this to invite people from my generation to observe the “normal” around them and wholeheartedly question it. I wished we had a common school system where children from different backgrounds would sit together and learn about their lived experiences but that’s not a possibility now. But having a genuine dialogue about these realities with one’s family, elderlies and children alike, is certainly doable. Encouraging children to read different stories and mingle with different people is still probable.

And lastly identifying and acknowledging one’s privileges is definitely possible. While I support the ongoing movement for justice for women subjected to caste atrocities, I firmly believe that for India to become an equitable society the privileged group has to consciously step down from their privileged positions to open their ears, minds, hearts and listen.

Richa Pandey is a postgraduate in Education from Azim Premji University.