At a time when our public universities are in turmoil it is important to reflect on the implications of politics, ethics and studentship.

A question that is often asked is whether students should be involved in politics, or whether their primary function is to concentrate only on their studies and think of their future projects—academic accomplishment, career and professional success. Yes, there are people who do not like students to be involved in politics which, they fear, pollutes and disturbs the academic culture of our universities. Possibly there are two reasons for this apprehension which need to be contextualized and understood. First, in our times characterized by the bankruptcy of the political class and widespread disillusionment because of scams, corruption and broken promises, the word ‘politics’ itself has acquired a negative connotation. Seldom does it invoke the memories of Bhagat Singh and Gandhi, or the historic role of universities in the freedom struggle. Instead, in the age of ‘legitimation crisis’ politics is seen to be immoral—an act devoid of illuminating thoughts and practices. And there is no doubt that this negative politics does characterize many of our colleges and universities; we witness the same ‘party politics’ with its divisive factionalism, caste/communal identities, regionalism and violence. This politics, even an otherwise sensitive/politically conscious person would not hesitate to say, does by no means enrich the ethos of studentship or culture of learning. Second, for the aspiring middle class—particularly, in the neo-liberal era—the purpose of education has acquired a dramatic transformation. Education is seen to be purely utilitarian—learning a ‘skill’, possessing a degree, achieving ‘excellence’ and getting a job. This one-dimensional approach to education (which has been further activated because of the destiny of a Third World country like ours with its flawed political economy and structural unevenness leading to scarcity of resources and survival anxiety) does not wish to entertain any other ‘disturbance’—ideological struggles, political resistance and concern with larger social issues. No wonder, the idea of a clean/hygienic/ union free campus promoting the idea of ‘meritocracy’ and the survival of the fittest has its appeal, and it is seen to be refreshingly different from ‘politically disturbed’ campuses of public universities. Are private universities and all sorts of institutes of technology and management in tune with this middle class aspiration in the age of neoliberalism?

(I)

Politics can be different

However, the debate does not end here. Because politics is not and should not be merely ‘party politics’—the politics of numbers, the strategy for winning elections, the manipulative act without solid ethical/moral foundations. At a deeper level, politics has a different meaning. It is a critical/communicative engagement with the question of power in society—how it is shared or possessed, disseminated or exercised; or how we think of and implement the project of collective welfare; our orientation to natural resources, people’s knowledge and skills; and the way we look at science, technology and culture. In other words, politics can also be seen as a delicate art of collective living and using power—meaningfully and gracefully. No wonder, the domain of politics is filled with contesting ideologies, perspectives and associated moral principles. It is in this sense that every act is ‘political’. For instance, if I chose to use bicycle, and plead for the reduction of the use of cars, I am engaged in a political act. I may not contest the elections; I may not be a member of a political party; but my act is an intervention, it is a voice of dissent against a policy that promotes car companies, makes cities polluted, and reproduces social inequality. Likewise, even if a typical management student from a reputed business school feels that he doesn’t do politics and concentrates only on his studies and career, the fact is that his action has political implications. Because through his so called ‘non-political’ act he is actually giving his consent to certain kind of politics of knowledge—knowledge is for ‘meritocracy’, knowledge is for the promotion of corporate interests! That is why, as it is said, nothing is free from politics because every act of ours is contributing in its own way to the debate on the practice of power in society. If politics is all-pervading, can students be free from it? Certainly not. But then, there can be different practices of politics. If you strive for a just society free from the principles of domination, violence and inequality, your politics ought to have strong ethical foundations; it ought to reconcile personal integrity and ideological practice in the public domain. For instance, if I fight against corporate capitalism, it is important for me to move towards a lifestyle that is reasonably free from its rationale —its principle of profit, depletion of natural resources and reckless consumption. And there is no contradiction between the politics of this kind and the ethos of studentship or academic life.

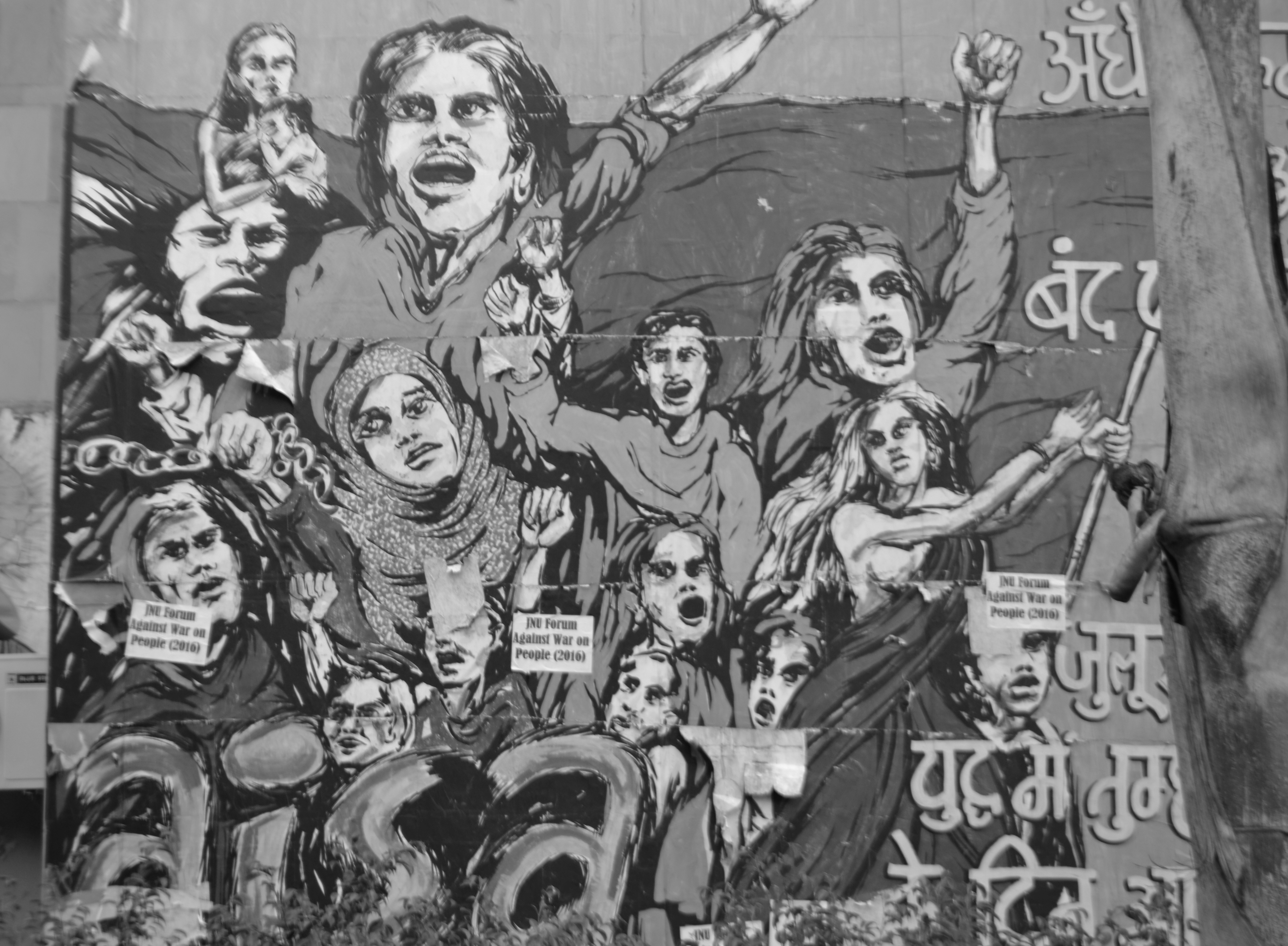

It is in this context that we can see the relationship between academic pursuits—say, in liberal arts and social sciences—and political philosophies and practices. Take, for instance, the enormous amount of literature on gender, caste and social exclusion which students in good public universities study; now this academic engagement itself is prone to the practice of some kind of politics—the politics that fights patriarchy and strives for women’s rights; the politics that invokes the likes of Phule and Ambedkar, and fights caste discrimination and social exclusion; the politics that raises its voice of dissent against global capitalism and marginalization of people. No wonder, Marxism, Feminism, Ambedkarism—the influence of these ideologies is felt amongst a significant section of students (remember, the social composition if students is changing; more and more students are coming from the marginalized sections with aspirations for dignity and justice) in these public universities. Why should we think that it is bad? Instead, it activates academic life, and establishes an organic relationship between politics and philosophy, theory and practice. It is, however, a different story that the ruling establishment (guided by neo-liberalism and social conservatism) remains suspicious of this politics, and targets these ‘disturbed’ campuses. As a matter of fact, there is no branch of knowledge without politico-ethical implications. It is a myth that science or engineering is apolitical. How can a student escape the question relating to the practice and use of science? Should science or technology be used for a model of ‘development’ that causes ecological disaster, privileges the rich and marginalizes the poor, or should it be used for people, for the enrichment of their living and consciousness? If a student of science or technology doesn’t bother about these questions in the name of ‘value-neutrality’, he/she is essentially giving his/her consent to the status quo. When science and socio-political conservatism go together, the result is disastrous. Hence meaningful education, be it of science or humanities, and ethical politics for the pursuit of an egalitarian society need not be seen as contradictory.

(II)

Pragmatism and its temptations

Yet, not everything happens in a way one desires. Even the kind of sane politics we are talking about finds obstacles, or temptations to get diverted; it is not easy to retain sanity and moral foundations. There are three points that need to be talked about. First, in the academic life there is a tendency to become reductionist, and this leads to intolerance and resultant violence. For instance, it is not uncommon to see the Marxists in the campus refusing to engage meaningfully with non-Marxists; or Ambedkarites unwilling to hear anything good about Gandhi. This causes severe damage to the dialogic spirit of learning or a dignified mode of resistance or living with differences. As a result, all sorts of violence—physical or symbolic—begin to pollute the political milieu. Second, the mainstream political parties with their mega ambitions tempt and use students; and as a result, the campus politics tends to lose its uniqueness and distinctive style, and we witness the same rhetoric, the same ideological baggage, the same manipulative strategy. How often the mainstream political parties (left or right) are allowed to hijack the campus issue! Well, the university is not an insulated island, and students do have their opinions on political parties. But only through relative autonomy can the students retain the distinctiveness of their politico-academic engagement. It is really sad when a student leader repeats what the High Command or the Politburo wants him to do. It has its negative consequences. Third, when politics loses its dialogic character, the beauty of studentship declines. What is studentship? It is the curiosity to learn, to wonder, to explore; it is a spirit of communion with teachers; it is the ability to cultivate the qualities like love, empathy and reverence. But it is sad that politics—even the supposedly radical politics— tends to destroy these qualities of studentship. It breeds the arrogance of ‘certainty’ rather than the humility of a seeker. I may be a Marxist, and my teacher may be an idealist philosopher. It is important for me to engage with him with a spirit of respect and critical enquiry, with an open mind, a mind that is ready to be surprised, ready to learn and unlearn. My vice-chancellor is also my teacher. Even when I oppose some administrative policies, I should not degenerate myself into an abuser. When it happens slogans and stereotypes become more important than the philosophic substance. Learning stops; rhetoric begins. Politics without grace, politics without civility, politics without the spirit of a determined, yet humble learner—it is not what we want. It is really sad that even in some leading universities known for their academic culture, the quality of politics has deteriorated.

We are passing through difficult times. An average college/university in the country is a site of cultural and political decay. With demotivated students and teachers, with the culture of guide books, exam-centric learning and mass copying, and with violent politics (caste/communal sentiments, repeated gherao of vice-chancellors and administrators, destruction of university properties, and clash with the cops) these places fail to arouse hope. Again, we have private universities and elite institutions that tend to transform the youth into one-dimensional careerists utterly indifferent to the larger social issues. Here the ‘absence of politics’ means another politics—the politics that sanctifies the status quo, the neo-liberal mantra of an atomized individual obsessed with his own ‘success’. Furthermore, the rapidly growing culture industry with its bombardment of images tends to negate the spirit of critical thinking; gadgets and technological miracles seek to possess and paralyze the individual; alcoholism, addiction, sexual imageries and fantasies cause psychic bewilderment. At this juncture, the question arises: Is it possible for young students to imagine and strive for yet another world? Yes, it requires politics, but not the kind of politics we are used to. Politics liberates if it is ethical and dialogic, if it is meditation—one’s true religiosity.

Can our universities give birth to such politics? We pose the debate, and request our readers to respond to it.

This article is published in The New Leam, JULY Issue( Vol.2 No.13) and available in print version.

To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com Or visit FlipKart.com

You Liked the article? We’re a non-profit. Support This Endeavour – http://thenewleam.com/?page_id=964