Prejudiced perceptions about Puroik Children

‘Puroik bache ka soch alag hai; woh log absent mind wala hota hai,’ (Puroik children have a different way of thinking, they are absent-minded’). This was the response of the headmaster (HM) of Arunodaya Middle School, Seppa, Arunachal Pradesh, when we asked him if it was true that children from the Puroik Tribe have more learning difficulties than children from other tribes.

The HM belongs to the dominant Nyishi tribe to which, traditionally, the Puroik tribe (earlier known as ‘Sullung’, meaning ‘slave’) was bonded labour. ’ Throughout the interaction he kept describing various instances from his experiences that prove his claim. For instance, while education was perceived as an opportunity to achieve a better way of living by other communities, Puroik families either stop supporting their children or take back them from Seppa to their Basti (village), ‘çhidiyaghar,’ which the HM claimed to be a site of backward thinking. This is also why, he thinks, Puroik girls are made to marry at an early age while in other tribal communities such practices have become outdated. Furthermore, Puroik men were alleged to be drinking more and behaving indecently without ‘sharam-dharam’ (shame and responsibility) than men from other tribes. Despite the historical subordination and oppression faced by the Puroik community at the hands of Nyishi community, he blamed them for lacking a positive approach towards life and proudly asserted that his community has ‘given freedom’ to the Puroik community, yet they remain backward.

Arunodaya Model Village in Seppa

This interaction was part of our research study to explore trajectories of education, livelihood, and social mobility of the Puroik tribe in the East Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh. The study focuses on Puroik families residing in Arunodaya Model Village in Seppa, a resettlement colony constructed in the early 2000s. According to the National Human Rights Commission Report (2018), bonded labour was first reported by a Deputy Commissioner in East Kameng district in 1997. As a result, 3542 bonded labourers (about seven hundred families) were identified, out of whom, 2992 bonded labourers were rehabilitated under a district government scheme. The remaining people possibly migrated.

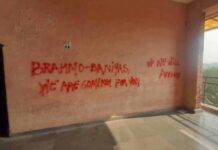

The East Kameng Chapter of All Puroik Welfare Society (APWS) selected thirty families based on certain criteria, such as their ability to speak Hindi and having at least one member who has completed IV standard, to settle in this model village. According to Puroik community members we spoke to, despite development interventions, they continue to live at the mercy of the Nyishis, especially in the rural areas. Even the families living in the model village had to face serious threats for a very long time from their old Nyishi masters.

Hierarchical Social Relations

The history of bonded labor relationship with Nyishi community has different versions of origin. One of the prevalent stories among Puroik community is that the Nyishi community were usually ones who settle down in the plain valleys and do agriculture. They started making requests to Puroik community for bringing different forest-based products such as Sago palm (a forest product, typically consumed as a staple food) and other house construction materials. They were also in need of laborers to work in their fields. In return Nyishi community was helping the Puroik community in different non-monetary ways. For instance, while a Puroik community member was marrying off his/her son the Nyishi community member was helping them by giving a Mithun (a semi-domesticated bovine species and is considered as a symbol of socio-cultural status in the area) as a bride price. Later this turned out to be a system wherein Nyishi community started claiming ownership over Puroik community. As a result of this system, Puroik community were systematically deprived of any rights to either live as per their wishes or own any means of capital including Mithun.

Out of thirty families that were rehabilitated in the model village, many sold the property within the community and went back to their villages. Many others left their children with relatives in Seppa and went back to their traditional livelihoods. Post the construction of the model village, there were hardly any efforts to improve their educational and livelihood status. The lack of a concrete development intervention both at the policy level and implementation level has resulted in persisting Puroik community’s dependence upon ‘Nyishi masters’ through generous paternalism in place of traditional outright slavery or forced bonded labor system.

Post Rehabilitation Experiences

Though freedom is offered to Puroik community legally, many traditional structures continue to hold power. Majority of the Puroik community still do not own land or have political representation. Only a handful from Puroik community have stable jobs such as low rung jobs in the government sector. While others find it difficult to find a livelihood source in Seppa hence they go back to their villages to traditional livelihood sources. Furthermore, for the purpose of resettlement, residents from Arunodaya Colony are selected from different villages in the district and hence they are not united on any front to fight collectively for their rights. Historically too, being a nomadic tribe, Puroik tribe is dispersed across different districts.

Lack of access to information, financial resources and social networks makes their educational opportunities in Seppa limited. Those who can access schooling face exclusionary practices, such as teachers using the Nyishi language for classroom interactions. Very few can afford to send their children to nearby cities, like Itanagar for higher education. Though the government has proposed various measures and schemes for the community, such as the promotion of SHGs, jobs in various state departments, effective monitoring strategy, posting of a designated Labour Officer and strengthening the Autonomous Puroik Welfare Board (APWB), there have been no significant concrete efforts to materialising these.

The only positive outcome that we noted was that in the schools that we visited in the Seppa circle, the percentage of Puroik children has increased in recent years though it is still minuscule when compared to that of the children of other tribes. While most schools had reasonable physical infrastructure, Arunodaya Middle School was in an extremely dilapidated condition. According to the HM, in the current academic year, there were only 20 Puroik students out of a total number of seventy-five students. He held the APWS responsible for not showing interest in the development of the school infrastructure.

The lived realities of the Puroik community raise questions about their inclusion and empowerment and the existence of slavery. It makes one question the long-term implications of rehabilitation interventions. To what extent can we consider one-time state interventions aimed at benefiting marginalized communities as markers of justice and democracy, given their deficiency in support structures and failure to address the prevailing, entrenched inequalities within socio-cultural, political, and economic realms?

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the organisation they represent.

The article has been authored by Vijitha Rajan, Faculty Member, School of Education, Azim Premji University and Aboobacker P K, Research Associate, School of Education, Azim Premji University.