Millions of working parents have spent months largely trapped in their homes with their children. Many are trying to get their jobs done remotely in the constant presence of their kids, and they are desperate for some peace and quiet.

Many mothers and fathers have sought any available remedy that would enable them to do their jobs and fight cabin fever – including some who have given their children a free pass on video games, social media and television. One survey of more than 3,000 parents found that screen time for their kids had increased by 500% during the pandemic.

Screen time rules

In case you missed it, when the World Health Organization released daily screen time guidelines for children in April 2019, it suggested tight limits.

Infants should get none at all, and kids between the ages of 1 and 5 should spend no more than one hour daily staring at devices. The WHO does not provide specific limits for older children, but some research has suggested that excessive screen time for teenagers could be linked to mental health problems like anxiety and depression.

Kids were already spending far more time than recommended with screens before the pandemic, and had been for years.

As far back as the late 1990s, children between the ages of 3 and 5 years old were averaging two and a half hours per day with their screens. And, naturally, what screen time rules families had been enforcing have been on hold since at least mid-March 2020, when most U.S. communities entered an era of social distancing.

Prone to distraction

Should parents worry if their children are spending more time than ever online to learn, play and while away the hours until they can freely study and socialize again? The short answer is no – as long as they don’t allow pandemic screen time habits to morph into permanent screen time habits.

Shortly before the coronavirus led to schools across the country suspending in-person instruction for safety reasons, I wrapped up my upcoming book on the power of digital devices to distract students from their learning. In “Distracted:

Why Students Can’t Focus and What You Can Do About It,” I argue that trying to eliminate distractions from classroom takes the wrong approach. The human brain is naturally prone to distraction, as scientists and philosophers have been attesting for centuries now.

The problem with distraction in school is not the distractions themselves. Children and adults alike can use social media or view screens in perfectly healthy ways.

The problem occurs when excessive attention to screens crowds out other learning behaviors. A child watching YouTube on her phone in the classroom or during study time is not developing her writing skills or mastering new vocabulary. Teachers should consider how to cultivate better attention to those behaviors, rather than trying to eliminate all distractions.

Likewise, parents should not view screens as the enemy of their children, even if they do need to be wary of the impact of excessive screen time on eye health and how much sleep their kids get.

The trouble with excessive screen time is that it eclipses healthy behaviors that all children need. When children gaze passively at screens, they aren’t exercising, playing with their friends or siblings, or snuggling with their parents during story time.

What I believe parents need to worry about isn’t how much time kids are spending cradling their devices during our current crisis. It’s whether their children are forming habits that will continue after the pandemic’s over. Those habits could stop today’s youngest Americans from resuming healthier and more creative behaviors like reading or imaginative play.

If kids can kick their pandemic screen patterns, and return to the relatively healthier levels of screen time they had before, they will probably be just fine. The human brain is remarkably malleable. It has extraordinary potential to rewire itself in the face of accident or illness and adapt to new circumstances.

Making a habit of bingeing

This feature of the human brain, known as neuroplasticity, is one of the reasons that doctors and health organizations recommend limits to the screen time of young children. Experts, educators and families alike don’t want their brains developing as organs primarily designed for television binge-watching and video game marathons.

In the current moment, parents should be grateful for brain neuroplasticity, and take heart from the fact that whatever changes that might have occurred over the past few months need not be permanent ones. The brain transforms in response to our circumstances and behaviors – and it changes again as those circumstances and behaviors evolve. A few months of excessive screen time won’t override an otherwise healthy childhood of moderate screen time and active play.

The ways in which work and school are adapting to social distancing suggest that screens are not the enemy. Rather, they are enabling people around the world to work and learn and communicate with loved ones during this extraordinary time.

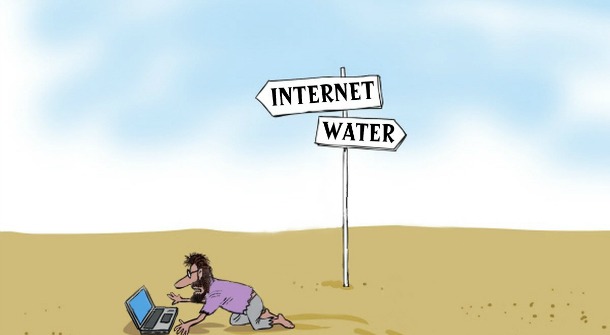

The real enemies of healthy development in children are the same enemies adults face: a sedentary lifestyle, social isolation and distractions from work and learning. Using screens too much can contribute to all of these problems – but they can also counter them.

Researchers point out, after all, that not all screen time is equal. You might not make the same judgment about a child writing a novel using Google Docs, FaceTiming with Grandma or using a smartphone to geocache with their friends.

As restrictions on everyone’s movements and activities evolve in the coming months, parents can support the healthy development of their children by encouraging them to return to such healthy and imaginative behaviors – whether they take place in front of screens or not.![]()

James M. Lang, Professor of English and Director of the Center for Teaching Excellence, Assumption College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.