Rethinking Reading: ICSE and the introduction of popular comics in official Curriculum

Recently ICSE introduced comics like Tintin and Asterix in their syllabus. What will be its consequences for the culture of reading?

By Pooja Bhatia/ The New Leam

If what we read is who we are, I wonder what the children of our times will turn out be. For the Kindle bred generation abhors reading and would rather spend their time and pocket money on movies, gaming, watching TV or net surfing. Kids today have access to a whole range of recreational activities and forms of entertainment than their parents did while growing up in the pre-reforms phase. Reading then has become synonymous with school texts that children feel they are grudgingly made to study to qualify exams. Even mushrooming book fairs and regional lit fests have failed to address the dying reading culture among youngsters and their dwindling interest towards literature.

It is within this context that ICSE’s decision to introduce popular texts like Tintin, Asterix comics, and Harry Potter in its revised curriculum for classes 3-8 has thrown up fresh questions and pedagogic concerns. While parents have welcomed the move in general, some lament the loss/lack of serious reading. Can these new age texts stand up to classical texts like To Kill a Mocking Bird, The Jungle Book, The Little Women, Tom Sawyer, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities in terms of quality and content? While they do fuel the imagination, can they nourish the mind? While some educators feel these texts should be used merely as add-ons, others want it to be a viable alternative to the likes of Shakespeare, Kipling, Keats and Wordsworth that children find difficult to read and comprehend. Another matter of contention is the definition, scope and extent of literature itself. What does literature include and what purpose does it serve? Should vernacular texts translated into English be considered a part of English literature? If yes, then why not expose children from diverse backgrounds to the indigenous writings of Tagore, Premchand, Mahashweta Devi, Omprakash Valmiki, Vijay Tendulkar, Dinkar at a young age? How far can mythical stories from the Panchatantra, Jataka Tales, Ramayana and Mahabharata be incorporated in the syllabus? If fictional characters like Nancy Drew and Sherlock Holmes can find representation in the curriculum, why cannot Indian legends like Tenali Raman, Akbar-Birbal, Vikram-Betal be included to broaden the horizon and experience of reading.

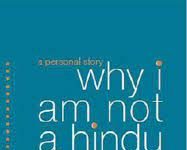

This brings us to eminent educationist Krishna Kumar’s central questions of what to teach and how to teach in a classroom. Krishna Kumar views education as a “gift that adults bestow on children”. Given that metaphor, the gift has to be of the liking of children for it be useful. If a child cannot relate to the gift, no matter how expensive or wonderful, he will find little use for it in his life. Similarly, the content taught in schools has to be relevant to the child’s immediate surroundings for her to decipher its meanings and engage with it. Noted political scientist and activist for Dalit rights, Kancha llaiah elaborates on this point in his book, “Why I am not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy”. He argues that the inimical, external environment of the school alienates children from dalit or tribal backgrounds from the environment of their homes and communities. Since they cannot relate to the brahmanical writings of upper caste poets and writers, they choose to drop out of the formal education system. School which should ideally have been a liberator of those born in misery and drudgery becomes a site of their humiliation and oppression.

The rural-urban divide is another important factor that needs to be taken into consideration while drafting the syllabus for literature. For a child born in a village in Tamil Nadu or Gujarat, the writings of Ruskin Bond may turn out to be as foreign as the writings of J.K.Rowling. At the primary level, vernacular literature drawn from the writings of local authors and legends might prove more successful in sustaining her interest in reading than alien authors imposed from above. While Asterix and Tintin comics hold appeal for an urban bred kid; his rural counterpart might be smitten by the stories of Amar Chitra Katha.

Reading is as much an emotional exercise as it is an intellectual exercise nourishing the soul and mind alike. In “Bookless in Baghdad”, Shashi Tharoor recalls his love of reading as a child and how it kept him in good company during days of sickness and sadness. While his frail body abandoned him, his mind wandered far and away, keeping pace with his books and bringing him comfort. He believes the books he read as a kid have left a formidable impact on his personality and world view. To conclude, I would say, vernacular or foreign, comic or novel, classical or new age; the onus is on us adults to present children a gift not necessarily of their choosing but one that is meaningful and truly joyful.

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.