The judges of normality are everywhere. We are in the society of the teacher-judge, the doctor-judge, the educator-judge, the ‘social-worker’ judge; it is on them that the universal reign of the normative is based; and each individual, wherever he may find himself, subjects to it his body, his gestures, his behaviour, his achievements. The carceral network, in its compact or disseminated forms, with its systems of insertion, distribution, surveillance, observation, has been the greatest support, in modern society, of the normalising power.

– Michel Foucault

When I came to know about Whats App’s admission that journalists and human rights activists in India who are its users had been targets of surveillance by operators using Israeli spyware Pegasus, I was disturbed, but not surprised. I was disturbed because it reminded me once again of the times we live in–when with the ever-expanding new technologies of surveillance (much ahead of what Foucault wrote in his classic text Discipline and Punish), the act of spying acquires a new dimension, and allows the perpetuators of totalitarian politics to establish constant visibility over the dissenters.

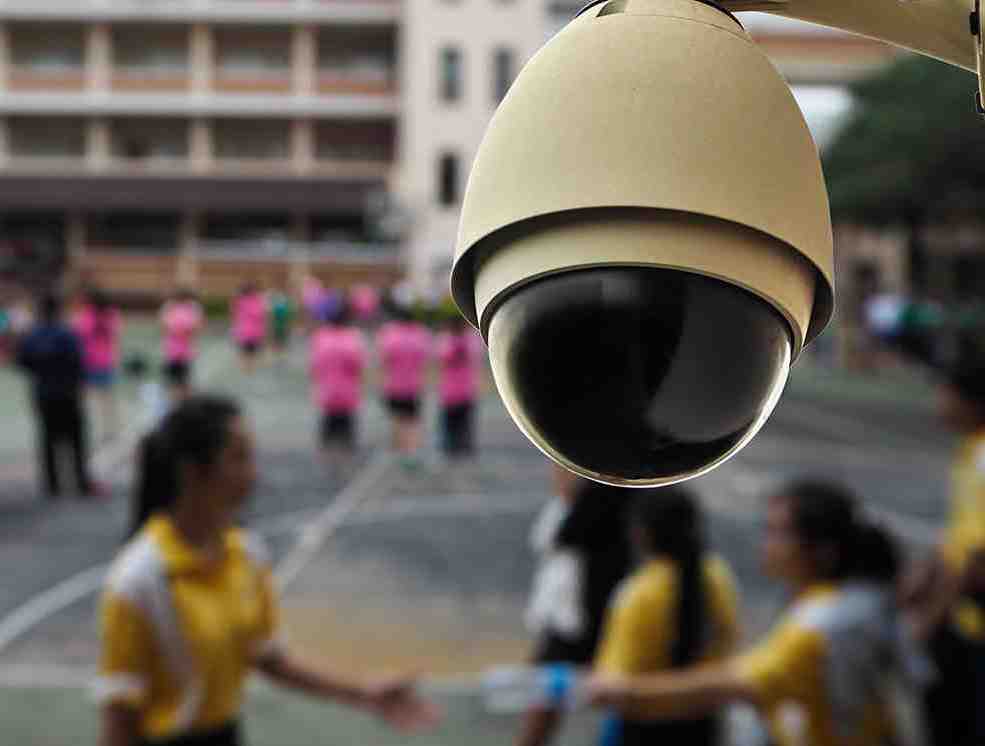

A technologically developed modern society need not necessarily promote the spirit of freedom and democracy; instead, it can intensify the militaristic dream of a controlled system. This realization of the crisis of modernity as well as democracy was disturbing. But then, I was not surprised because somehow we have become used to the culture of spying and surveillance. “You are under CCTV camera surveillance”: when our everyday existence is based on this technique of ‘discipline’, why should one be surprised if the centre of power wants to know every minute detail about the thoughts and deeds of the dissenters?

We: The Carriers of Surveillance

What is really frightening is that it is not merely about the repressive apparatus of the state; in fact, we breathe it, and accept its inevitability and even desirability. Paradoxically, what is repressive has become an object of love: a guide book for a ‘perfectly disciplined’ society. We are monitored; and at the same time, we love to monitor others. In other words, we ourselves are the carriers of surveillance. We have begun to believe that surveillance is good and desirable for our own safety. It is not merely the logic of the techno-bureaucratic nation- state; we seem to have given our consent to it.

And hence, it does not hurt us anymore when at airports and railway stations the cops with the gaze of suspicion touch every part of our bodies, scrutinize us thoroughly, and eventually confirm that we are not ‘terrorists’ or ‘criminals’. And this logic of ‘safety’ is infectious; it crosses all boundaries. Hence, we have allowed ourselves to live amid the all-pervading presence of CCTV cameras. The eyes that observe without being observed are everywhere: at schools, classrooms, washrooms, elevators, shops, housing societies, and even our children’s rooms. In fact, we want more and more surveillance because we have begun to believe that only with this meticulous process of monitoring our gestures and behaviours, we can be controlled and disciplined, or to use Michel Foucault’s words, ‘hierarchized, reformed and normalized’.

No, I am not a romantic fool. The practice of surveillance in some form or other was always prevalent; and it is not something unique to our times. I also know that we do not necessarily live amid saints and noble souls; and yes, negative/destructive impulses do exist within us, and the Hobbesian problem of ‘order’ continues to haunt us. Hence, as it would be said, it is always desirable to be alert and cautious; and society must observe, classify, and document the details of the deviants to discipline and punish, and restore ‘order’.

I also admit that the poetry of inner discipline is not easy to evolve; and many of us would curb our negativeness–at least temporarily– only because we fear that the centre of power is constantly observing us. I know that it is not vey easy to convince one–particularly, in a world characterized by all sorts of conspiracies and violence–say,a terrorist attack in Kashmir, a bomb blast in Guawahati, a suspicious/unidentifiable object found in the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi, or a child murdered in the washroom of a school in Kolkata, that the practice of surveillance is wrong. Let the likes of Orwell and Foucault bother about it. We seem to be quite comfortable with it.

More Surveillance, More Violence

Yet, I wish to make three points in order to evolve my critique of the logic of surveillance. To begin with, It has severely affected the way we look at ourselves. As the surveillance machinery makes us believe that we are all potential terrorists, rapists, murdererers or thieves, we too have begun to look at one another through this perception. When I walk through the Janpath market, and the cops constantly announce that I have to be perpetually alert because there might be a terrorist or a thief around, I find myself amid the vicious circle of collective doubt and suspicion. It is not just my privilege to suspect others; I too am being suspected.

Yes, the psychology of doubt and suspicion seems to have become the new normal. And this is terribly dangerous; we lose the spirit of trust: the cementing force of any civilization. Once trust disappears, and surveillance is normalized, we lose our humanity: our spontaneity, our simple faith that not everyone in the world does necessarily have bad intentions. In other words, we begin to decay from inside. Relationships crumble; anonymity is intensified; fear spreads As a result, with surveillance, society becomes more toxic and violent.

Second, with our obsessive indulgence with technology, we seem to have voluntarily given our consent to the culture of surveillance. When it is said that they know everything about us, it is equally true that we too are over- enthusiastic to make our private lives accessible to a wider public–Whats App groups and Facebook/Instagram friends and followers. The dresses we wear, the new gadgets we have purchased, the wedding parties we have attended, the restaurants we have visited, and even our intimate moments with the loved ones: everything is now a public document.

Is it the reason that only in our times a television serial like Bigg Boss can become popular? Yes, on the television screen we see a group of ‘celebrities’–confined to an insulated zone– cracking jokes, conspiring, fighting, eating, laughing, loving; and we derive some sort of pleasure out of this gaze. Likewise, through Facebook/Instagram/Whats App we too are playing the same game, although, unlike the participants in the Bigg Boss, we are not paid.

Third, with some sort of techno-hallucination we have begun to believe that there is no other way to ‘civilize’ us except the psychology of fear that the surveillance machinery generates. While our employers believe that without the bio-metric, we would escape from our assigned works; school Principals trust the eyes of the CCTV camera more than the ability of a dialogic teacher to deal with children with the ethics of love and care. Whereas we are required to carry our Aadhaar and PAN cards always with us to prove our legitimate existence, we erect more and more walls of separation.

If the management of a residential society keeps security guards at the entry gate, and instructs them to interrogate thoroughly every visitor with a suspicious look of objectification, it is not surprising that that we have already internalized the logic of the NRC. Hence, we think that we need not work on ourselves–the way, say, Jesus wanted us to spread the religiosity of love and compassion, Marx wanted us to overcome the logic of exploitation, and move towards the communism of free souls, or Gandhi urged us to reconcile inner freedom and moral responsibility.

Instead, we would argue that technology–particularly, the technology of surveillance–is the ultimate solution. Hence, we would not try to understand why a young boy becomes a ‘suicide bomber’ and plays with death; instead, with the militaristic dream of ‘normalcy’, we would suspect, or establish our visibility over every young person in the ‘disturbed’ territority. In the name of eliminating violence, we would generate more violence. Because we would hardly bother to alter what promotes the epidemic of disruptive behaviour: the structural violence implicit in the asymmetrical distribution of material wealth and cultural resources, and the all-pervading alienated existence devoid of a deeper meaning and purpose.

Is it the fate of modernity? Is it what we call progress? Is it that we have never realized the spirit of freedom–the freedom to love, share and care, and only understood the language of fear, conspiracy and surveillance?

Avijit Pathak is Professor of Sociology at JNU