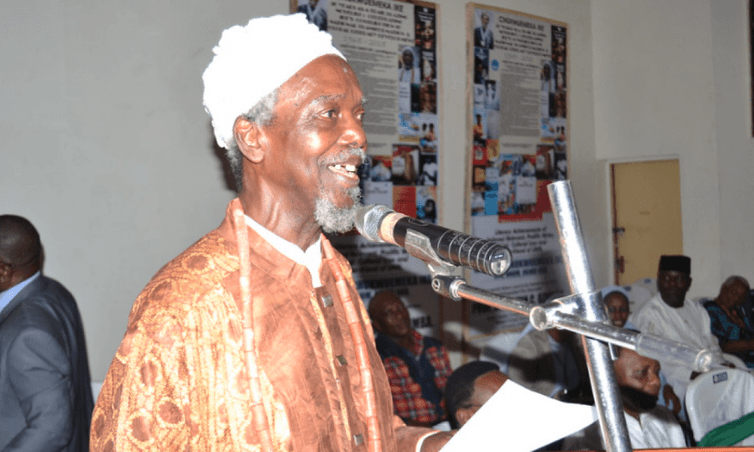

Chukwuemeka Ike is a giant whose accomplishments are as numerous as his stature is tall. Born on 28th April 1931 into the royal family of Ndikelionwu in eastern Nigeria, Ike was one of the early adopters of Western education among his people. He attended renowned Nigerian elite schools, Government College Umuahia and the University of Ibadan.

Schooling alongside other great writers including Chinua Achebe and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, Ike towered as a literary icon. His literary works, which span every aspect of human life, remain relevant through time.

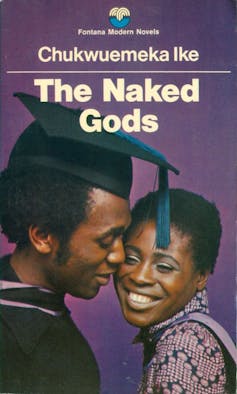

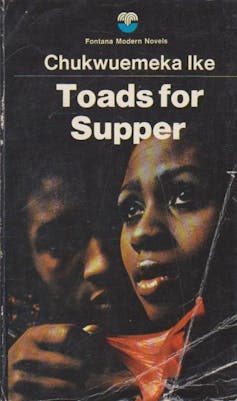

Ike’s works include Toads for Supper (1965), The Naked Gods (1970), The Potter’s Wheel (1973), Sunset at Dawn (1976) Expo ‘77 (1980), The Chicken Chasers, The Bottled Leopard (1985), Our Children Are Coming (1990), The Search (1991), Conspiracy of Silence (2001), Toads for Ever (2007). Through the pages of these works Ike sends a singular message to the world: unity in diversity.

A personal connection

I had read Ike’s The Bottled Leopard in secondary school, but I felt special bonding with him in 2015. The University of Nigeria, Nsukka, had hosted a panel discussion to mark the 50th anniversary of his magnum opus, Toads for Supper.

I was part of the four-man panel that also featured Onuora Nzekwu – the author of the famous Nigerian children novel, Eze Goes to School. Preparing my paper for this event ignited in me a special interest in Ike’s literary world.

After the discussion, Ike shook my hands. He strongly appreciated that I understood the core of his message: border bridging. Border bridging is a concept in Border Studies. The term ‘border’ broadly refers to the differences between places and people. In the absence of tolerance, borders become points of conflicts. To avoid disputes, humans need to bridge our borders. ‘Border bridging’ refers to the tolerance of differences between or among individuals or nations.

Fontana

That panel discussion led to my first publication on Ike titled, ‘Navigating through Impalpable Borders in Chukwuemeka Ike’s Toads for Supper’ – which was published in Okike: An African Journal of New Writing. The publication reinforced my understanding that unguarded social borders create adverse consequences that affect how we relate to each other in our societies.

Borders also formed the core of my doctoral studies completed in 2019. A part of my doctoral thesis, ‘The Politics and Poetics of the Border in Chukwuemeka Ike’s Sunset at Dawn,’ explores Ike’s central argument for borders or social difference to transcend natal belonging.

A legacy of unity in diversity

Ike was a man of deep insight. He always warned against disunity exemplified by the core themes of sociocultural border bridging in Sunset at Dawn, Toads for Supper and The Bottled Leopard; growth and identity reformation in The Potter’s Wheel; and individual recognition and social inclusivity in Our Children are Coming. His two major characters in Toads for Supper (Amadi and Aduke) are symbolic of the detrimental effect of ethnic fanaticism.

Lovers Amadi and Aduke were respectively members of Igbo and Yoruba ethnic groups in Nigeria. Conflicts between ethnic groups have remained common especially since the 1967 Nigerian-Biafran civil war. Thus, Amadi and Aduke faced discouragement by family members and society, as they tried to get married to each other. The negative influence led to their psychological breakdown, showing the harm of ethnicism.

Fontana

In his personal life, Ike also bridged borders by marrying Adebimpe Olurinsola Ike, a Yoruba woman.

Ike’s legacy is further exemplified in his war novel, Sunset at Dawn. Despite experiencing the brutality of the Nigerian-Biafran civil war and its devastating effect on the then Biafrans, he neutrally captured the negative effects of ethnic fanaticism. Sunset at Dawn is part of a few fiction books on Nigerian-Biafran war that paints a neutral picture of the civil war. It indicted both warring factions as casualties. The lives of Fatima and Halima – both Northern characters – expose the need for humans to let go of an attachment to their place of birth. Fatima and Halima embody cultural border bridging by embracing the Biafrans and finding home in a new space.

An ever-green impact

Ike’s voice continues to ring his legacy in the world especially in this era of increasing ‘other-rebellion’ that exists in the forms of xenophobia, insurgency, terrorism and global-green crisis. These messages, as well as the peaceful, philanthropic life he led, will keep on portraying him as a strong believer in common humanity.

He believed that we should all build and maintain bridges that connect the human person to the other (no matter what this ‘other’ implies). In his life and works, Ike exemplified the possibility of creating a community where everyone lives according to their own rhythm, and yet respects the individual rhythms of others. You can find this in his ability to maintain peace and orderliness throughout his monarchy as the king of Ndikelionwu Kingdom from 2008-2020. No community tension or war was recorded during his reign.

Ike’s death on January 9, 2020 opens another page in the annals of his life. His works live on beyond his time on earth. Everyone who believes in a common humanity should share his message of ubuntu, and unity in diversity. We all must not let him die!![]()

Mary J. N. Okolie, Lecturer, Department of English and Literary Studies, University of Nigeria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.