As a nineteen-year-old undergraduate student in Mumbai, I cannot help but notice a growing disinterest or even rejection of Gandhi among my peers and much of India’s youth. This observation might seem anecdotal or subjective, but the trends I have observed – both in daily interactions as well as on social media, suggest that this is not an isolated phenomenon. It seems that Gandhi’s relevance which was once central to Indian thought, is fading from our collective consciousness.

In trying to understand this shift, I find sociologist Avijit Pathak’s analysis particularly insightful. He identifies four major forces driving what he calls the “Gandhi-bashing industry”:

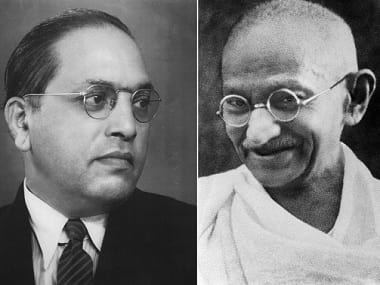

Modernists who dismiss him as non-modern and anti-development; militant cultural nationalists who are threatened by his spirit of collectiveness; reductionist Marxists who favour economic determinism and reject his emphasis on non-violence; and a faction of non-empathetic Ambedkarites who seek to retain the duality of Gandhi versus Ambedkar on the caste issue through an exclusivist approach.

This framework maps the complex intersectionality of ideologies that have shaped public opinion against Gandhi.

The fetish with technocratisation

The fetishisation of technocratic development, which Gandhi saw as a dangerous ideology rather than a tool for progress, plays a significant role in this shift. The state projects seductive visions of a high-tech, hyper-affluent society – one that is eco-friendly, post-human and seemingly ideal. Yet, these development fantasies are smokescreens that conceal the exploitation of nature and labour in service of a narrow elite power group.

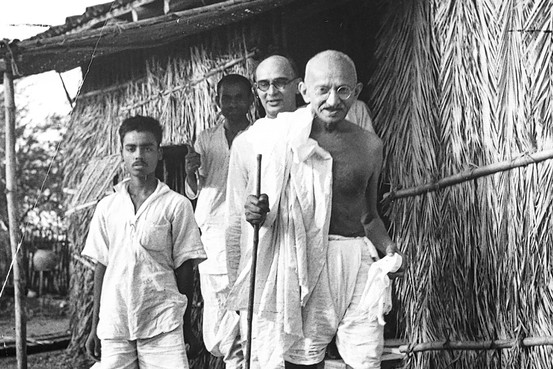

In stark contrast stands Gandhi’s charkha – the humble spinning wheel. It symbolizes a slower, more grounded approach. It is deliberate, rooted in human labour and the rhythms of nature. It is a radical counterpoint to the impersonal and disembodied rush towards unchecked development.

The dismissal of Gandhi is also fuelled by the rising militarization of public discourse, often through religious polarization. Power groups that are eager to control public narratives simultaneously appropriate and negate Gandhi’s legacy.

Gandhi would use powerful symbols like khadi, salt, charkha that were once catalysts for mass movements. But today, they are stripped of their radical essence and reduced to mere commodities.

Stripping Gandhi of the true essenece of his ideas

There is an appropriation of Gandhi’s image in politics. His face is plastered on banners during rallies, the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan was launched on his birthday, and his image is even on our banknotes. This co-opting of Gandhi within the neoliberal marketplace of Indian politics transforms him into what Jean Baudrillard might call a simulacrum – a floating symbol so endlessly circulated that detaches him from what he once represented, and sanitizes his radical politics to make him palatable to the very forces he opposed.

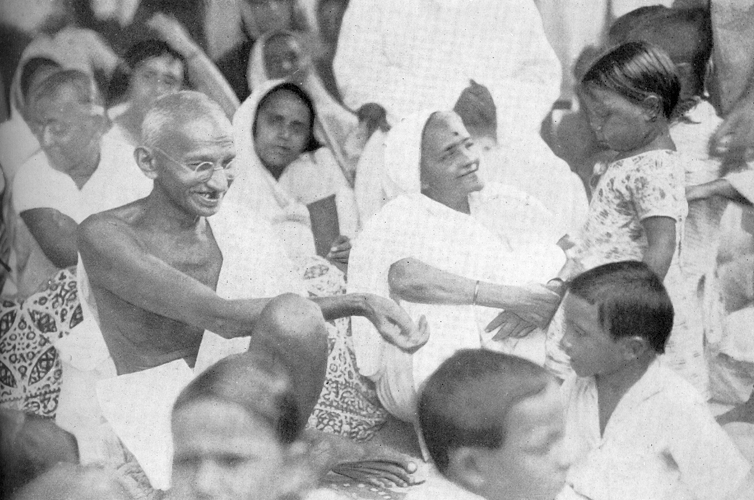

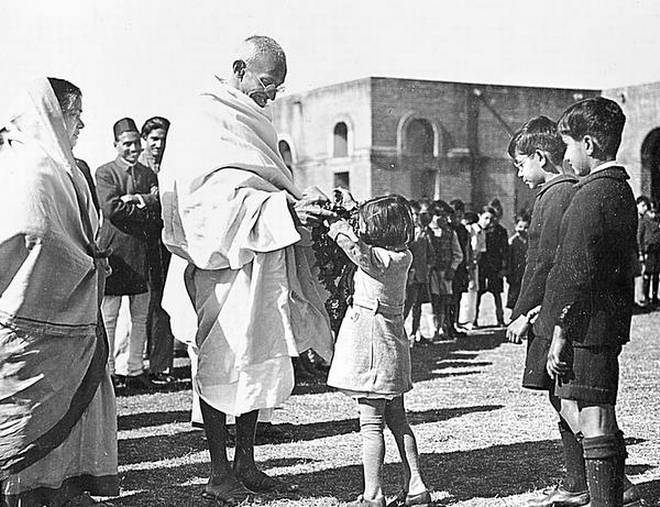

Furthermore, what is even more troubling is the spiritual void deepening in Indian politics today. Gandhi once treated politics as an extension of his spiritual practice, a platform for his sadhana and tested his morality in the crucible of public life. He was an accessible politician who engaged openly with citizens, whether through critique, debate, or conversation.

Today, the public image of power is shaped by narcissistic, non-dialogic displays of authority. Strength is equated with brute force, and in such a worldview, Gandhi’s non-violence is dismissed as weak, irrelevant and cowardly.

Yet, in our violence-plagued world, youth activism still calls for justice and accountability. And engaging with Gandhi’s philosophy in this context can be a courageous act of defiance against the cynicism that threatens to consume us. His emphasis on cultivating a morally and socially responsible world is an inspiration and a blueprint for those seeking to foster a more compassionate society.

Rethinking the overpowering discourse of capitalism and commodity fetish

Gandhi’s legacy also gives us a powerful critique of our capitalist driven consumer culture. In an age where wealth is not merely acquired but flaunted through ‘conspicuous consumption’, as Thorstein Veblen described, the simplicity and self-sufficiency championed by Gandhi are drowned out by the noise of excess. The youth is also influenced by such a culture of commodity fetishism. We have seen spectacles of luxury in events like the Ambani wedding, which becomes grotesque in its vulgarity against the backdrop of extreme poverty and inequality. Gandhi’s idea of trusteeship – the belief that the rich should act as custodians for common good, is a challenge to this moral decay, and a powerful tool to hold those with power accountable for their responsibilities.

For the youth, the idea of engaging with Gandhi may seem irrelevant or unappealing. In our world of quick consumption, where political figures are “memefied”, Gandhi’s nuanced and often morally complex ideas struggle to find space.

Social media encourages us to engage with political figures through hyper-stylized, hyper-masculine “edits” and performative digital representations that favour spectacle over substance. In this landscape, the pile of Gandhi’s extensive writings (even ones that are directed specifically for students and the youth) lying somewhere in the library, seem distant, inaccessible, and unattainable.

But we must resist this urge to see Gandhi as monolithic, or try categorize him too neatly, or reject him entirely. His lifelong quest for truth was never static, he was constantly evolving, flowing, challenging even his own beliefs.

To engage with Gandhi today does not mean becoming a Gandhian. You can’t accept anyone in totality when you have your own critical faculty in place. Engaging with Gandhi today means embracing the courage to seek your truth, to question, to experiment, and to envision a better world rooted in compassion.

Gandhi had a vision for India. His vision, much like Euclid’s definition of a point, remains an abstraction – indivisible and seemingly unattainable. Yet, it is a horizon we must strive for and steer towards. In the pursuit itself, we may find the path to a more just and humane future.

Radha Sajanikar is a student of Sociology at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. She is passionate about writing on pertinent social issues.